Drawing horse heads: The main planes of the head

May 31, 2012

Today I explain the basics of horse head structure for artists

Quite a lengthy post this time, but plenty of ideas and beautiful images to enjoy….

First, a quick look at two-dimensional horse head images

A very simple horse head can be drawn using just a few lines to create a recognisable and beautiful image. For example, the following drawings have great character, spirit and symbolic meaning. On the left we have charcoal images made about 30,000 years ago on the walls of the Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc cave in southern France. On the right is a logo created for Madinat Jumeirah, a luxury hotel in Dubai. This head is created from Arabic calligaphic letters that translate as “The Palace”:

The beauty of these fantastic images, above, lies in their incredible use of line and space. The shape of the horse head can make a wonderful two-dimensional design on the page or wall.

Drawing in a more three-dimensional way gives you more scope as an artist

When faced with drawing a real horse from life, it can be tempting to aim straight away for the “iconic” profile illustrated above, perhaps working largely from memory. However, this approach risks missing much of the beauty of the living creature.

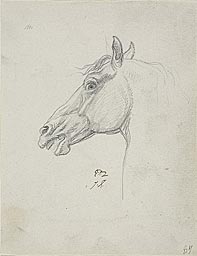

On the other hand, here are studies made with real understanding of the horse’s structure. That on the left by Perina del Vaga (Rome, 1501-1547). The study on the right was by Leonardo da Vinci.

Understanding the actual three-dimensional shape of the horse’s head allows us to produce work that relates more closely to our experience of the animal in real life. This empowers us to draw the horse from any angle and to understand the fall of light and shade on it. We can then return to more two-dimensional work, if we wish, with a fuller understanding of our subject.

Planar analysis and heads

A “plane” of an art subject is considered to be a flat and level part of its surface. In studying the human head, some artists aim to simplify its shape into a number of planes. This process is called planar analysis. Where possible, these planes are made flat (though some do curve slightly) and adjacent planes meet at a sharp edge. It is even possible to buy a special model to study and work from for human heads, the one below being available from from the website: Planes of the Head

Why bother with planar analysis?

- This way of working ensures that we understand the structure of our subject.

- It helps us to get the light and shadow correct. Planes facing the light source will be very light in tone. Those facing away from the light source will be in deep shadow. Planes that are in line with one another should have the same amount of light falling on them (assuming that there is no cast shadow, e.g. from a tree or from the mane of the horse).

- It helps a lot with foreshortening, especially once we start working without a live model.

- If the planar structure is emphasised, it can give a handsome, well-chiselled appearance to the image of the horse head.

Horse head structure: Notable points

I’ll go through the main planes and landmarks of the horse head in this today. There are Old Master drawings, images of statues and live horses to illustrate these points.

The diamond shape at the front of the head

At the front of the horse’s head is a fairly flat large diamond-shaped area. This is made up of some skull bones that are fused together, these being the nasal bones (running down the length of the nose) and the frontal bones (at the front of the forehead). When simplifying for artistic purposes, we can consider this diamond to be one flat plane.

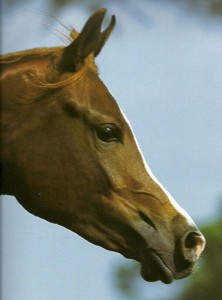

The sculpture above is a horse head by Nic Fiddian Green in London. I have included it to show how light will illuminate the front of the horse’s head in a diamond shape. The sculpture is somewhat stylised, but see how the relationship between the eye and the diamond-shaped plane is the same in the sculpture and in the photo of the live horse, above.

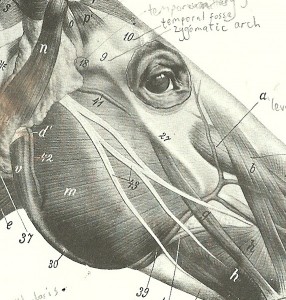

Here are diagr ams from “An Atlas of Animal Anatomy for Artists” by Ellenberger

ams from “An Atlas of Animal Anatomy for Artists” by Ellenberger , Dittrich and Baum, showing that diamond-shaped area at the front of the horse’s head. Run your hand over the front of a real horse’s head and you’ll be able to feel the bone just under the skin in this area.

, Dittrich and Baum, showing that diamond-shaped area at the front of the horse’s head. Run your hand over the front of a real horse’s head and you’ll be able to feel the bone just under the skin in this area.

In fact, there is a slight crevice along the centre of the horse’s head in the middle of the “diamond” (see diagrams above). It always helps to have a midline marker when drawing a complex subject, so feel free to make good use of this one.

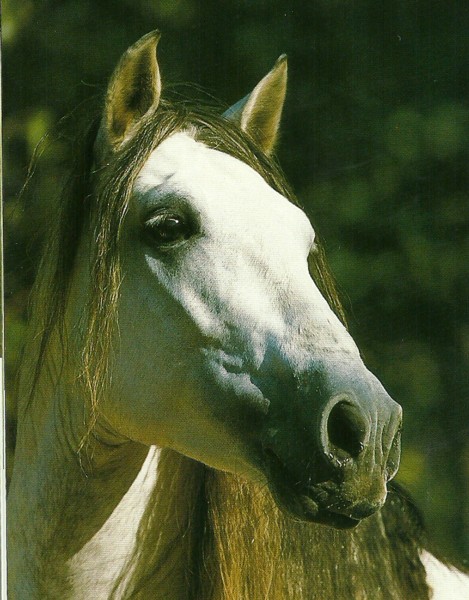

In the photo, below, of a fine horse from the Kent-based stud “Dancing Green Lusitanos”, the bone structure is very clear. The left side of the horse’s face is in shadow. See the shape of this shadow, and the clear change of plane between this shaded area and the front of the face. The slight groove down the centre of this horse’s nose is also visible in this picture

Masseter muscle of the cheek

Now consider the semicircular cheek muscle at each side of the head. This is the Masseter muscle, and in real life its surface is almost a flat plane without needing any simplification. On the left, below, is another detail from Ellenberger et al’s “An Atlas of Animal Anatomy for Artists”, the Masseter muscle being labelled with an “m”. On the right is a drawing by Jacques Louis David with the Masseter muscle clearly shown:

Go up to a friendly horse and stroke your hand over the semi-circular Masseter muscle. Feel how flat this muscle is. At the front edge of this muscle, you’ll encounter a sharp change of plane and a “step” as the horse’s head narrows at this point.

The facial crest

Try running your hand up over the flat Masseter muscle towards the eye. Here, you’ll encounter a bony ridge and a definite change of plane. This bony ridge is the zygomatic arch, which is also called the facial crest (labelled 27 in the above diagram). Be aware of this ridge as it is a very prominent feature on every horse head. See how the facial crest is illuminated by sunlight in this photo, and how it casts its own shadow:

This photo of a horse sculpture on an old stable building in New York (below left) clearly shows the structure of the Masseter, facial crest and surrounding planes, as does the photo of a horse, below right):

To further illustrate the marked change of plane at the edge of the masseter muscle, here is a photo of Nic Fiddian-Green working on his horse head sculpture as it is installed at Ascot racecourse. See how there is space for him to fit his body in along the giant horse’s nose while his right arm is in line with the facial crest:

The round Masseter muscle makes a fantastic shape within a composition. Make good use of it if you can.

Here is Delacroix‘s dynamic drawing based on a horse from the Parthenon sculptures. See how hatched lines follow the changing planes to give a clear sense of form. The rounded shape of the Masseter muscle and of the eye contrast here with the more angular, choppy shapes around the nose and ears, contributing to the powerful design:

Position of the eye

Let’s now consider how the eye fits into the head. First, notice that the eye and its lids are embedded within a deep hollow in the skull, the bony orbit. So, though the itself is large and round, only the surface of it protrudes:

The eye within its bony rim is set at an angle. The lowest corner of each eye (the corner nearest to the nose) is closest to the midline. The clearest illustration for that is, again, the New York horse sculpture on the old stable building:

Also see the angle of the eye of this statue by Leonardo da Vinci:

And in the real horse:

What is the widest point of the horse’s head?

The very widest point of the head is at the orbital arch, which is the rim of bone just above and behind the corner of the eye:

The funnel-shape above each nostril

All I shall say about the nose today is that there are muscles in the shape of a funnel or pyramid attached to each nostril. These can pull the rim of the nostril outward to enlarge or dilate the nostril:

The temporal fossa

Note the concave valley, the “temporal fossa” which is just above each eye and a little towards the midline (marked “10” on the diagram below). In some horses this fossa is more of a flat plane. In very thin horses and in those of certain breeds such as Arabs, the temporal fossa is a deep hollow.

The ridge of the Zygomatic arch

There is a bony ridge extending from the upper corner of the eye back towards the base of the ear. This is the “zygomatic arch” (not to be confused with the zygomatic crest) and is labelled “9” on the diagram above.

Here is an Arab horse with a very prominent zygomatic arch extending back from the eye:

The region between the corner of the mouth and the Masseter muscle

The muscles here form ridges and valleys that move as the horse chews food and sometimes when he is excited.

Do look again at the Arab horse profile view, above, to see these muscles clearly defined. In some situations, there is a clear change of plane extending back from the mouth producing a dramatic shadow. See how the light affects these planes in the Arab head above, and also in this close-up view of Robert Glen’s Las Colinas Mustangs (Texas) :

Now what?

The best way to understand the structure of the horse’s head is to get to know a horse in real life, and to feel for yourself where all of those “landmarks” and changes of plane are positioned.

Modelling a horse head in clay or simply in Plasticine will also do wonders to improve your understanding.

This very lengthy post has really just overviewed the structure of the head. I shall happily post in future in more detail, e.g. about the eye area.

News and workshops

I shall be travelling in the coming week, so am taking a short holiday from adding to this blog.

There are still places available on the Horse Life Drawing day on June 17th near Ware, Herts. If you are interested, please do get in touch. You can phone or email if you already know me, otherwise click here: Contact

This workshop is open to all, from sixth form school students up to very experienced artists.

Links

Dancing Green Lusitanos (Kent-based stud with beautiful horses)

“An atlas of Animal Anatomy for Artists” by Ellenberger et.al (My favourite artists’ anatomy book) see link below: