What can artists learn from scientists?

March 5, 2014

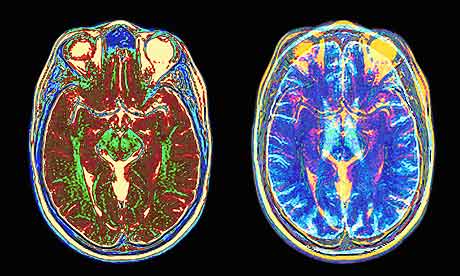

Images of the human head as recorded by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI scan)

Is it a good idea to use scientific ideas in your artwork?

Yes, perhaps, but watch out:

- I’d recommend fully immersing yourself in a subject before commenting on it artistically. Reference to a misunderstood scientific concept risks embarrassment, so do read around the subject and, if possible, get to know some experts in the field.

- Much that is published in the media as scientific “fact” is only applicable in certain contexts, or in some cases may even be flawed. Aim to speak to a variety of people in the know before coming up with your own opinion.

How about borrowing scientific imaging tools?

In opening up fresh opportunities for observation, scientific imaging can be inspirational to the artist. Microscopy, radiography (X-ray images), cineradiography (moving X-ray images), thermal imaging and slow-motion video analysis give us new insights into our world.

Some medical and scientific images are curiously ambiguous, being both beautiful in an abstract sense, and carrying specific meaning to those trained to understand them. For example, groups of cells seen through a microscope form striking patterns accentuated by first staining the sample on the microscope slide. Cross-sectional images of the body achieved by MRI or CT scanning often contain compelling shapes and can be curiously symmetrical.

As artists, we often look for visual patterns and trends while also seeking meaning. Be inspired by a current art-science exhibition on this very subject: “Beautiful Science: Picturing Data, Inspiring Insight” , is on display at the British Library until 26 May 2014.

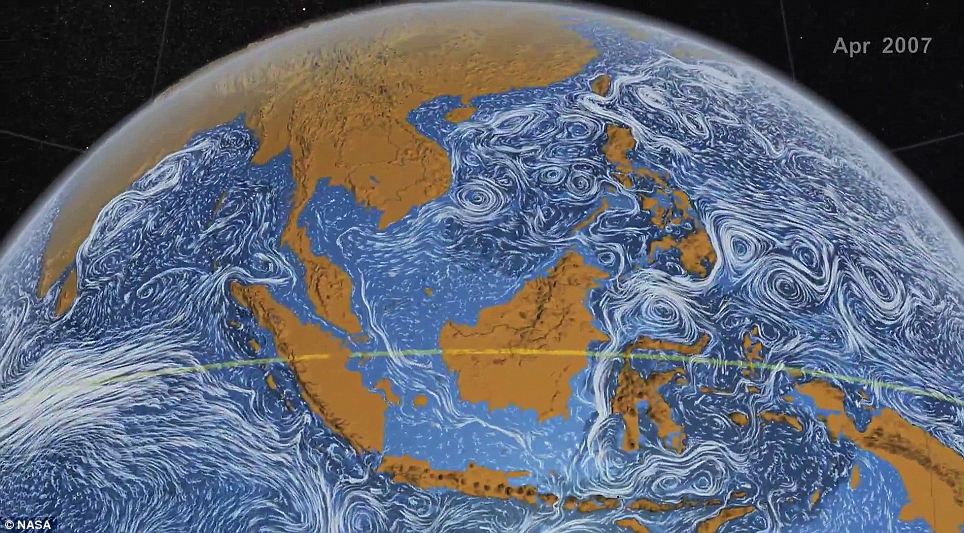

Above: Visualisation of ocean surface currents by NASA

“Scientific thinking” for artists: Some practical tips

Here follows a long list of suggestions. Different methods work for different artists, so just pick out anything that strikes you as useful.

Getting to grips with a practical problem

Freedom of expression and spontaneity are valued highly by many artists. Nevertheless, there are times in most artists’ lives when a lack of control of the medium hinders creativity. Established protocols for paint-mixing, etc., are no longer taught in many art schools, perhaps in order to leave students more potential for creative expression. How can an artist develop his or her own technical skill?

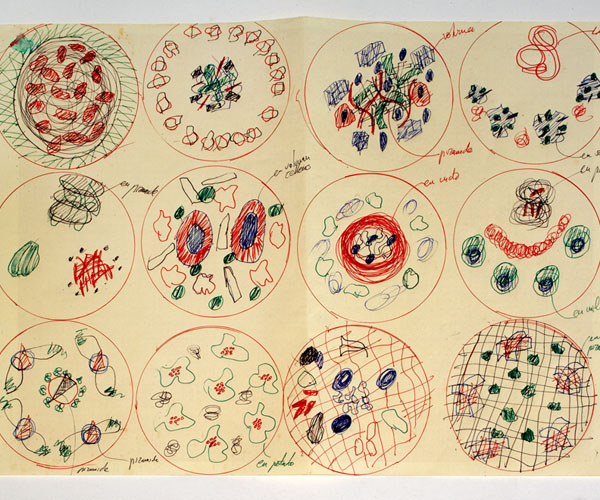

Trying things out (“trial and error”) can be very useful to the developing artist. If this seems like a frustrating business then go about it in systematic way and take the opportunity to record results. For example, keep a notepad by your easel and make a note of paint mix colours that work for you. Record what doesn’t work too. Learn from the example of the great creative chef Ferran Adrià, who is said to have rigorously recorded culinary creations that were successful but, just as importantly, recorded all unsuccessful food combinations.

Above: Ferran Adrià plating diagram, ink on paper. This great creative chef draws potential culinary ideas but also has a great system of recording results of food experiments as written notes. He said, “I always have a pencil with me, to the point where it forms a part of me. I write a lot during the day”

If you really want to get to grips with a practical problem then test it rigorously. First decide what you are testing. So, for example, you might be testing the suitability of different types of paper for use with inks. In this example, a few specific types of ink mark would be made on each type of paper. Of course, brand of ink, style of brush-stroke or pen-mark and quantity of water added to the ink would all affect the finished result, so these must not vary. Label each variety of paper, and either store the results in a plastic wallet file for future reference, or make a clear written note of the outcome.

Scientists are trained to focus on just one problem at a time, but this skill is also useful to artists. Do you ever find yourself completely overwhelmed and unsure of where to start, perhaps when drawing or painting an unfamiliar subject? In some cases, this sense of helplessness (“I can’t draw that“) is simply due to attempting to solve too many problems at once. Each new artistic subject presents a whole set of challenges or conundrums. For example, drawing horses from life can feel overwhelming to those who have never tried it before. Equestrian drawing involves all kinds of challenges including unfamiliar proportions, foreshortening, tones, colours, movement and textures. A positive approach is to make a series of drawings, each focused on a single area of concern, e.g. one drawing to investigate tones, another looking closely at 3D structure, etc.

Some finished pictures do focus on just one aspect of their subject and this can, at times, make the work more interesting and compelling. If, on the other hand, you wish to perfect several aspects of your subject in a finished picture, then you will need to solve multiple problems. For example, the colour of fur in sun and shadow is one “problem” while the way in which to make the animal look as if it is leaping is another. Before tackling your finished picture, investigate each problem individually by making preliminary studies, colour trials and perhaps also by observing the work of other artists.

Above: Rosa Bonheur “The Horse Fair” 1853-1855, oil on canvas. The creation of this complex image required great problem-solving skills: animal behaviours and movement, the effect of light and shade on each coat colour and the shapes within and between moving horses all needed to be understood. Rather than being overwhelmed by the task, Bonheur solved each problem in turn. She is known to have visited slaughterhouses to study anatomy, and to have observed horse fairs in action (she attended dressed as a man) where she made preparatory drawings.

Building upon what others have discovered

Scientists refer clearly to the discoveries of others when presenting their work. Every respected scientific paper contains a list of such references.

In attempting to create original artwork, don’t be ashamed to study the work of other artists. Do learn from and build upon what others have already discovered: Look with curiosity at the work of great artists – how have they problem-solved? This process can eventually help direct you on your own original creative path.

Careful measuring

If you choose to use measuring techniques in drawing and painting, then they must be used carefully and correctly. Not everyone “gets on with” measuring – some artists focus more on replicating observed shapes (perhaps a more intuitive way of working). That is fine – use whichever technique works best for you.

Measuring (i.e. establishing proportions by holding a pencil in your outstretched arm and measuring off distances) can be incredibly useful but, as it side-steps intuition, this technique risks grave error if it is done badly. In the headlong rush to be creative, holding the pencil skew, having your arm bent, and rushing the measurement can all introduce mistakes. If you choose a measuring technique then have your chosen method clear in your mind, be consistent with it, and be prepared to question and repeat your own measurements.

Perhaps those who like to use measuring techniques are particularly adept at flitting between logical and intuitive way of thinking during their work.

An investigative approach

Fundamental to both art and science is the on-going desire to ask questions and solve problems. This is what keeps an artist’s work interesting. However, it can be tempting to take the easy path of producing images that say the same thing over and again. This might appear to make sense commercially but, in the long run, is it art?

If you’re interested in something, then watch out for it wherever you go and in all conditions. Sketchbooks are useful here. E.g. shadows on human heads(where do they fall, how dark are they, what colour are they?)=> keep looking at people of all types and in different lighting conditions, and keep recording.

Above: Antoine Watteau was fascinated by the structure and character of human heads. He left numerous sheets of studies such as this and take trouble to seek out models of various ages and ethnic backgrounds in making such drawings

Do take note of interesting things and anomalies.

Be sure to stop, observe and think before and in-between drawing/painting.

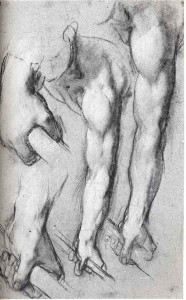

Consider an investigative approach in which you try out different ways of looking at the subject and different options for image-making. Take the example of looking at a figure in a life drawing setting. Part of the model may look as if it is really bearing a lot of weight- what gives it that appearance? If this interests you then don’t be afraid to investigate: Look from different directions; ask the model to shift weight off that area and then load it again and observe carefully –change the lighting and look again– shadows, angles, shapes- what changes?

Above: Federico Barocci study of arms and hands in charcoal and chalk. Here, Barocci used investigative drawing to discover how to portray a man’s arm holding a stick. Between drawings, he must have asked his model to move the arm and grasp the stick again in a slightly different way. Observation of real movement in context can be far more valuable than studying still photographs of posed models.

Has this series of articles on art and science given you food for thought? Feel free to add your opinions by clicking here.

Current and upcoming exhibitions exploring art and science

“Discoveries: Art, Science and Imagination from the University of Cambridge Museums” runs at Two Temple Place, Cambridge, until 27 April

Christopher Benton-Art and Science : mixed media works by a clinical and research MRI radiographer. At Hertford Theatre 6-29 March 2014

Courtyard Arts: Art and Science: Selected from submissions on the theme of art and science. Runs until 29 March 2014 at this Hertford gallery

“Beautiful Science: Picturing Data, Inspiring Insight” runs at the British Library until 26 May 2014

The Art.Science.Gallery in Austin, Texas: Microscopy-inspired work by Katey Berry Furgason is on view until March 23 2014. Watch out for future art-science fusion exhibitions at this specialist gallery.