Dance and art part 2: Some practical approaches to drawing or painting the dancing figure

December 1, 2020

Drawing or painting a dancer presents us with a special problem. How can we use a still image to represent a moving figure?

There are many possible ways to go about this intriguing challenge. Part 1 of this two-part mini series gave tips on suggesting movement and expression when painting or drawing dancers. Part 2 now goes on to focus on some practical approaches to drawing or painting the dancing figure.

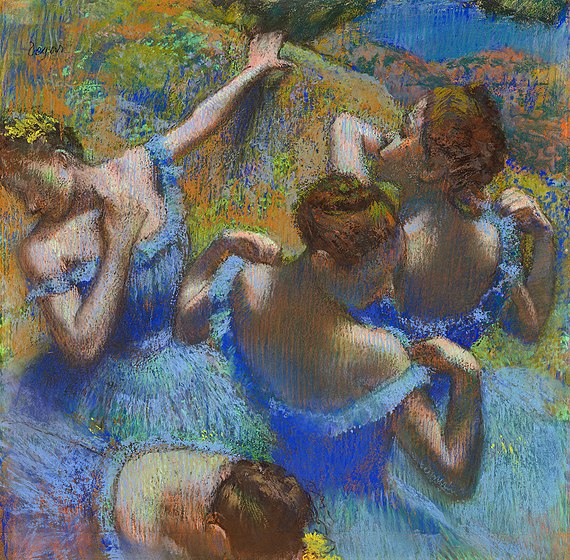

Above: Edgar Degas “Blue Dancers”, 1897, pastel

Approaches to drawing dancers include:

Sketching dancers from life in the theatre or rehearsal room

Drawing from the posed dancer hired to model in costume in the studio

Working in the studio from photos

Working in the studio from video footage

Drawing or painting without a current reference, using a combination of memory and imagined images.

It can be useful to combine at least two of the above methods.

Drawing the moving dancer from life

Sketching someone as they dance is of course extremely challenging: It involves trying to record the present while it is taking place before it can slip into the past. It feels impossible! Why should the artist attempt such a thing?

Drawing from life gives us the opportunity to experience the dance on an emotional level rather than simply recording mechanically. An artist who observes the dancer in real time is in a position to convey the emotional impact of that experience. Resulting images won’t be photorealistic. But perhaps this is not what we are striving for:

“It is the artist who is truthful, while the photograph is mendacious; for, in reality, time never stops cold”

Auguste Rodin

James A.M. Whistler “Louie Fuller dancing”, 1892, pen and black ink

Some practical tips for drawing a moving dancer from life:

Take a little time to observe the dancer(s), to absorb the atmosphere and to listen to the music before starting to draw.

It can help to start by sketching in a few lines to suggest the background. The dancer’s surroundings do not move and can therefore become a helpful reference for you. If outdoors, where is the horizon line? If indoors, lay out a few marks to suggest the floor (e.g. edge of a rug or floorboards), and perhaps mark on the page where the floor meets the edge or corner of the room.

The dancer can be drawn using a rapid almost continuous line, barely lifting the pencil, paintbrush or pastel from the page.

Short sticks of pastel or charcoal could be turned on their side to block in broad directional marks of colour and tone

Do not be too hard on yourself: See if you can capture your immediate visual response to the dancer rather than a “likeness” or totally “realistic” drawing. Some drawings made from the moving figure may look barely human, but they nevertheless capture something of the essence of the dance.

Drawing the posed dancer

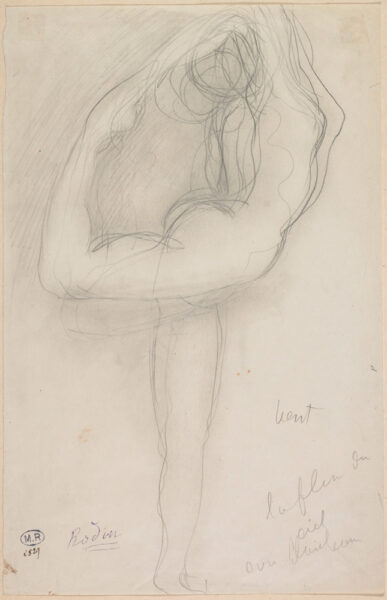

Once his studio was well-established, Auguste Rodin (1840-1917) tended to have several models available through each working day. While one might be stretched out on a pedestal, others might be just wandering around. If one made an interesting movement, he would shout out “Halt, don’t move”, and start working. Rodin’s models included dancers and acrobats such as Aldo Moreno.

Auguste Rodin “Standing Nude Holding her Right Leg”, c.1903, pencil with stump on paper

Not every artist has the chance to draw from a posed dancer model. If you’re lucky enough to get this opportunity, then discuss in advance how they could best help you. Be reasonable and understanding. Don’t pressurise a dancer to hold a long uncomfortable static pose, e.g. with arms raised or balanced on one leg. This can lead to injury – the last thing that a dancer needs. Give your dancer model plenty of opportunities to pause during the session in order to drink water, to move about or to stretch. One tried and tested approach is as follows:

Ask your dancer to come in costume. They could bring along a prepared section of dance and a recording of its backing music. Offer the chance for the dancer to “warm up” on arrival before you start.

Have the dancer demonstrate a 1-3 minute section of their dance along with its backing music. Observe, or make a fleeting sketch if you wish.

Continue with three 5-7 minute poses in fairly relaxed positions. Standing poses can work well, or the dancer could find a relaxed position on the floor, for example pretending to adjust a shoe.

Then ask your dancer to hold a series of very short poses lasting from between 30 seconds to 3 minutes. Put them in control – As they go into the pose, they’re to tell you how long they’ll be holding it for. This is tiring: Offer plenty of breaks.

You could also ask the dancer to pick out one very short sequence from their dance (nothing too physically extreme) and to perform this repeatedly over a period of around 1-4 minutes. From this, you could draw either a very fleeting sketch, or a semi-abstract looping form that just suggests the nature of the movement.

Complete the session as suits you both. You could request a longer (e.g. 30-45 minute) static pose in costume, with the dancer reclining comfortably against cushions or resting in a chair. Or your dancer may wish to perform their prepared piece again for you, along with backing music. Make fleeting sketches from this, and/or take photos or video footage from various angles for your future reference.

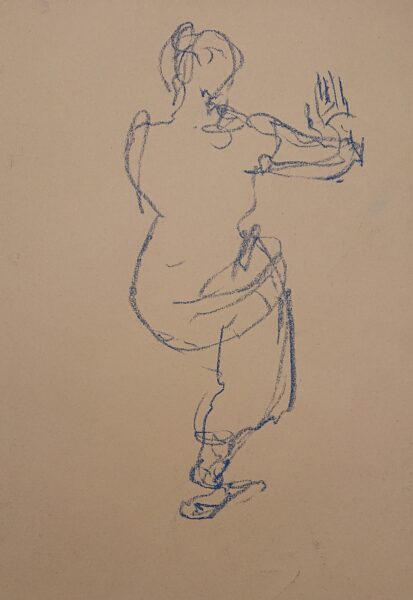

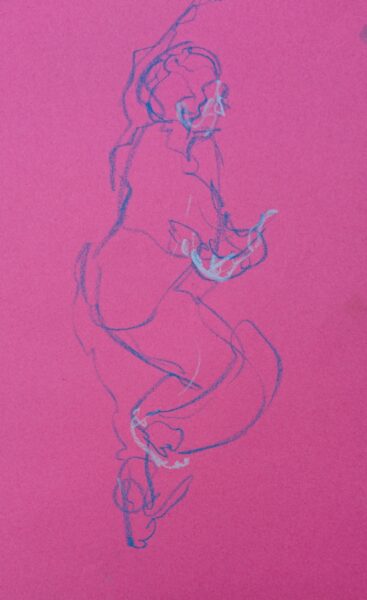

Above: M.Dorn, Three fleeting sketches of the Indian Dancer Fabrizia Verrecchia, pastel on paper

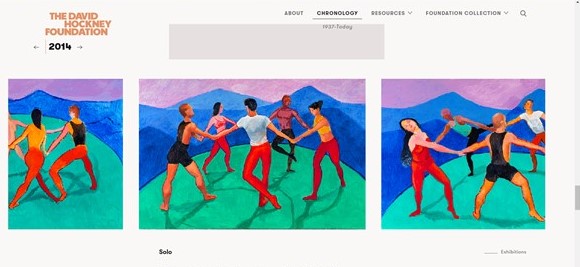

In 2014, David Hockney invited dancers to pose in his studio for a series of paintings, some taking their inspiration from Henri Matisse. This followed on from a period of using multiple viewpoint photography to overcome the “problem” of perspective. He wrote,

“The very first picture of the dancers was of them stood in a circle; it was ok, but they weren’t moving, they weren’t dancing. I got them to go around in a circle, then I would say stop, and draw one and I slowly built it up.”

David Hockney

Posing a group of models enabled Hockney to make anatomical sense of the figures, both as individuals, and as a group holding hands. Unlike a rapid sketch, this thoughtful and controlled approach has helped Hockney to create pleasing finished compositions. Each works on an abstract level, from the shapes between limbs, to the dynamic tension between forms, and the distribution of colours within each painting.

Drawing the dancer from photos

The camera can be an outstanding reference tool for the working artist. It captures vast amounts of information in an instant: For example limb angles, anatomy, patterns of light and shade, and the fall of folds of clothing. However, bear in mind these words of wisdom regarding the photographic representation of movement:

“Movement seized while it is going on is meaningful to us only if we do not isolate the present sensation either from that which precedes it or that which follows it”

Henri Matisse

This does not mean that working from photos must be completely avoided. Rather, photos can be used as an additional back-up reference tool if needed. They must be understood in context. What was happening just before and just after the photo was taken? How was the dancer moving?

To answer the above questions, it can be more useful to work from video footage (which you can then freeze-frame at a moment of your choice or replay on a loop).

Even when working from photos, try to get a sense of the “atmosphere” of the dance. Did the dancer(s) give an impression of easy elegance or exuberance, or tension? Was there a jostling crowd, a rapt audience, or an echoey empty room? It is best to be there at the live performance in order to absorb the experience before returning to the studio with your reference photos or video footage.

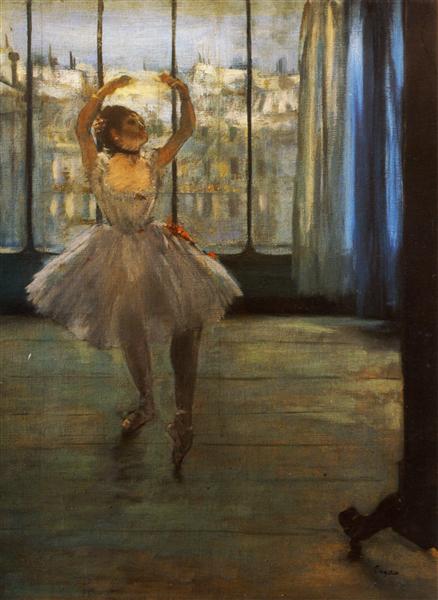

Above: Edgar Degas “Danseuse posant chez un photographe”, 1878, oil on canvas

Drawing the dancer from memory

Creating a picture of a dancer requires some memory drawing. This is the case even when working from the live model. Dancers move faster than any artist can draw or paint. Sketching the moving dancer therefore becomes an act of recording, not what the artist is currently observing, but what the artist remembers from some moments ago.

Perhaps you are working back in the studio after viewing a dance performance. In that case, memory plays a central role. Even with good photographic references to hand, the artist needs to think back to how the dancer was moving, the sense of tension in the dancer’s limbs, and so on.

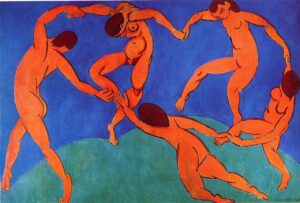

And of course the artist needs to remember their own emotion on viewing the dancer in the first place. In 1976, Pierre Schneider gave a lecture at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in which he quoted Matisse as saying,

“My painting is finished when I rejoin the first emotion that sparked it.”

Henri Matisse

In order to work in this way, take note of your first emotional response and then remember it throughout the creation of your piece of artwork.

Above: Henri Matisse “Danse”, 1910, oil on canvas, 260x391cm

The artist does not only refer to a posed model or to photos. Whether fully aware of it or not, she also has some internal “reference” – an internalised feeling or response to having watched the dancer.

This internal reference may just be a vague emotional response such as a sense of lilting grace. Or it may be a visualised idea of a highly developed composition ready to be produced on canvas. Or perhaps it is somewhere between these two extremes, akin to a remembered fragment of a dream.

Take note of that dreamlike “internal reference”. This can be the spark that takes an image beyond mere technical drawing and turns it into a work of art.

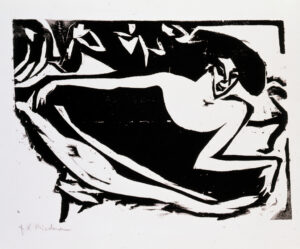

Above: Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Dancer with Raised Skirt, 1909 woodcut

References

Corbett, R. (2016). You must change your life: The story of Rainer Maria Rilke and Auguste Rodin. WW Norton & Company.

Elderfield, J. (1984) The Drawings of Henri Matisse. Thames and Hudson.