Dance and art part 1: Expression and movement

September 18, 2020

For centuries, the movement, rhythm and beauty of dance has inspired artists. Symbolic and expressive qualities of dance have been conveyed in paint or pigment since prehistoric times.

These two articles look at some of the key ways in which dancers have inspired the creation of two dimensional artwork. In addition, I shall touch on how dancers have in turn been influenced by artists.

Conveying emotional expression

From quiet melancholy to wild abandon, the type of emotion communicated by dancers has long been a source of inspiration to artists.

Even before considering a figure’s facial expression or body posture, emotion can be conveyed on paper or canvas. The range of colours used, the degree of tonal contrast, the technical handling of lines or brush-strokes, and the relationship between the handling of background and figure can all influence the emotion conveyed by the image.

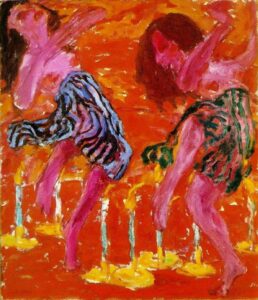

German Expressionist dance paintings of Emil Nolde (1867-1956) suggest at times a wild abandon or a sense of losing control. For example, see his “Candle Dancers”, above.

Though raised as a Protestant, old Germanic legends would have been a key part of Nolde’s upbringing (Jumeau-Lafond, 2008), and indeed some of his dance pictures suggest pagan ritual or demonic possession. Nolde is known to have been influenced by Mary Wigman (Byrne 2012), a pioneering modern German dancer who thought of dance primarily as a means of expressing internal emotional impulses.

The concept of “empathy” was originally closely linked to the way in which people viewed paintings. Robert Vischer, a German aesthetics student, wrote a dissertation in 1873 coining the term “Einfühlung”, literally translating to “feeling into” (Eisenberg 1990, p18). Einfühlung is the projection of people’s ideas, emotions or memories onto objects. The word Einfühlung later got translated into “empathy” in 1909 by the British psychologist Edward Titchener. Robert Vischer was also first to use the term “muscular empathy”: Due to Einfühlung, the viewer of a piece of art unconsciously “moves in and with the forms” (Henderson 2014, p115).

Of course, we also experience muscular empathy when watching dancers perform. The philosopher Theodor Lipps had a particular interest in both empathy and aesthetic enjoyment. Lipps wrote of how he experienced muscular empathy while watching a dance recital: he found himself to be “striving and performing” with the dancers (Lipps 1935, p379).

Representing different types of movement

Speed, direction and quality of the dancer’s movement can be suggested by the nature of repeated shapes and lines within an image. Such lines or shapes could be realistically-rendered folds of clothing, or may instead be bold individual brushstrokes or abstracted forms within the figure or background. Straight, geometric lines tend to suggest static held poses or, when repeated, jerky, start-stop movement. On the other hand, sweeping curves within an image are often used to suggest the effect of a more flowing type of movement.

For example, V.Pervunensky’s painting “In The Vortex of the Waltz”, above, contains many elongated, curved sided shapes that come to a point at one corner. Such shapes hint at the elegant lilting, rotating nature of the waltz. You’ll find these shapes forming zones of highlight or shadow within the white dress of the smiling female dancer, and they are echoed by numerous similar shapes throughout the picture: look at gaps between dancers’ limbs, and look at the shapes formed by white gloves crossing black jackets.

In “Dynamism of a Dancer”, above, we appear to see an arm in one place, and then in another and another. Through an effect similar to stop-motion, such repetition gives the impression of jerky or vibrating movement. Gino Severini was a member of the Futurist group of painters. In addition to celebrating the thrust of technology and the speed of modern life, one of the key visual aims of Futurism was to embody movement on two-dimensional canvas (Kissalgoff 1983).

A picture with regular or irregular repetition of similar shapes, tones or colours can suggest a rhythmic movement pattern. It achieves this by sending the viewer’s eye roving around the image making visual connections.

The chosen relationship between similar shapes within an image can hint at the dancer’s type of movement. Shapes may for example appear to tumble or cascade, suggesting that a dancer is doing likewise. Shapes that are distributed equally across the canvas will give a different effect to those that closely abut one another, or to those that are spaced apart at gradually increasing distance. In an image by another Futurist painter, Fernand Leger (1881-1955), “Exit of the Russian Ballet”, above, the dancers are repeated rounded volumes appearing to spin away from us.

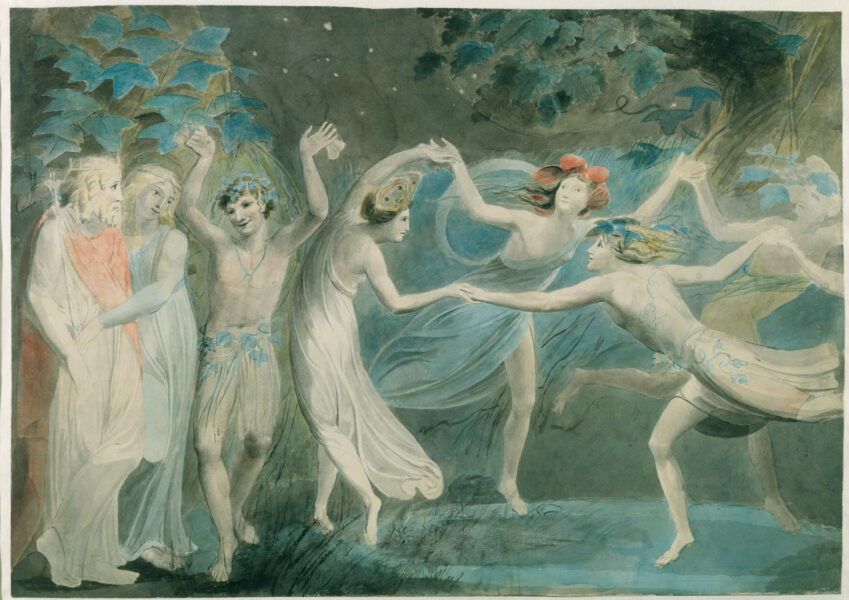

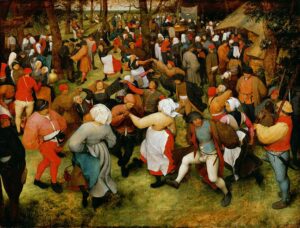

The use of repeated shapes, tones and colours to give the effect of rhythm and movement is not by any means limited to modern artists. For example, there is a clear sense of dance rhythm in “The Wedding Dance”, above. Brueghel (c.1525-1569) used strong tonal contrasts to emphasise the repetition of similarly shaped limbs across his canvas. The distribution of patches of each colour across the image also forms an abstract suggestion of rhythm. Look at the overall pattern created by red, or by white, within this wedding dance.

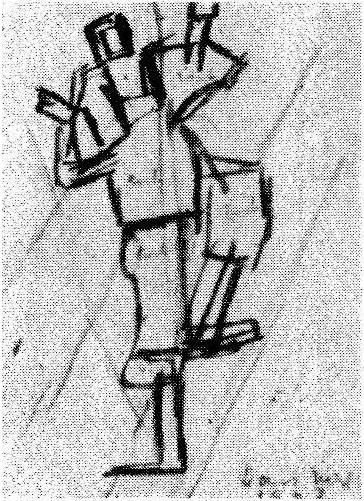

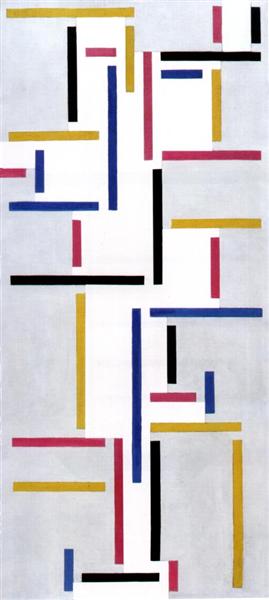

Following the principles of the De Stilj movement, also known as Neoplasticism, Theo van Doesburg (1883-1931) created a picture that is all about dance rhythm. The finished painting, below, uses only horizontal and vertical lines. It represents the rhythmic movement of a single dancer, but has also been compared to the appearance of dance notation (Kissalgoff 1983).

In a bravura display of painting, J.S.Sargent (1856-1925) created a portrait of the famous Flamenco dancer Carmen Dauset Moreno (1868-1910). In this image, below, Sargent not only fulfilled his commission in painting Moreno’s very recognisable face and figure, but he also gave the impression of her having stopped momentarily between dance steps rather than holding a static pose for him in the artist’s studio. The painter used arrays of shapes suggested by the folds of her dress to hint at the various types of movement within Flamenco dancing.

Linking expression and movement in art and dance

American dancer and choreographer Martha Graham (1894-1991) was greatly influenced by a painting by Wassily Kandinsky that she spotted in the window of an art gallery in the early 1920s. “In its most abstract form, it struck her as a brilliant streak of red against a field of blue. Looking at this canvas, she said to herself, ”I will dance like that.”” (Kissalgoff 1983). This experience is said to have inspired Graham’s creation of the 1948 work, “Diversion of Angels”.

Russian painter Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) not only influenced dancers, but was himself inspired by dance. He wrote of possible links between dance, colour, and the movement of abstract forms, and developed his own theories of how the colour of a shape affects how it appears to move within an abstract image. In his book, “Concerning the Spiritual in Art”, originally published in 1911, Kandinsky wrote that warm colours appear to advance towards the viewer while cool ones recede. A yellow circle appears to spread out from its centre, while a blue circle seems to move in upon itself like a snail retreating into its shell (Kandinsky 1977, p36-42).

Though primarily a painter, Kandinsky worked closely with dancers and musicians and made a major contribution to thinking about what form a dance of the future might take. One of his central goals was to create a dance that would deal with abstraction (Huxley 2017).

Hungarian dancer and choreographer Rudolf Von Laban (1879-1958) had remarkably similar ideas to Kandinsky regarding the relationships between abstract forms (Dörr 2008, p12).Interested in the space that surrounds the human form, Laban studied architecture at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris and went on to become a pioneering dance theorist. Laban the dancer and Kandinsky the painter both looked closely at how shapes could sweep together, tear apart and change in colour and size, the effect of dark and light, and spatial tensions between shapes and lines.

Some of Kandinsky’s ideas may have been influenced by the teachings of the empathy and aesthetics specialist, Theodore Lipps (see above under “Emotional expression”). Lipps ran a foundational aesthetics course at the University of Munich which was attended by, among others, Brancusi and Kandinsky. (Corbett 2018). Laban the dancer was also based in Munich for a period prior to World War 1, and would at that stage have come across painters from the Blaue Reiter group including Franz Mark and Kandinsky (Maletic 1928). That was certainly a fertile time of collaboration between painters, musicians and choreographers.

The idea for this blogpost was sparked by the recent creation of “Dance or Draw“. This is an opportunity to dance or to draw/paint dancers. It is run by Mel Simpson, with sessions open to new members and currently held online twice a month.

References

Byrne, B (2012) “Expression through Dance” Aesthetica Magazine, viewed online 10.09.20 at https://aestheticamagazine.com/danser-sa-vie/

Corbett, R. (2016). You must change your life: The story of Rainer Maria Rilke and Auguste Rodin. WW Norton & Company.

Dörr, E (2008) “Rudolf Laban: The Dancer of the Crystal”, Rowman & Littlefield

Eisenberg, Nancy 1990 Empathy and its Development: Cambridge University Press Archive

Henderson, James 2014 “Reconceptualizing Curriculum development” London: Routledge

Huxley, M. (2017). The Dance of the Future: Wassily Kandinsky’s Vision, 1908–1928. Dance Chronicle, 40(3), 259-286.

Jumeau-Lafond, J. 2008 “Emil Nolde 1867-1956” The Art Tribune 11 Nov 2008, viewed online 13.09.2000

Kandinsky, W (1977) “Concerning the Spiritual in Art”. Dover Publications inc.

Kisselgoff, A (1983) viewed online 09.09.20 at https://www.nytimes.com/1983/01/16/arts/dance-view-how-dance-and-other-arts-influence-each-other.html

Lipps, Theodor 1935 “Empathy, Inner Imitation and Sense-Feelings” Translated by Max Schertel and Melvin Rader. In A Modern Book of Esthetics: An Anthology. Edited by Melvin Rader. California: Holt, Rinehart and Winston

Maletic, V. (1928). Body-space-expression: The development of Rudolf Laban’s movement and dance concepts . Approaches to Semiotics Vol. 75. Walter de Gruyter & Co, Berlin.

Thank you so much for taking the time and effort to research and articulate through this exquisite blog Marianne. I feel so honoured to have inspired it’s creation!

It’s such a pleasure, Mel. Do keep the dance sessions running. They are always inspiring x