Shapes in art

April 30, 2014

Mary Cassatt “The Long Gloves”, 1889

Whether we choose to produce figurative or abstract art, our drawings/paintings inevitably end up as a series of two-dimensional shapes on the page. Control shapes carefully, and this becomes exciting. Different shapes have the capacity to suggest specific emotions to the viewer, and even to hint at certain types of movement. Furthermore, a visual balance or echoing of shapes on the page can be intriguing.

Where are these shapes?

Above: Henri Matisse “The Sheaf” ,1953, paper cut-out

Abstract art, in some cases, is all about shape. Geometric or irregular “organic” shapes or forms may create the basis of the image (for example, see Matisse’s cut-out above)

But how can we achieve shapes in figurative art?

Seeing a whole object as one flat tone or silhouette is a quick way to achieve a clear shape: For a start, try viewing an object against a contrasting light or dark background. Backlit against a sunset, distant trees and buildings appear as simple shapes.

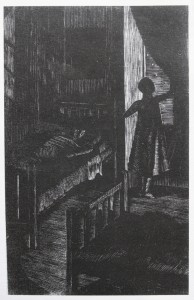

Indoors, try looking at backlit objects on your windowsill or look at people against the light for a similar effect:

Above: Helen Binyon (1904-1979) “The starry night”, wood engraving. The girl forms a silhouette against the starlit window. Meanwhile, objects within the dimly-lit room are reduced to semi-abstract shapes.

A patch of contrasting colour may also form a prominent shape within your image. This may be, for example, a patch of yellow light across a landscape. Or it could be a brightly-coloured object such as a red cup on a table.

Above: Claude Monet “Pathway in Monet’s garden at Giverny”, 1900, oils. Patches of bright sunlight form peachy-coloured shapes across the path between the dark, mauve-tinged shadows. Notice how the shapes of contrasting colour and tone repeat along the path and draw the viewer’s eye into the picture.

If you use a linear drawing technique, then you may find that your lines appear to enclose shapes . For example, see the strongly-outlined arms of Mary Cassatt’s “The Long Gloves” reproduced at the top of this article. Notice how these arms each form a boomerang-like shape, and how these shapes appear to echo one another.

By using shapes of shadow or high tone within your image, we can add interest to the composition while retaining the illusion of three-dimensional reality:

Above: Edgar Degas “Portrait of Giovana Bellelli”, 1858-9, pencil. Look at the patch of light tone on the girl’s right cheek, shaped like an inverted comma. Shapes of light and dark tone throughout this image are round-edged and asymmetric, increasing the lyrical, tender effect of this portrait.

Above: Edgar Degas “Portrait of Giovana Bellelli”, 1858-9, pencil. Look at the patch of light tone on the girl’s right cheek, shaped like an inverted comma. Shapes of light and dark tone throughout this image are round-edged and asymmetric, increasing the lyrical, tender effect of this portrait.

Intriguing “negative” shapes can also be seen between objects:

Above: Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, “Messaline”, oil on canvas, 1900-1901, 92.5x68cm. The red background forms prominent shapes between the figures and is very much part of the picture.

In my next article, I’ll suggest ways in which different types of shape can be used to suggest emotion in your pictures…