Shapes and emotion

May 6, 2014

Above: Leonardo da Vinci “Lady with an Ermine”

Shapes are essential to the character of each artistic image. Have you ever glimpsed a painting from a great distance, and understood something of the emotion conveyed by the artist even before discerning the full content of the picture? Along with tone and colour contrast, clear shapes within the image can help to convey this “emotional punch”.

Our innate emotional “understanding” of 2D shapes is perhaps even more profound than symbolic meanings assigned to them in different cultures. I originally read about this idea in “The art of responsive drawing”, an excellent guide to drawing and composition by Nathan Goldstein, and do recommend getting hold of this book if you’d like further ideas on the subject.

When looking at an image (either a full picture, or just a shape on the page) we react to:

- symmetry versus asymmetry

- corners and points of shapes

- curved versus angular shapes

Let’s look further at how artists have used various types of shape for emotional effect.

1) Flowing, lyrical, sensuous shapes

These shapes tend to be:

- Asymmetric

- Curve-edged

- Rather long

- “Organic” rather than geometric shapes

Above: Botticelli “Venus and Mars”, 1487-8, 70.6 x 176.8cm

The bodies and drapery of the two main figures in Botticelli’s “Venus and Mars “provide good examples of long, flowing shapes. Even the male figure of Mars, god of war, is made to look lyrical and sensuous here. Note how rotation through his torso and neck allows the creation of asymmetry and curves.

Meanwhile, clever draping of fabric creates similar shapes associated with the figure of Venus, goddess of love. Look not only at the whole reclining form of Venus, but also at the sections of fabric about her waist and limbs. The atmosphere in the foreground here is of flowing sensuality, though the long, lyrical shapes do not extend to the four cheeky, mischievous little satyrs in this picture.

2) Solid, dependable shapes

These shapes tend to be:

- Symmetrical

- Contain at least one straight edge

- Geometric

- “Blocky”

…but look at the examples in the box, above, and note that rules are sometimes broken! These shapes may also suggest strength and reliability.

Above: Edgar Degas “Hélène Rouart in her father’s study”, 1886-95, 161x120cm, oil on canvas

Hélène Rouart looks somewhat out of place in her father’s study in the image above. The strength of character of the study’s owner, wealthy collector Henri Rouart, is suggested by the shapes of his belongings. Look at the square-edged mirror, the painting on the wall, piles of papers and perhaps even the Egyptian mummy case. Set at an angle against the blocky structure of her father’s chair, the more lyrical forms of Hélène’s hands and figure contrast with the rest of the room. The young lady projects a sense of unease and seems constrained by the presence of her father even though he was abroad when this was painted.

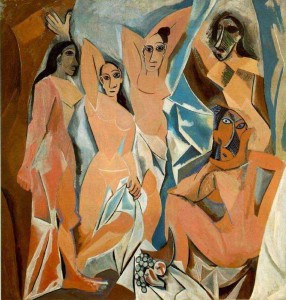

3)Violent, harsh shapes full of nervous energy

These shapes tend to be:

Angular Irregular Jagged Contain straight edgesAbove: Pablo Picasso “Les Demoiselles D’Avignon”,1907

In Picasso’s rather shocking image, above, the women appear confrontational and perhaps even menacing. Cubist rendering of the forms here creates jagged, irregular shapes that contribute to the potentially-violent atmosphere.

Jagged-edged, irregular shapes are frequently-seen in real life and in photographic snapshots: Think of gaps between tree branches, shadows and building edges seen at an angle. In creating an artwork, decide whether you wish to include, emphasise or suppress such shapes.

4) Gentle, rocking shapes

These shapes tend to be:

- Asymmetric

- Curve-edged, especially with a convex lower edge

- More often rounded than long

Above: Edgar Degas, “Portrait of Giovannina Bellelli”

Gently rounded shapes are easily formed by the play of light and shadow on young faces (see Degas’ portrait of a child, above) and, whatever the subject, they can suggest tenderness and empathy.

Further types of shape

Of course, not all shapes quite fit into these simple categories. Take a look, for example, at Leonardo da Vinci’s “Lady with an Ermine” (reproduced at the top of this page), an image with an atmosphere of lyrical grace and poise and full of strongly-emphasised shapes.

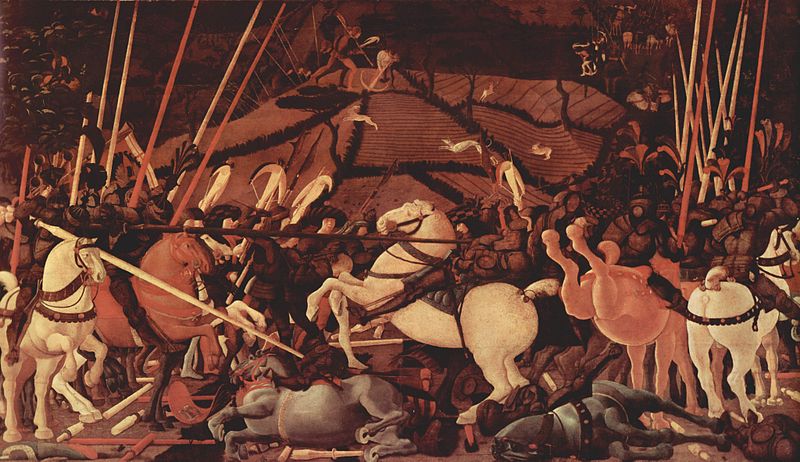

Or consider the carefully-placed structures in Uccello’s beautiful but horrifying image of war, below. This painting is full of curved-edged horses but, where lances cross the picture at an angle, numerous unsettling, angular shapes are created.

Above: Paulo Uccello “The Battle of San Romano”