Shapes in art

April 30, 2014

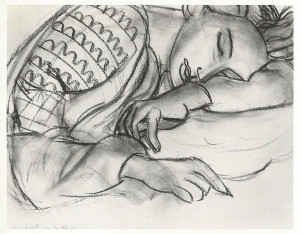

Mary Cassatt “The Long Gloves”, 1889

Whether we choose to produce figurative or abstract art, our drawings/paintings inevitably end up as a series of two-dimensional shapes on the page. Control shapes carefully, and this becomes exciting. Different shapes have the capacity to suggest specific emotions to the viewer, and even to hint at certain types of movement. Furthermore, a visual balance or echoing of shapes on the page can be intriguing.

Where are these shapes?

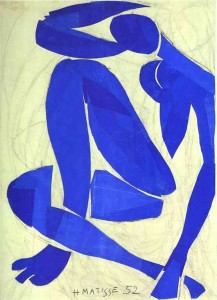

Above: Henri Matisse “The Sheaf” ,1953, paper cut-out

Abstract art, in some cases, is all about shape. Geometric or irregular “organic” shapes or forms may create the basis of the image (for example, see Matisse’s cut-out above)

But how can we achieve shapes in figurative art?

Seeing a whole object as one flat tone or silhouette is a quick way to achieve a clear shape: For a start, try viewing an object against a contrasting light or dark background. Backlit against a sunset, distant trees and buildings appear as simple shapes.

Indoors, try looking at backlit objects on your windowsill or look at people against the light for a similar effect:

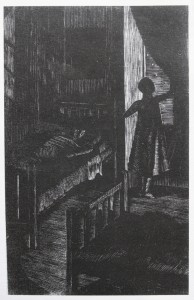

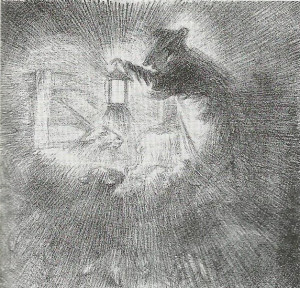

Above: Helen Binyon (1904-1979) “The starry night”, wood engraving. The girl forms a silhouette against the starlit window. Meanwhile, objects within the dimly-lit room are reduced to semi-abstract shapes.

A patch of contrasting colour may also form a prominent shape within your image. This may be, for example, a patch of yellow light across a landscape. Or it could be a brightly-coloured object such as a red cup on a table.

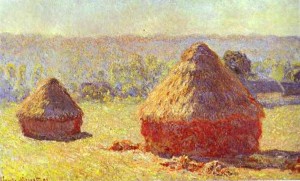

Above: Claude Monet “Pathway in Monet’s garden at Giverny”, 1900, oils. Patches of bright sunlight form peachy-coloured shapes across the path between the dark, mauve-tinged shadows. Notice how the shapes of contrasting colour and tone repeat along the path and draw the viewer’s eye into the picture.

If you use a linear drawing technique, then you may find that your lines appear to enclose shapes . For example, see the strongly-outlined arms of Mary Cassatt’s “The Long Gloves” reproduced at the top of this article. Notice how these arms each form a boomerang-like shape, and how these shapes appear to echo one another.

By using shapes of shadow or high tone within your image, we can add interest to the composition while retaining the illusion of three-dimensional reality:

Above: Edgar Degas “Portrait of Giovana Bellelli”, 1858-9, pencil. Look at the patch of light tone on the girl’s right cheek, shaped like an inverted comma. Shapes of light and dark tone throughout this image are round-edged and asymmetric, increasing the lyrical, tender effect of this portrait.

Above: Edgar Degas “Portrait of Giovana Bellelli”, 1858-9, pencil. Look at the patch of light tone on the girl’s right cheek, shaped like an inverted comma. Shapes of light and dark tone throughout this image are round-edged and asymmetric, increasing the lyrical, tender effect of this portrait.

Intriguing “negative” shapes can also be seen between objects:

Above: Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, “Messaline”, oil on canvas, 1900-1901, 92.5x68cm. The red background forms prominent shapes between the figures and is very much part of the picture.

In my next article, I’ll suggest ways in which different types of shape can be used to suggest emotion in your pictures…

| Tags: composition, negative shapes, shapes

What can artists learn from scientists?

March 5, 2014

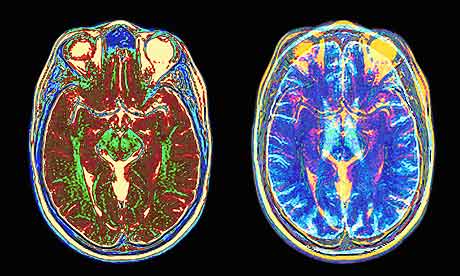

Images of the human head as recorded by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI scan)

Is it a good idea to use scientific ideas in your artwork?

Yes, perhaps, but watch out:

- I’d recommend fully immersing yourself in a subject before commenting on it artistically. Reference to a misunderstood scientific concept risks embarrassment, so do read around the subject and, if possible, get to know some experts in the field.

- Much that is published in the media as scientific “fact” is only applicable in certain contexts, or in some cases may even be flawed. Aim to speak to a variety of people in the know before coming up with your own opinion.

How about borrowing scientific imaging tools?

In opening up fresh opportunities for observation, scientific imaging can be inspirational to the artist. Microscopy, radiography (X-ray images), cineradiography (moving X-ray images), thermal imaging and slow-motion video analysis give us new insights into our world.

Some medical and scientific images are curiously ambiguous, being both beautiful in an abstract sense, and carrying specific meaning to those trained to understand them. For example, groups of cells seen through a microscope form striking patterns accentuated by first staining the sample on the microscope slide. Cross-sectional images of the body achieved by MRI or CT scanning often contain compelling shapes and can be curiously symmetrical.

As artists, we often look for visual patterns and trends while also seeking meaning. Be inspired by a current art-science exhibition on this very subject: “Beautiful Science: Picturing Data, Inspiring Insight” , is on display at the British Library until 26 May 2014.

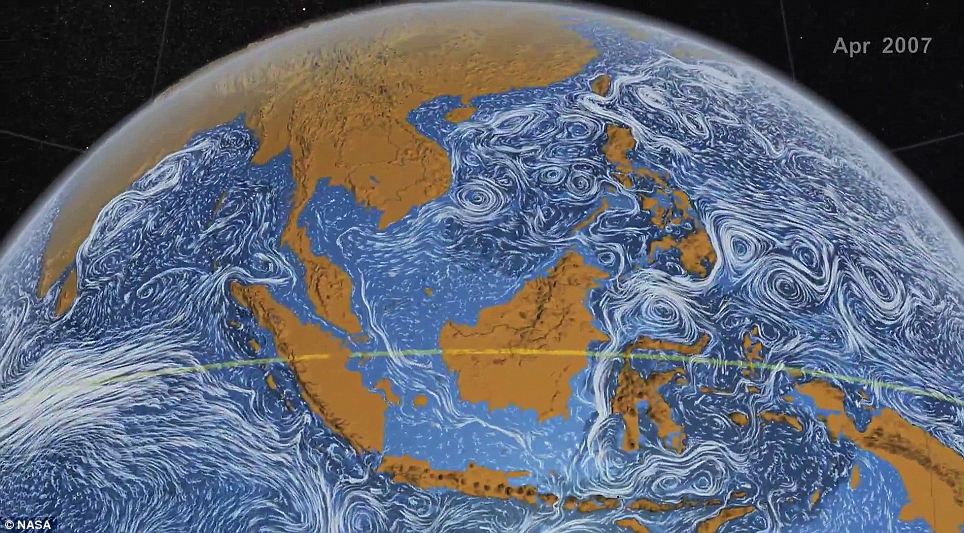

Above: Visualisation of ocean surface currents by NASA

“Scientific thinking” for artists: Some practical tips

Here follows a long list of suggestions. Different methods work for different artists, so just pick out anything that strikes you as useful.

Getting to grips with a practical problem

Freedom of expression and spontaneity are valued highly by many artists. Nevertheless, there are times in most artists’ lives when a lack of control of the medium hinders creativity. Established protocols for paint-mixing, etc., are no longer taught in many art schools, perhaps in order to leave students more potential for creative expression. How can an artist develop his or her own technical skill?

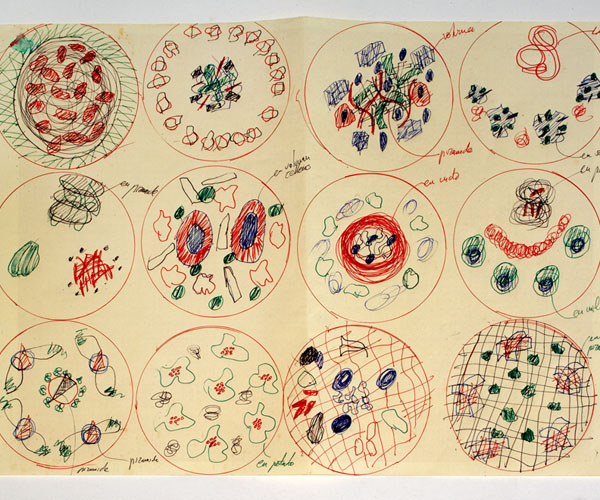

Trying things out (“trial and error”) can be very useful to the developing artist. If this seems like a frustrating business then go about it in systematic way and take the opportunity to record results. For example, keep a notepad by your easel and make a note of paint mix colours that work for you. Record what doesn’t work too. Learn from the example of the great creative chef Ferran Adrià, who is said to have rigorously recorded culinary creations that were successful but, just as importantly, recorded all unsuccessful food combinations.

Above: Ferran Adrià plating diagram, ink on paper. This great creative chef draws potential culinary ideas but also has a great system of recording results of food experiments as written notes. He said, “I always have a pencil with me, to the point where it forms a part of me. I write a lot during the day”

If you really want to get to grips with a practical problem then test it rigorously. First decide what you are testing. So, for example, you might be testing the suitability of different types of paper for use with inks. In this example, a few specific types of ink mark would be made on each type of paper. Of course, brand of ink, style of brush-stroke or pen-mark and quantity of water added to the ink would all affect the finished result, so these must not vary. Label each variety of paper, and either store the results in a plastic wallet file for future reference, or make a clear written note of the outcome.

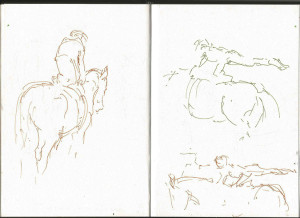

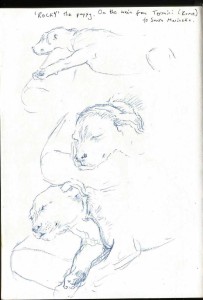

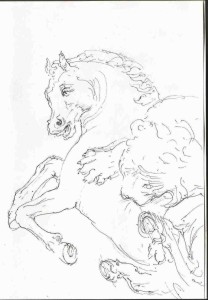

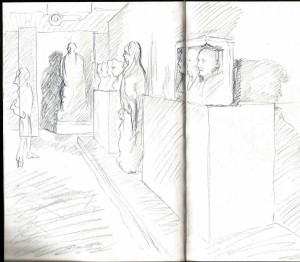

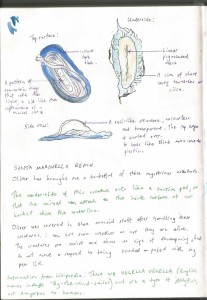

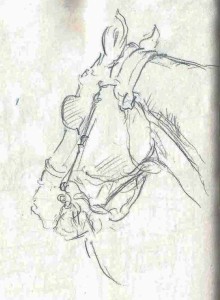

Scientists are trained to focus on just one problem at a time, but this skill is also useful to artists. Do you ever find yourself completely overwhelmed and unsure of where to start, perhaps when drawing or painting an unfamiliar subject? In some cases, this sense of helplessness (“I can’t draw that“) is simply due to attempting to solve too many problems at once. Each new artistic subject presents a whole set of challenges or conundrums. For example, drawing horses from life can feel overwhelming to those who have never tried it before. Equestrian drawing involves all kinds of challenges including unfamiliar proportions, foreshortening, tones, colours, movement and textures. A positive approach is to make a series of drawings, each focused on a single area of concern, e.g. one drawing to investigate tones, another looking closely at 3D structure, etc.

Some finished pictures do focus on just one aspect of their subject and this can, at times, make the work more interesting and compelling. If, on the other hand, you wish to perfect several aspects of your subject in a finished picture, then you will need to solve multiple problems. For example, the colour of fur in sun and shadow is one “problem” while the way in which to make the animal look as if it is leaping is another. Before tackling your finished picture, investigate each problem individually by making preliminary studies, colour trials and perhaps also by observing the work of other artists.

Above: Rosa Bonheur “The Horse Fair” 1853-1855, oil on canvas. The creation of this complex image required great problem-solving skills: animal behaviours and movement, the effect of light and shade on each coat colour and the shapes within and between moving horses all needed to be understood. Rather than being overwhelmed by the task, Bonheur solved each problem in turn. She is known to have visited slaughterhouses to study anatomy, and to have observed horse fairs in action (she attended dressed as a man) where she made preparatory drawings.

Building upon what others have discovered

Scientists refer clearly to the discoveries of others when presenting their work. Every respected scientific paper contains a list of such references.

In attempting to create original artwork, don’t be ashamed to study the work of other artists. Do learn from and build upon what others have already discovered: Look with curiosity at the work of great artists – how have they problem-solved? This process can eventually help direct you on your own original creative path.

Careful measuring

If you choose to use measuring techniques in drawing and painting, then they must be used carefully and correctly. Not everyone “gets on with” measuring – some artists focus more on replicating observed shapes (perhaps a more intuitive way of working). That is fine – use whichever technique works best for you.

Measuring (i.e. establishing proportions by holding a pencil in your outstretched arm and measuring off distances) can be incredibly useful but, as it side-steps intuition, this technique risks grave error if it is done badly. In the headlong rush to be creative, holding the pencil skew, having your arm bent, and rushing the measurement can all introduce mistakes. If you choose a measuring technique then have your chosen method clear in your mind, be consistent with it, and be prepared to question and repeat your own measurements.

Perhaps those who like to use measuring techniques are particularly adept at flitting between logical and intuitive way of thinking during their work.

An investigative approach

Fundamental to both art and science is the on-going desire to ask questions and solve problems. This is what keeps an artist’s work interesting. However, it can be tempting to take the easy path of producing images that say the same thing over and again. This might appear to make sense commercially but, in the long run, is it art?

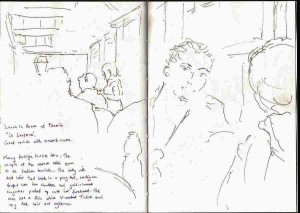

If you’re interested in something, then watch out for it wherever you go and in all conditions. Sketchbooks are useful here. E.g. shadows on human heads(where do they fall, how dark are they, what colour are they?)=> keep looking at people of all types and in different lighting conditions, and keep recording.

Above: Antoine Watteau was fascinated by the structure and character of human heads. He left numerous sheets of studies such as this and take trouble to seek out models of various ages and ethnic backgrounds in making such drawings

Do take note of interesting things and anomalies.

Be sure to stop, observe and think before and in-between drawing/painting.

Consider an investigative approach in which you try out different ways of looking at the subject and different options for image-making. Take the example of looking at a figure in a life drawing setting. Part of the model may look as if it is really bearing a lot of weight- what gives it that appearance? If this interests you then don’t be afraid to investigate: Look from different directions; ask the model to shift weight off that area and then load it again and observe carefully –change the lighting and look again– shadows, angles, shapes- what changes?

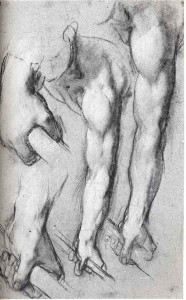

Above: Federico Barocci study of arms and hands in charcoal and chalk. Here, Barocci used investigative drawing to discover how to portray a man’s arm holding a stick. Between drawings, he must have asked his model to move the arm and grasp the stick again in a slightly different way. Observation of real movement in context can be far more valuable than studying still photographs of posed models.

Has this series of articles on art and science given you food for thought? Feel free to add your opinions by clicking here.

Current and upcoming exhibitions exploring art and science

“Discoveries: Art, Science and Imagination from the University of Cambridge Museums” runs at Two Temple Place, Cambridge, until 27 April

Christopher Benton-Art and Science : mixed media works by a clinical and research MRI radiographer. At Hertford Theatre 6-29 March 2014

Courtyard Arts: Art and Science: Selected from submissions on the theme of art and science. Runs until 29 March 2014 at this Hertford gallery

“Beautiful Science: Picturing Data, Inspiring Insight” runs at the British Library until 26 May 2014

The Art.Science.Gallery in Austin, Texas: Microscopy-inspired work by Katey Berry Furgason is on view until March 23 2014. Watch out for future art-science fusion exhibitions at this specialist gallery.

What can scientists learn from artists?

January 26, 2014

In comparing approaches to art and science, I notice that certain shared skills tend to be better taught to artists while others are addressed more clearly in science lessons. Let’s look, today, at aspects of the artistic approach that some scientists may find helpful. My intention here is not to be unfairly critical, but to trigger positive discussion.

If you are an artist, then do read on because these ideas may set you thinking.

If you are a scientist, then you may or may not find this list helpful. Perhaps you are already using these techniques, see no practical place for them, or disagree with some of my assumptions? On the other hand, if you feel lacking in direction or otherwise “stuck”, then this article could perhaps be useful to you. Please read on and feel free to add your own thoughts in the comments box at the end.

.

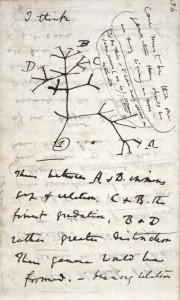

Above: A page from the notebooks of Charles Darwin, 1837-8

Observing and recording all that is interesting

The ability to observe and consider everything around you…looking, listening (and smelling, tasting, or whatever is appropriate), is key to scientific enquiry. While techniques of methodical observation are taught in science classes, a delight in a general awareness of our surroundings is , in my experience, encouraged more in art than science departments.

Art students are sent out with sketchbooks and encouraged to make observations, drawings and notes. The same approach with portable blank book and pen could be just as practical for the curious scientist. As with an artist’s sketchbook:

- you can take the book anywhere, from airport to park

- anything can be included, whether words, numbers or simple sketches (even if you feel that you “can’t draw”, it is fine to record visual or conceptual ideas using directional lines and simple shapes).

- an ideas book can be used to record what you see and what you think

- many of the ideas will probably come to nothing, while the occasional page may contain seeds of a new line of enquiry. Keep old completed books even if they seem to be full of hopeless scribble as, in years to come, you may look back through them with greater insight.

Above: Leonardo da Vinci. Notebook studies of both a seated figure and of turbulent flow. Note the association of flowing robes and turbulence images. The continuous format of a notebook or sketchbook encourages a sequence of interesting ideas. It is of course also possible to create an imaginative ideas book without being a master draughtsman.

Being ready to seek inspiration from anywhere

Young artists are encouraged to seek something interesting from the most mundane situations. They might be expected to look afresh at a single piece of drapery, the surface of a puddle or the corner of a room and then create an original image.

Should scientists take, at times, a similar approach?

The great physicist, Richard Feynman, said:

“I don’t know anything, but I do know that everything is interesting if you go into it deeply enough”.

Above: Eugene Delacroix “A corner of the studio” 1830, oil on canvas

Learning from your own emotional responses

Good art teachers remind students to be aware of their own emotional response to each object or situation. On the other hand, scientists are expected to be highly-objective in recording what they see and emotional involvement is therefore often discouraged.

Of course, objectivity is essential at certain times, e.g. when recording sets of values. However, there are occasions when an emotional response can help to direct you to initial observations that are surprising, and hence to those that may warrant further investigation.

For example, in studying canine movement recently, I came across this video of a galloping greyhound:

I set about looking at the video to record objective data for an assignment (limb step sequence, etc.)

However, the first thing that struck me about this was the rather alarming, even frightening appearance of the running dog. I asked myself what could be giving this dog such a “scary” look when running – he appears perfectly benign at the end of the video when resting on the grass. I concluded that the alarming appearance resulted from the dog’s dramatic up/down head movements with mouth gaping, teeth exposed and whites of eyes becoming visible at each head rise. (Indeed, if I cover his head, he no longer looks scary to me). What was initially an emotional response to the video could send me along several fresh lines of enquiry….”Why does the greyhound move his head up and down more than the cheetah?”; ” Is the mouth opening passively as he raises the head, or is this a sharp intake of breath” (“is breathing coordinated with running and, if so, how?”) “The downward roll of the eyes appears to be part of a set of known reflexes caused by changing neck position but I’d not noticed it before in a galloping animal…is eye movement always so extreme in running dogs…and other species?” And even, changing the subject somewhat, “do most people tend to see flashing whites of eyes as menacing?”

Don’t worry…I did also remember to record the objective data as originally planned.

A positive use of subjective language

When making sets of observations, scientists need to work systematically and objectively and record measurements in standard units.

However, additional subjective observation can provide a wealth of extra information, and having a meaningful descriptive vocabulary at your fingertips can be useful. For example, you may observe something as “lurching”, “bulging”, “swinging” or “sagging”, or hear it go “crunch”, “slosh” or “pop”. These are all unscientific words, but each may have a specific meaning to you. Use of such words can help both in understanding what is happening in a general sense, communicating with others (especially lay-people) and in directing future objective analysis.

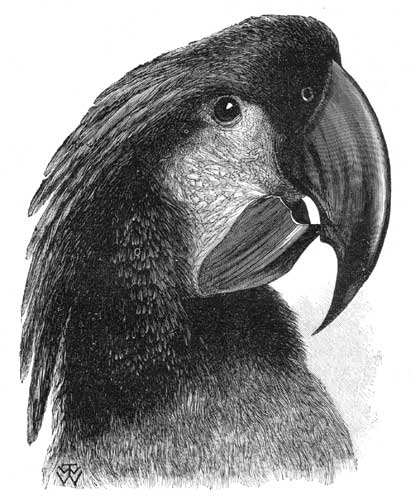

Above: “Head of a Black Cockatoo” engraved by T.W.Wood. From The Malay Archipelago by Alfred Russel Wallace

The naturalist and explorer, A.R.Wallace, came to original conclusions about natural selection from his observations. His diaries and notes include much colourful description backed up with objective data. An example of his subjective writing describes the bird pictured above:

“This cockatoo is the first I have seen, and is a great prize. It has a rather small and weak body, long weak legs, large wings, and an enormously developed head, ornamented with a magnificent crest, and armed with a sharp-pointed hoofed bill of immense size and strength…”

The cockatoo’s remarkably strong head and beak and surprising plumage turn out to be specific evolutionary adaptations. Wallace’s subjective approach was key to his understanding of relationships between species and their environment. Of course, he recorded numerous measurements and other objective data along the way.

An artist’s approach to combining subjective and objective description:

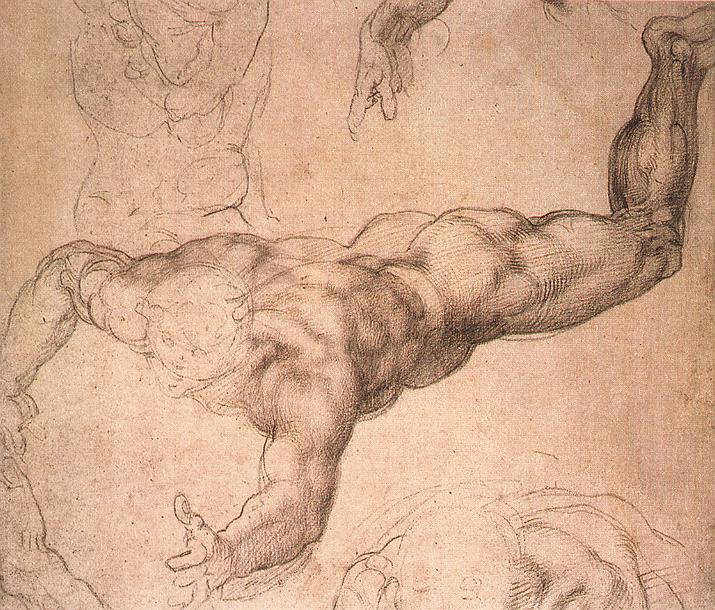

Above: A sketch for the Sistine Chapel by Michelangelo. This image includes clear rendering of muscles of the limbs and trunk. However, this drawing is primarily about the process of “reaching out forward”, and its gestural quality tells us more about the body than we can glean from dry anatomy texts.

Use of analogies and metaphors

Some phenomena are so strange or unexpected that it is difficult to understand their implications without relating them to what we already know well.

Analogies are used by good science teachers (click here for an online resource on teaching with analogies). A beautiful example enables us to “get our heads around” the massive scale of our solar system. Astronomical figures initially seem meaningless, but a model using familiar objects helps us to understand and engage with the huge distances. In the Thousand-Yard Model, familiar objects represent each planet, so the Earth is a peppercorn, Jupiter a chestnut, etc. The Sun is a bowling ball. These objects are taken outside and placed at specific distances from one another to represent their relative spacing in the solar system. The resulting model solar system is a thousand yards across and is quite awe-inspiring. Full instructions on pacing out the Thousand Yard Model are provided by Guy Ottewell and can be accessed by clicking here.

But are there other areas of science where analogies are under-used? Imaginative comparison is key to the visual arts and of course to poetry. But does an emphasis on objective reasoning leave some scientists without these useful tools?

The confidence to pursue whatever fascinates you

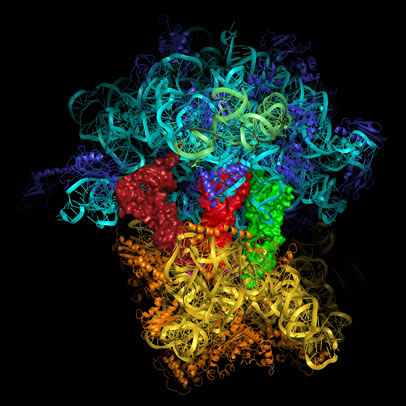

Above: The structure of a ribosome, an essential component of all living cells.

While artists are often encouraged to follow their interests and passions, young scientists perhaps more easily find themselves following lines of enquiry dictated by perceived need, available funding or, at a school level, by a specific syllabus. Is this a cause for concern?

When asked by the Observer, “What words of advice would you give to a teenager who wants to pursue a career in science?“, Venkatraman Ramakrishnan, who shared the 2009 Nobel prize for chemistry for studies of the structure and function of the ribosome said,

“Find out what really fascinates you and follow that. Almost anything in nature, if you follow it, you will find a scientific problem.”

Error: Contact form not found.

| Tags: art and science, blog, Leonardo

Art vs. science: a closer look

January 9, 2014

Following on from my previous article, let’s now look more closely at the approaches of scientists and artists. Can they really have much in common? I’ll start by outlining scientific procedure, and then see how the artistic process compares.

Scientific procedure

Oxford English Dictionary definition of “scientific”: “a method or procedure that has characterized natural science since the 17th century, consisting in systematic observation, measurement, and experiment, and the formulation, testing, and modification of hypotheses.”

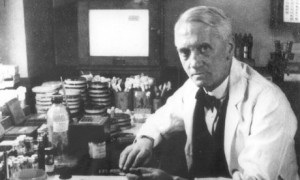

Above: Alexander Fleming in his lab, surrounded by petri dishes, etc.

Observation:

Many lines of scientific enquiry (especially novel, ground-breaking ones) start with an interesting observation. This is a process of “noticing something curious” and does not necessarily occur under controlled laboratory conditions.

For example, in 1928, Alexander Fleming noticed something odd about an open petri dish in his lab. This was a petri dish known to contain bacteria. What struck Fleming as interesting was a mysterious ring without bacteria on this dish. And surrounded by this bacteria-free halo was a growth of mould.

Admittedly, not every single scientific investigation starts with an observation. Some may begin with a need to solve a problem. Consider the many scientific trials involved in producing a medical drug these days. But even when using more of a problem-solving approach, the scientific process of observing and thinking at each stage of the development of the drug is essential.

Note that The “systematic observation” included in the OED definition usually comes later, at the testing stage of the process.

Coming up with a question:

Every line of scientific investigation involves a question. E.g. “Why does this happen?”, “How does that work?”, “Does that treatment work?”, “Why was that set of results not as expected?”, etc., etc.

Fleming’s question would have been something like, “why is bacteria not growing around the mould?”

Curious, he sampled and cultured the mould and identified it as a species of Penicillium.

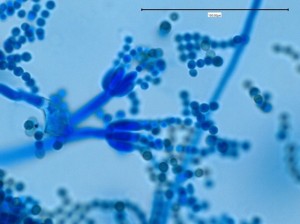

Above: a species of Penicillium as seen through a microscope

Making a hypothesis:

Using any information to hand, the scientist comes up with a hypothesis, i.e. a suggested answer to their question. In many cases, the hypothesis is simply an educated guess.

An initial hypothesis in the above example might have been, “This Penicillium mould inhibits bacterial growth”. (This turns out to be exciting, as the story eventually leads to the creation of the antibiotic, Penicillin).

Testing:

Any hypothesis needs rigorous testing.

Following initial observations, it would be necessary to conduct an experiment using multiple agar plates seeded with a known type of bacteria. A pure growth of the Penicillium mould would be seeded onto just half of the plates. We’d predict that bacterial growth would be inhibited only on the plates containing the mould. Lids are kept on this time, as we need to know whether any inhibition of bacterial growth is due to the mould or instead merely due to some other environmental contaminant. Temperature and other conditions are strictly controlled, and careful, systematic observations made and recorded.

Results are then analysed,

and a decision is made as to whether the hypothesis is valid.

These days, each scientific discovery must be presented as a paper (there are close guidelines as to how this should be written), and this piece of writing must then go through peer-review (expert criticism) before publication.

A response to the results:

The results of the initial experiment may set the scientific community wondering about further possibilities…

E.g. “I wonder if the Penicillium inhibits all species of bacteria on agar plates” or, eventually, “I wonder if the Penicillium would work in the human body to cure bacterial disease”. Each new thought leads to a fresh hypothesis that then requires rigorous testing.

Above: The life-saving drug, Penicillin, was developed from Penicillium mould in 1939 by Dr Howard Florey and his colleagues at Oxford University.

I have chosen the well-known story of Fleming’s discovery of Penicillin because of its emphasis on “noticing something” and “coming up with a question”. On further reading I have just found that, coincidentally or not, Fleming was also an amateur artist, a member of the Chelsea art society and is even believed to have drawn with bacteria!

How does artistic procedure compare with the above?

Observation/ Noticing things

Scientists may start their investigation by noticing curious phenomena in the real world or unexpected results from previous experiments.

But what do artists notice?

Anything in the real world that makes us “look twice” or leads us to think, “that’s interesting/ strange/ unexpected”, is a good starting-point for creating a piece of artwork. Artists are good at noticing something curious even in the most mundane situations (click here for further thoughts on this).

In figurative art, there is a particularly strong tradition of noticing:

Effects of the light

Human posture, how we move and how we spread our weight (think of all that closely-observed life-drawing)

Body language, facial expression and the minutiae of social interaction

But artists also notice their own emotional response to what they see and experience (including their response to news stories or even to fictional narrative), and this particular emotional response can be the basis of the resulting artwork.

Artists are great at noticing their own emotional response to colours, shapes, directional lines and movement, whether in the real world or within a picture, sculpture or film.

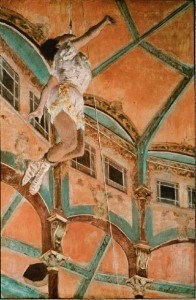

As an example, let’s take Edgar Degas and his creation of the painting, “Miss La La at the Cirque Fernando”. I’m choosing this because Degas is known to have gone through quite a struggle to create it, and several studies exist relating to different stages of the process.

Above: Edgar Degas “Miss La La at the Cirque Fernando”, oil on canvas

Miss La La was an incredibly strong, agile and brave performer who worked at the Cirque Fernando close to where Degas lived. Why did Degas choose to paint this image? What struck him as “interesting” or “incredible” about this scene? He is not here to tell us, but we know that he was fascinated by human movement, the structure of the female form and unusual juxtapositions of figures against their surroundings. He appears to have noticed the following, and then set out to include them in his final image:

Miss La La’s unique pose, which is a unique combination of passive hanging plus strong arms ready to control the spin of the rope

The amazing height that she’s achieved, far above the crowd

The shape of her against the architecture

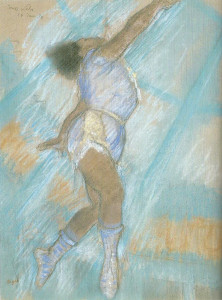

Above: Edgar Degas : One of many preparatory drawings for Miss La La at the Cirque Fernando, 1879, pastel and pencil on paper, 46x30cm

Coming up with a question

Admittedly, questioning is a subconscious process for many artists, though I believe that it is an important part of working creatively.

In response to noticing something (see above), the artist comes up with a question. For those who draw and paint, this question can be rephrased as a practical one. Here are some examples of specific questions that artists might ask themselves:

In embarking on a self-portrait: “What is it about me that makes me recognisable as “me”?”

and then: “how can I draw myself so that the resulting self-portrait looks like me?”

In drawing people at work: “How do these people move? How do they interact with each other?”

and then: “how can I capture the movement of these people in my drawing?”

In drawing a still life, the question might be: “Why does this vase of flowers make me feel joyful?”

and then: “how can I convey this sense of joy in my painting of the flowers?”

Note that the artist may need to ask and answer several questions before creating a complex image such as “Miss La La…”.

Degas made separate preparatory studies relating to the figure and the architecture for this image. It is said that he struggled to resolve the shapes of the architecture, possibly even hiring professional help to get this right (D.Sutton, “Edgar Degas, Life and Work, NY1986). But let’s look at the issue of the figure hanging from the rope. What question might Degas have asked himself?

“Hanging from the rope, why does Miss La La look both passive and strong?” or he might have asked , “How is she managing to hang from the rope without spinning out of control?”

For the painter, either of these questions leads onto a practical drawing/painting question:

“How can I paint Miss La La hanging from that rope so that she looks both passive and strong?” or perhaps, “How can I draw/paint Miss La La so that she appears to be hanging, and yet perfectly controlling the rope spin?”

Degas was experienced at painting dancers and athletes on the ground, but this was a new problem for him…

A thought similar to a hypothesis

Unlike scientists, artists are not expected to write a formal hypothesis! But the thought process can nevertheless be similar.

Back to Degas and Miss La La:

Degas might have thought, “I reckon that if I draw Miss La La with her upright body position, relaxed bent knees, feet pressed against each other and strong, out-stretched arms, then she will look convincing as someone who is passively hanging but yet controlling the spin of the rope”

Testing

There are exceptions but, unlike scientists, artists do not tend to put their ideas through a rigorous, controlled test process. This is one big difference between the process of art and science.

Preparatory studies and sketches are, however, a form of testing.

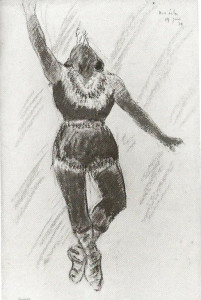

Above: Degas, an early study of Miss La La (drawn with upright body position, relaxed bent knees, feet pressed against each other and strong, out-stretched arms), Black crayon 45.6x24cm, 1879

Above: Degas, an early study of Miss La La (drawn with upright body position, relaxed bent knees, feet pressed against each other and strong, out-stretched arms), Black crayon 45.6x24cm, 1879

An early study for the painting of Miss La La (shown above) has her facing the viewer. It is a powerful image but, in my opinion (and Degas’ too, as he rejected this viewpoint), it fails to show the spin-controlling power of the woman’s shoulders and arms. (Additionally, this viewpoint fails to show how high she is above the crowd).

What next?

Degas’ next “hypothesis” was that he could perhaps achieve the controlled dangling effect if he clarified the position of the woman’s arms. Those arms would have a big effect on her speed and direction of spin beneath the rope.

He proceeded to test this by drawing her with the raised arm thrust forward and the lowered arm behind her back. The arms are also rotated (look at the positions of the hands):

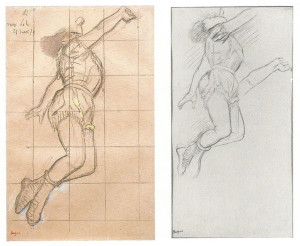

Above: Edgar Degas, two further preparatory studies for “Miss La La at the Cirque Fernando”, 1879

Above: Edgar Degas, two further preparatory studies for “Miss La La at the Cirque Fernando”, 1879

Analysing the results of the test

A good scientific study produces a set of objective results. Using statistical techniques, these results are analysed before the scientist can conclude anything from the study.

This varies tremendously from the artist’s approach. Artists do, however, evaluate their own work, even if just to say, “Yes, that produces the desired effect”. Though highly subjective, this evaluation process can be useful if applied to sketches or first drafts. Think of each sketch as testing something, and each evaluation process as assessing the result.

Above: Yet another study by Degas for the painting of Miss La La. Pastel, 61×47.5cm, 1879. This is very similar in structure to the squared-up image higher up the page, but this drawing also tests out colour ideas and the positioning of the rope end in her mouth. Notice how Degas squared this image up for future use though the figure then underwent yet more slight changes. Developing a piece of work through a series of preparatory studies can be a lengthy business.

A response to the results

Like scientists, good artists look at their own work, and that of others, and come up with further ideas. This may be a personal response to a masterpiece seen in a gallery, or a response to their own work.

It is particularly your own “failed” pieces of work that can generate useful new ideas. Notice Degas’ useful response to his early drawing of Miss La La shown face-on. He wasn’t happy with it, but worked out what to change.

Summary

“Noticing something interesting” is a key process for artists but is also important in making scientific discovery.

Both artists and scientists should be asking questions.

Coming up with a suggested answer to the question is useful for both artists and scientists. Scientists make a hypothesis. Some artists may find it helpful to think in a similar way.

Scientists test things in a very controlled, rigorous way. Artists also test things, but not necessarily in such a controlled manner.

Both scientists and artists respond to the outcome of their work in a positive way, and this may be a fresh starting-point for a new line of investigation or piece of work.

Error: Contact form not found.

| Tags: art and science, Degas

Art and science: Is there any overlap?

December 16, 2013

Above: Joseph Wright of Derby “An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump”, 1768, oil on canvas

I’m currently furthering my veterinary knowledge in order to specialise in small animal rehabilitation. In addition to fantastic practical sessions, this course has sent me back to the dissection lab, and to the library in search of scientific papers.

With a life split into distinct sections (drawing/painting, scientific study and on-going part-time veterinary work) I started to say, with a smile, “I’ll just put my art hat on” when about to start drawing or, “hang on, I’ll just put my learning hat on” before focusing on the veterinary course.

And then one day when I forgot to take off my “art hat”, I noticed something interesting: My grasp of new scientific ideas seemed more complete, and more satisfying, if I continued to think in an artistic frame of mind.

Why should this be?

Can something of the artistic approach be valuable to the scientist?

Indeed, can something of the scientific approach be of value to the artist?

With current interest in interdisciplinary thinking in the art world (click here, for example, to see details of the new MA in Art and Science run by the University of the Arts, London) these questions deserve more thought.

A very general comparison of the scientific method with the artistic approach

I’ll explain and illustrate these points more fully in my next article but, as an introduction, here is an overview:

What do scientists do?

Scientists notice things (they may note an interesting observation from the natural world, or else a point worthy of investigation resulting from a previous scientific study)

Scientists come up with a question and then a hypothesis.

Scientists perform an experiment or trial in order to test their hypothesis. This testing procedure is very methodical and can, in some cases, be time-consuming and repetitive. Results are recorded carefully.

Scientists analyse their results objectively and come to conclusions.

Scientists present their results and conclusions for others to share (there is a peer-review process prior to publication).

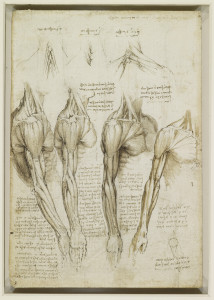

Above: Leonardo da Vinci: “The superficial muscles of the upper extremity from the lateral to the anterior aspect in turning through a right angle”, c. 1510. Leonardo was investigating superficial anatomy as required for artistic representation of the human shoulder. He wrote questions to himself in the text: “What are the muscles which are never hidden either by corpulence or by fleshiness? What are the muscles which are united in men of great strength? What are the muscles which are divided in lean men?”

What about artists? What do artists do?

The artist’s way of going about things is less well-defined, but perhaps has more in common with true scientific methodology than we might have at first thought:

There are of course a great range of artists working in any kind of medium from pencil to video installation, and with approaches that vary tremendously from one another. What do all these people have in common?

Artists notice things (a view shared by Grayson Perry and others)

Artists question and, if necessary, rethink accepted ideas.

Artists present their thoughts for others to share.

The above three sentences sum up what artists do (if you’d like to change my wording, disagree or add to this, then please share your thoughts in the “comments” box, below). These three tasks (noticing, questioning and presentation), are also fundamental to good science.

Do artists perform tests or experiments? Yes, to some extent, but very informally and in a subjective manner. Many artists solve problems through a process of trial and error. This is a kind of valid but unsystematic testing. There are also ways of thinking through an artistic question or problem and working out a solution by making and evaluating a series of preliminary sketches.

Do artists analyse their results? Yes, but this is an extremely subjective evaluation. It may be a matter of self-evaluation, or involve the difficult business of presenting finished work for critique, competition or sale and noticing what other people say about it.

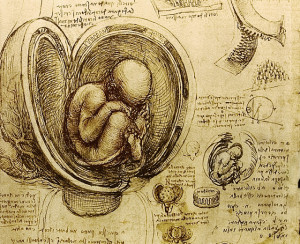

Above: Leonardo da Vinci “The foetus in utero”, c.1510-12. There are actually some errors here in the representation of the anatomical coverings of the human foetus and, in the text, there is the incorrect statement that the heart of this child does not beat. However, this image is remarkable in its empathy. Leonardo drew from (presumably rotting) corpses, yet he shows the foetus as a precious child huddled within its mother. This is entirely relevant to his accompanying text in which he writes about the shared soul of mother and child. Within this text he writes, “…the desires, fears and pains are common to this creature….and a sudden fright kills both mother and child”.

Some other comparisons between artists and scientists

In both art and science, there is a fantastic culture of learning from what others have previously achieved. Artists continually look at old paintings and contemporary work to see how both their peers and the “great masters” solved familiar problems of technique, composition and representation. Scientists read around their subjects of interest, learning from the previous work of others and keeping abreast of current thinking.

Artists and scientists both build upon the work of others. Scientists may repeat someone else’s experiment, or develop a new idea and experiment directly from theirs. In either case, they must explain their thought process and provide a clear reference to the previous scientist’s work when writing their paper. When artists are directly responding to a particular work of an old master, they might title their work, e.g. “…after Rembrandt”. Much more commonly, the influence of the old master on the new piece of work is more vague. Those “in the know” might recognise a similarity of e.g. brush-strokes or colours, but the old master in question need not be formally credited.

There is a horror of plagiarism in both art and science!

Here is a quotation from John Maeda (president of Rhode Island school of design) : “Artists and scientists tend to approach problems with a similar open-mindedness and inquisitiveness — they both do not fear the unknown, preferring leaps to incremental steps” (this is from Scientific American, July 11, 2013, but I have added the highlighting).

Scientists have a great understanding of what is subjective as opposed to objective. Do artists have a similar understanding? It is easy for artists to get caught up in myth and subjective opinion. The evaluation of the work of artists is also very subjective. However, artists have a great understanding of looking at something in the real world objectively. Those who have gone through rigorous life-drawing training know all about illusions caused by foreshortening, and can still understand the model’s structure without being misled by skin tan-lines or reflections.

Further thoughts

Following this introductory overview article, I plan to publish further thoughts on this subject. The next article will explain the scientific method more fully (e.g. what is a hypothesis?) and show how this compares to the artistic process.

Future articles are also planned, entitled “What can artists learn from scientists?”, “What can scientists learn from artists?”, and “Art and science: The sharing of knowledge”.

If you are longing to join in the discussion, then please do add your opinion in the “comments” box below (or alternatively write to me via the contact page if you’d prefer to express an opinion privately).

Error: Contact form not found.

| Tags: art and science, Leonardo

Art and memory: Developing skills

November 7, 2013

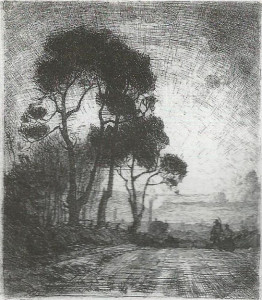

Above: Leslie Moffat Ward “Trees near Holdenhurst”, 1913, etching

Some techniques used by artists to develop the application of memory

Approach these “exercises” in a playful, experimental way and in any order that you prefer. They are really mind games rather than true drawing exercises. These methods are primarily designed to change the way that you see and remember. Approach with an open mind, and with plenty of cheap paper at the ready…

1) “Seeing pictures”

This is a technique that you can use anywhere. It is a great boredom-buster at the bus-stop.

Simply look at the scene in front of you, and visualise all or part of it in your mind as a picture composition. To start with, just be aware of this scene as a potential picture while you are still looking at it. Then try looking away from the scene…can you still remember the essentials of the image?

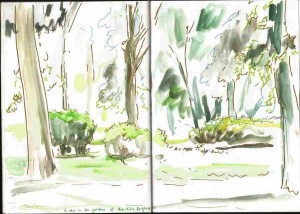

Above: The camera records a view of trees in all its complexity. Simplify the image by considering it as a group of dark-toned shapes against a light sky. You may also want to remember the horizontal strip of light across the distant edge of the lawn.

What is the point of the “seeing pictures” mind game?

This really is just a mind game. It is primarily useful in increasing our conscious awareness of what we are seeing. By trying to commit the scene to memory, we initially have to select what has greatest importance to us (e.g. bold shapes and tones as opposed to fiddly details). Such a selection process is key for many artists. In addition, attempting to remember visual images can, over time, improve memory skills.

“Seeing pictures” also helps us to make the mental switch from looking at the world around us, to portraying something of that world on a (usually rectangular) piece of paper.

Tips:

Most pictures are rectangular, so you may wish to think of the image in a rectangular (landscape or portrait-style) format. You could hold up a cardboard viewfinder to view the scene within a rectangular frame, or without a viewfinder you may be able to mentally “crop” the image, so that you are just considering a rectangular section of it.

Good scenes to start with are simple ones with strong tonal contrasts, e.g. trees silhouetted against the sky.

Don’t try to be a camera! Remembering detail is not necessary. Attempt to remember some or all of the following “essentials”:

Simple tones (very dark, very light and somewhere in-between)- e.g. dark trees against a light sky

Simple shapes – e,g. the shapes of trees massed together, and the shape of the sky around those trees.

Any movement– e.g. are the trees being blown one way or the other by wind?

and perhaps, broad areas of warm vs. cool colour

Though you are not trying to be a camera, you can effectively “zoom in” to the scene to visualise a rectangular image of just a small part of your view, if you wish. You could achieve this by holding the cardboard viewfinder further away from your eyes, if you are using one.

Above: Any part of the view could be considered as a potential picture. Here is a section of tree canopy selected from the previous image. How would you go about memorising this? Consider the shapes of canopy “clumps” (rounded, perhaps like bunches of grapes), and of the negative shapes of sky between the leaves and branches.

There are different ways to remember a scene. Experiment and see what works best for you:

1) You may intuitively remember a bold shape in the scene by simply focusing on the shape and memorising it.

2) A shape may remind you of something else. For example, a complicated space between tree branches might look, to you, like a pair of frantically-running legs. Remembering the image of running legs may later help you to recall the shape of the gap between branches.

3) Or you could take more of a logical approach. For the example of trees against the sky within an imagined rectangular “frame”, consider the most important proportions within the image. Would the trees reach the top of the image, or come perhaps just halfway up, or three-quarters of the way up the picture? How far do the trees reach across the image sideways? Is the mass of trees taller than it is wide, or vice-versa? Are the main trunks of the trees vertical? If not then how much do they tip and in which direction?

Developing this idea further:

a) Remembering moving images.

Once you get confident with this visualisation trick, then try it when the scene is moving past you, e.g. as seen from the window of the bus or perhaps, out in the countryside, from the back of a horse. Camera analogies are unavoidable here… Can you remember a “snapshot” image of a simple scene? How much is the human mind capable of in this regard?

A note about cameras:

I advise against taking a camera snapshot to back up your visual memory unless you really know what you are doing. Most photos capture super-human detail, but subtly distort the essentials of the image, i.e. the tonal gradation and the field of view. For capturing essentials, your eyes and brain are generally better than the camera.

On the other hand, we can learn from the great photographers who are truly aware of what they see. In the words of Henri Cartier-Bresson, “…one has to feel oneself involved in what he frames through the viewfinder. This attitude requires concentration, a discipline of mind, sensitivity, and a sense of geometry. It is by great economy that one arrives at simplicity of expression.”

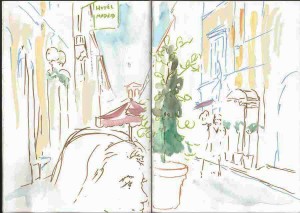

b) Thumbnail sketch of a remembered image

For a simple scene that is not moving, try visualising as a picture format as described above, and then turning around and making an immediate thumbnail sketch of the remembered image. For a thumbnail sketch, start by using pen or pencil to draw a rectangle in your sketchbook. The rectangle should be of similar proportions to your imagined picture. Draw in what you can remember of the scene starting with the boldest shapes. You could hatch or block in areas of tone with a soft pencil or broad pen.

Above: From my position in a car park, I could see interesting shapes in the tops of hedges and trees. I attempted to memorise a section, then turned around and made a thumbnail sketch. Here are three rather scribbly thumbnail sketches resulting from repeating the process with different parts of the view. This is just a learning process. I do not plan to develop the images further.

c) Sketching after visualising

Or, after visualising the image in your head, try making an immediate very quick drawing in your sketchbook while still looking at the scene. Include only the essential broad shapes, directional lines, tones or colours.

Above: I happened to have a few coloured pencils to hand when I drove past this group of sheep late on an autumn day. What struck me from the car was the appearance of the sheep as rounded masses, with yellowish sun slanting over their backs. In stopping the car and making a scribbly sketch, this was all that I attempted to convey on paper.

d) Sketching moving images

Have a go at drawing views from the window when you are on a moving train. Again, just focus on the very basics. There may be a bold shape of land beneath a block of sky, perhaps with a shape suggesting a line of trees or buildings.

Above: In a pocket-size sketchbook, here is one of many views from a moving train

2) Sketchbook experiments

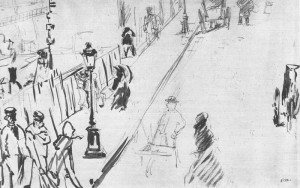

Above: Edouard Manet pen and ink sketch of La Rue Mosnet, c.1878

Like Toulouse-Lautrec or the young Matisse, take a sketchbook and draw people out and about. Avoid including much detail. Basic silhouetted shapes are a good start. Important things to note with figures include:

-

Is the torso upright or tipped?

-

In which direction is the figure looking?

-

Considering the person in their clothes as a single “mass”, what basic shape are you looking at?

-

Are the legs and feet out at an angle, or are they directly under the head?

-

The simple silhouetted shape of the head, neck and shoulders tells us plenty about character and identity, as described further here.

Above: A sketch of a man waiting to be served at a café. This was simply an attempt to capture his posture on the page.

Using a sketchbook in this way makes us look and then record what we see in the most direct way possible. It also allows us to experiment with that curious natural ability that humans have of being able to look at something, perhaps from a distance and in poor light, and “knowing” immediately what it is.

For example, you might see a child with their head turned away from you. Even from a distance, you would recognise this figure as a child. You may have a good idea as to whether it is a boy or girl, their age and even some idea of how they are feeling. But can you sketch the child’s figure in this position in any meaningful way? If not then why not? What is it that you are seeing, and how can that be transferred to the paper? Experiment with different drawing approaches to discover what is most useful, e.g. flat tone, hatched lines, simple outlines.

There is a current vogue for beautifully-finished artist’s “sketchbooks”, completed as publishable journals. My suggestion is to use a working sketchbook in a more experimental way, and not to mind if many of the drawings are scribbly, “sketchy!” or even incomprehensible.

3) Drawing a dream

Above: Charles Hazelwood Shannon “Shepherd in a Mist”, 1892, lithograph

For those who wish to link art in with emotion and memory, dreams have great potential.

The memory of a dream may be curiously incomplete and fleeting. We are sometimes left with a strong emotional memory on awaking, as if we have actually lived through a new experience.

Do you ever remember your dreams? If so, is this a visual memory? Like a fascinating piece of art, the initial visual memory of a dream may seem to be shadowy, incomplete, perhaps comprised merely of odd glimpses, while still representing a strong emotion.

Try this:

- You can only do this “exercise” on waking from a dream. Try keeping a notebook or sketchbook by the bed, as any visual memory of the dream will alter within minutes.

- As soon as you wake, note down anything that you remember from the dream. Use a combination of simple drawings and words.

- Be honest with yourself as to what you remember seeing in the dream. For example, the dream might have centred on a friend of yours, but perhaps you only remember seeing them as a shadowy shape. In your notebook, draw the shadowy shape rather than “making up” a drawing of the friend. Your notebook drawing may appear rather abstract. That is still interesting and valuable.

- If you don’t have the time, skill or media to convey the image fully as an immediate sketch in the notebook, then add words to further describe what you remember. For example: Which way was the friend looking? Were they moving?

- If the dream involved a sequence of events, then is it best conveyed as a series of drawings like a storyboard, or do you just remember odd glimpses here and there? Again, be honest with yourself as to what you remember.

Taking the idea further:

A collection of visual and written notes about dreams is fascinating in itself. In recording dreams, you can learn something of how emotion ties in with visual experience and visual memory. That is what art is all about.

It is not essential to develop any of the notebook images into finished pieces of art, but there is plenty of potential to do so if you wish. Whether you work towards producing an abstract or representational image, take care to include your genuine visual memories of the dream rather than constructing new images based on the dream’s story. The remembered images may well be shadowy, incomplete and ambiguous.

Above: An example of an image developed directly from a dream. Having dreamt about my old dog having a conversation with me (!), the resulting visual memory was of the front part of my old dog’s face. In my immediate sketchbook image, the animal’s mouth was closed and still as I remembered it from the dream. Without that initial sketch, I would have assumed that a talking dog would have a moving mouth. The dark areas with no form or detail were also remembered, and struck me as curious when I woke up. This charcoal drawing was later drawn using the sketchbook image and notes..

4) Drawing something that gives you an emotional reaction

What, in your life, gives you an emotional reaction when you look at it? Perhaps it is the face of someone dear to you? Perhaps your pet or favourite possession? If that feeling is important to you then play with “banking it” within your memory (i.e. deliberately remembering it).

When you look at this person or thing, then what exactly do you see that triggers the emotional reaction?

For example, if it was a person, then consider whether it was the shape of their face (as is so often involved in recognising someone from across a room) or perhaps the texture of their hair or skin, the shape of the top of their head (a common emotion-trigger when a parent looks at a tiny child) or something about their posture or gaze.

Now…can you “visualise” something essential that you have remembered of that person or object in your mind?

If so, then that is an excellent start.

Above: David Bomberg “Self portrait with a pipe”, 1932, oils. Under many lighting conditions, we see a series of characteristic light and dark shapes when we look at someone’s face. The shapes of the eye sockets , forehead and shoulders tell us plenty about the person’s identity and character.

You could then develop the eyes-brain-emotion-memory skill by exploring your surroundings further. There may be far more mundane objects that induce some kind of fleeting emotional reaction in you, whether positive or negative.

You might, for example, look at a section of peeling wallpaper and feel anger or frustration. Again, store the exact emotion in your “memory bank” (that does not mean that you need to be left feeling angry or frustrated for the rest of the day). What did you see of the object that brought on that emotional response? In the case of the peeling wallpaper, it might be the shape of the exposed wall, or the texture of the wallpaper edge, or perhaps something of the colour of the paper.

Taking this idea further:

Try drawing the person or object, taking care to include whatever factor triggered your emotional response. So, for example, you may feel happy when you spot your dear friend across the room, and perhaps you have decided that it is the exact shape of their face that triggers your emotion. Try drawing them, paying careful attention to that shape. A blocky tonal approach in soft pencil or charcoal may be good in this case.

Approach this drawing “exercise” in a very experimental way. You may find that your initial drawings are rather meaningless. Why do these early drawings not trigger the same emotional response as you experience when looking at the person “in the flesh”? Try different drawing approaches in various media and see what works best.

| Tags: essence of an object, exercises, Manet, memory, sketchbook, sketches

The essence of an object: the role of memory

October 19, 2013

How does memory tie in with the creation of art?

A quick internet search for “memory & art” directs me to websites in which events or people are commemorated in painting, sculpture and other media. Further searching leads me to information on those who use childhood memories to create highly imaginative and unusual work. Drawing from life can also be used to record fleeting memories, and it is interesting how many sketchbook addicts (myself included) claim to use drawing to back up an insufficient memory.

Above: Odille Redon “Pegasus Captive”, 1889, lithograph

What about the artist who sets about painting a still life or portrait? Is memory required for such a process?

To go through the mechanics of drawing a portrait does not require human memory. For example, take a look at the drawing robot. But artists are generally after something more than that. In order to create interesting work that can truly be described as art, perhaps the ability to process memory is essential …

…I’ll let you read on and come to your own conclusions.

“Drawing is remembering”

Once again, I am turning to Henri Matisse for ideas, mainly because he left a wealth of written and spoken information on the subject. Here I am referring to the excellent text of John Elderfield’s “The Drawings of Henri Matisse”.

Elderfield described how the young Matisse would go out with his fellow student Marquet to sketch in the streets of Paris. They attempted to draw silhouettes of people moving in the street. In Matisse’s words: “We were trying…to discipline our line. We were forcing ourselves to discover quickly what was characteristic in a gesture, an attitude.”

Above: Sketches of people and dogs drawn from life, this time by Toulouse-Lautrec. There is plenty of information here about posture and character. In particular, look at the shapes between and around the two dogs.

Attempting to draw moving figures is a real challenge, especially if the subject moves before the artist’s pen touches the paper. Elderfield writes, “sketching in the street…made it evident to Matisse that drawing was indeed not only a matter of observation but of memory: of recording, in fact, not what was seen “out there”…rather, what had been stamped in the mind. The act of drawing was that of remembering.”

Have you tried to draw people or animals who are continuously moving? When I have forced myself to draw, for example, equestrian vaulters on a cantering horse, I have struggled to come up with a meaningful image. To produce a drawing that is representative of the moving subject is a mental challenge that involves looking and thinking and a keen short-term memory for the essentials. A prior knowledge of the subject and a longer term memory is of course also helpful here.

Above: Some of my sketchbook attempts to capture poses of equestrian vaulters in action.

“My painting is finished when I rejoin the first emotion that sparked it”¹

So said Matisse. And he also gave great importance to remembering the initial spark of emotion that came at the beginning of the painting. Matisse wrote of looking at the subject (e.g. still life or figure) with an open mind and really observing the subject in a concentrated way. “..The subject is experienced, and drawing is the record of that experience, of the unconscious sensations which sprang from the model.”

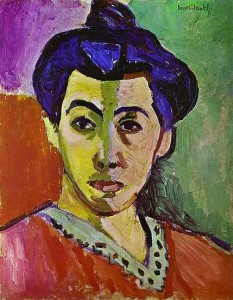

Above: Henri Matisse “The Green Stripe”, a portrait in oils of his wife, Amélie Noellie Matisse-Parayre, 1905

There is no point in trying to record the ever-changing present while it is taking place, as life goes on and the subject alters, as does the artist’s response to it. Even when drawing a “static” professional model or a pot plant, there are tiny changes over time. Consider changes in the lighting, the mood, and your (the artist’s) response to the subject.

Matisse believed that, instead, the artist must preserve the memory of the first concentrated observation. Elderfield interpreted Matisses’s outlook as follows: “To remember the first unconscious sensations which sprang from the model is to make a drawing”.

Rediscovering reality

In creating a drawing or painting, the artist may work up to a point at which their image starts to coincide with a recent or much more distant memory. They may think back to the initial “spark” of emotion of that day’s work. Alternatively, something about the image may start to resemble some other memory, recent or distant, within the artist’s mind.

Above: Pierre Bonnard “The Lunch of the Little Ones”, 1897

Proust wrote of “the grandeur of real art” involving the rediscovering of a reality that is “a certain relationship between sensations and memories which surround us at the same time”.

Is this fanciful?

No…. In going about our daily business (making breakfast, walking through the street, etc.) we are surrounded by all kinds of sensations and memories, both conscious and subconscious. As we walk through the street, we are not only aware of the pavement ahead , but also of surrounding buildings and people. Even if we are paying no direct attention to architecture, we are still certainly aware of being surrounded by, say, looming skyscrapers as opposed to neat residential houses. There may also be noise, perhaps traffic, birdsong or chattering people.

In addition, our head and eyes are continuously moving as we walk. Unlike a smoothly-gliding video tracking system, our eyes glance about all over the place, catching a glimpse of this here and of that there. We need some kind of very short-term memory system just to make sense of this. There might be a glimpse of the kerb, a flash of a car going by, a recognised face in the crowd, the brief sight of a cake in a shop window and also of our own feet as we step on the pavement. Much of this is mundane and quickly-forgotten. The occasional image (a girl in the street, a hat in a shop window) or combination of images may trigger a new emotion or distant memory. That is part of the human experience.

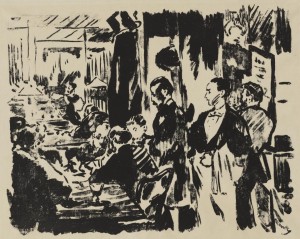

Above: Edouard Manet “At the café”, 1874, gillotage on beige wove paper. This complex image of a crowded room is simplified into rhythmic lines and strong shapes. Angles of heads are essential here, as are shapes of spaces between people. With a minimum of detail, Manet shares with us (across the centuries) the atmosphere of this noisy café.

Painting from memory

Henri Matisse said that he painted “from memory”. Numerous drawings made prior to a painting were created, not as first draughts, but to gain a deeper understanding of his subject. He wanted to know objects thoroughly before attempting to paint them: “Deep within himself…[the artist] must have a real memory of the object and of the reactions it produces in his mind”.

Matisse certainly did not transpose his drawings to a canvas in order to make a painting. He claimed not to be satisfied with a mere enlargement. Whether he used his drawings for close reference, or just put them to one side and truly painted “from memory”, I am not sure.

How can we use these ideas in practice?

The techniques and craft of painting can be learned, but what about the artistic, intuitive aspects? Is it possible, for example, to learn to improve our awareness and application of memory in drawing and painting?

Yes, certainly, with some careful thought and application, though it is a gradual process.

In my next article, I shall share practical suggestions on how to go about this using a series of mind games and simple drawing exercises.

1) Quoted by Pierre Schneider within “The Bonheur de vivre: A Theme and its Variations” lecture at MOMA, New York, 30 Mar 1976

| Tags: essence of an object, Matisse, memory, sketchbook

The essence of an object (2): The thing-ness of a thing

September 16, 2013

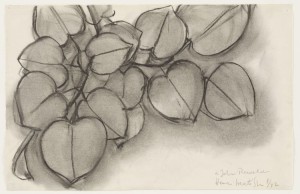

Above: Henri Matisse “Branch of a Judas Tree”, 1942, charcoal on paper, 25.2×39.4cm

Above: Henri Matisse “Branch of a Judas Tree”, 1942, charcoal on paper, 25.2×39.4cm

Writing in 1947 about some fig leaves that he was drawing, Matisse described how he was searching for the qualities that made them “almost unmistakably fig leaves”. He did not want to record exact copies of particular leaves, complete with their idiosyncratic folds and imperfections. Instead, Matisse worked to find the “common quality” that united things despite their visible differences. He wrote of searching for an “inherent truth” about the fig leaves.

As we can see from Matisse’s drawing of another plant, the Judas Tree, above, the general shapes and spacing of the leaves, and the shapes of the gaps between them, give the plant an immediate identity.

As humans, we find it easy to identify objects by their general shape (either the shape of an outline, or by the shapes of dark or light tones):

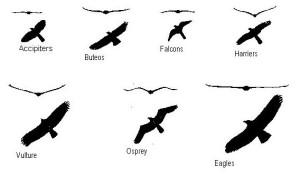

Above: Various types of birds of prey, quickly identifiable by their general shape

Thing-ness, identity and emotion

Though each differs from the next, all of the above bird silhouettes have a recognizable bird-identity. What is it that makes all of these shapes so recognisably bird-like; what gives them all a quality of “bird-ness”? It is the general shape, and the relative proportions of head, out-stretched wings and tail.

If we so wished, we could create a new imaginary bird silhouette that was still recognisably bird-like, without having been copied from any existing bird species.

When playing around with new bird-like shapes, when do our drawings lose the quality of bird-ness, i.e. when can they no longer be “read” or “understood” as birds? Feel free to experiment with this yourself.

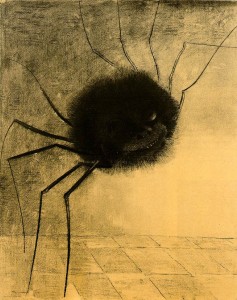

The quality of “thing-ness” can produce a strong emotional response. Imagine showing a drawing of a spider to someone who is terrified of spiders. You would expect them to be upset, whichever type of spider you had drawn. Now, what if the spider drawing was distorted. Would the arachnophobic person still be repulsed by your image? How much would you need to distort the image to make it acceptable to an arachnophobe? Would it be sufficient simply to make the legs of the spider extremely short, or to make its body very long, or to give it a different number of legs? To someone who has a great terror of spiders, you may need to distort the image considerably before it loses its quality of “spider-ness” for them.

Above: Odille Redon “The Smiling Spider”, 1891

The Platonic Ideal

This discussion of things and identity brings me to Plato’s ideas. He talked of the Ideal of a given form, which was the embodiment of all the particular examples of that form.

In order to see or imagine such an ideal form, one needs a reasoning mind. Here is an extract from “The Journal of Speculative Philosophy” Volume 4 , by William Torrey Harris, 1870:

“When Plato spoke of the goblet-ness and table-ness, Diogenes the cynic said, “I see indeed the table and the goblet, but not the table-ness nor the goblet-ness”.

“Right” answered Plato; “For though you have eyes which serve to see the table and the goblet, yet the wherewith to see the table-ness and goblet-ness, i.e. Reason, you have not”.”

Above: Raphael “School of Athens” , fresco, Diogenes is lying on the steps, and Plato is standing in front of the central open archway, wearing red and purple robes.

The perfect Platonic Ideal Form might be something that no human has ever come across. For example,

“No one has ever seen a perfect circle, nor a perfectly straight line, yet everyone knows what a circle and a straight line are”. (based on Plato’s “Cratylus”, paragraph 389)

Above: Paul Klee “Error on Green”, 1930

How might the Platonic Ideal be applied to drawing and painting?

Artists have long intended to create images representing the perfect example of an object, being or landscape. They might go out with sketching tools in order to record the many random quirks of nature, but the final picture tends to be a long-considered ideal image. The artist collates all his or her previous observations in order to make a final enduring image.

When I talk here about the “ideal” image, I do not necessarily mean one that is the most beautiful or pleasing. It may rather be the image that best sums up the appearance of a stormy sky, or the character of a complicated individual.

John Constable gave lectures on landscape painting at the Royal Institute in 1836, and this is what he had to say about condensing information into an ideal image:

“…the whole beauty and grandeur of Art consists…in being able to get above all singular forms, local customs, particularities of every kind…

[the painter] makes out an abstract idea of their forms more perfect than any one original”

Above: John Constable “Cloud study, horizon of trees”, oil on board, 1821. Though he was a great observer of landscape detail and weather change, Constable strove to create a perfect final image that summarised and surpassed all of this.

How do we recognise objects?

The human brain performs an amazing feat when it identifies an object. We take the complexity of this task for granted. Take, for example, our ability to recognise a pencil as a pencil, at first glance and without thinking about it. The pencil could be under any type of lighting conditions, and could be in any position. It could be any type of pencil. The possibilities are endless. In addition to this, our heads tend to be moving all the time as we go about our daily lives, so our eyes’ view of the pencil would be moving and fleeting, rather than a fixed frame like a photographic image.

In his fascinating paper, “Art and The Brain”, published in Daedalus in 1998, the neurobiologist Semir Zeki proposed that we have a kind of Platonic Ideal of each object in our mind “such that a single view of an object makes it possible for the brain to categorize that object”. He suggests that this Ideal image would be developed from the brain’s stored memory record of all the views of all the objects that it has seen. Considering the Platonic system, Zeki writes that “there can be no Ideals without the brain”. So the brain is of great importance here.

Which part of the brain is most involved in object recognition? According to Zeki, it is a region known as the inferior convolution of the temporal lobes that somehow processes stored memory records of all previously-seen objects.

The purpose of art and the “Ideal” or quintessential image

We look at real-life objects in many situations and remember numerous images of them. In addition, we can add to our brain’s stored memory record by looking at pictures. Art helps curious people to learn about the world, and pictures that portray a quintessential, or Ideal image have a special function here.

According to Zeki (Inner Vision 50-51), art, like the brain, seeks:

“to represent the constant, lasting, essential and

enduring features of objects, surfaces, faces, situations, and so on, and thus

allow us to acquire knowledge, not only about the particular object, or face,

or condition represented on the canvas but to generalise from that to many

other objects and thus acquire knowledge about a wide category of objects or faces”.

The art of simplification

Above: Henri Matisse “Young woman sleeping in a Rumanian blouse”, 1939, charcoal on paper, 37x47cm

Above: Henri Matisse “Young woman sleeping in a Rumanian blouse”, 1939, charcoal on paper, 37x47cm

Referring to the process of drawing a clothed figure, Matisse said:

“The fabric of the blouse has a unique character. I want to express, at one and the same time, what is typical and what is individual, a quintessence of all I see and feel before a subject.”

How should artists go about achieving this “quintessence”?

For many, simplification is key.

For example, many of Eugene Delacroix’s journal entries discuss the importance of suppressing detail. Here is an extract from 23 April 1854 in which he discusses the way in which an artist keeps the first pure expression throughout the execution of his work:

“can a mediocre artist, wholly occupied with questions of technique, ever achieve this result by means of a highly skilful handling of details which obscure the idea instead of bringing it to light.”

Matisse himself is known to have worked over many of his drawings repeatedly, not adding and over-working the image, but erasing and replacing marks until he was satisfied that he had placed each curve and line optimally.

Here Matisse describes his simplification process when drawing lace:

“You see here a whole series of drawings I did after a single detail: the lace collar around the young woman’s neck. The first ones are meticulously rendered, each network, almost each thread, then I simplified more and more; in this last one, where I so to speak know the lace off by heart, I use only a few rapid strokes to make it look like an ornament, an arabesque without losing its character of being lace and this particular lace. And at the same time it still is a Matisse, isn’t it?

I like Matisse’s emphasis on drawing studies until he “knows the lace off by heart”, i.e. has a deep understanding of it. In fact, once the stage of knowing the object off “by heart” is reached, the artist is capable of making a simple drawing from memory. In conveying the essence of an object, memory is of the utmost importance. But I shall come back to this point in a future article.

| Tags: blog, Delacroix, essence, essence of an object, Ideal, Matisse, Plato, Zeki

The essence of an object

August 26, 2013

Above: Henri Matisse “Blue Nude”, gouache and collage, 1952

Here is a phrase that I often come across: “Convey the essence of the object (or figure, landscape, etc.)”. These words are repeated in books, art classes and demonstrations. Is this just meaningless “art-speak”? I have been wondering… What on earth is an object’s essence, and how can an artist set about conveying it?

With my background in both science and art, I have been happy to seek more information. I’ve been looking at writings of neuroscientists such as Semir Zeki as well as those of artists including Delacroix, Matisse and Hockney. Looked at from multiple viewpoints, the subject is fascinating, and I’ll share my ideas with you here in this and some future blog posts.

A response to the French Impressionists