A Dog’s Place

March 20, 2013

Some thoughts on drawing dogs indoors, with reference to Pierre Bonnard

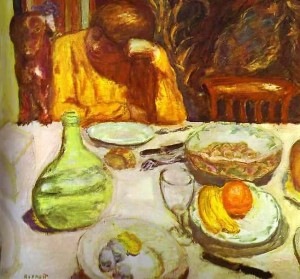

Above: “Carafe, Marthe Bonnard with her dog”, by Pierre Bonnard, c.1912-15. This little dachshund is small but determined. His upright shape will not allow the viewer’s eye to wander out of the left side of this picture.

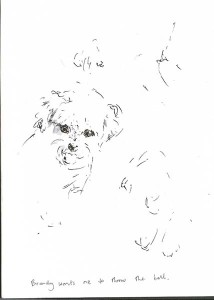

We occasionally have a special house-guest: Brandy the little white dog. She looks something like this:

Above: My pencil sketch of Brandy’s face

Her special talents include ball games and making people smile. I can’t resist sketching her, but this is tricky as she rarely stops for breath. My usual tactic involves holding her ball up in front of her while I draw with the other hand. I do have to throw the ball after a few seconds, and can then repeat the process.

It is just as well that I am not too bothered about drawing fine details or this would become far too frustrating!

Above: Quick pen sketch of Brandy as she waits for me to throw her ball

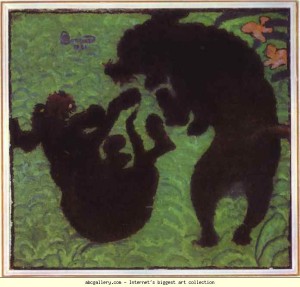

This exercise has had me looking at things in a new way: If the image of the whole little dog is simplified (I try looking at her with my eyes half-closed to get this effect), she could be seen as a pleasing curve-edged shape. Brandy has plenty of Bichon Frise in her breeding, and her body and tail form joyous curves rather like the dog silhouettes in Bonnard’s “Two Poodles”, below:

Above: Pierre Bonnard “Two Poodles”, 1891, oil on canvas. The dogs form delightfully fluid two-dimensional shapes. Green negative spaces between the dogs also form very pleasing shapes.

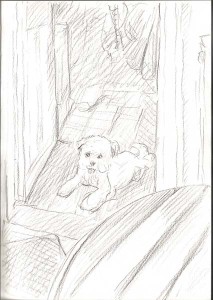

When attempting a silhouette (or flat shape), it is extremely easy to slip into total abstraction (i.e. the shape no longer looks like a dog). On the other hand, when attempting a rapid drawing of a recognisable dog, notice how difficult it is to keep those curvy outlines (see below)! Here I have seen Brandy as a white shape in the doorway and sketched her in that setting. What attracted me to that image was the rather humorous curvy-edged white shape of the dog framed by the rigid lines of the doorway and tiled floor. In my attempt to draw a dog with an identifiable face, body and legs, the curves and some of the humour have been lost:

Above: My attempt to sketch Brandy in the kitchen doorway. The edge of a round, slatted table is in the foreground.

In contrast, look at the sketch below by Pierre Bonnard. He developed his painted compositions from his own sketches. Here we have a dachshund presiding over an overladen table. Bonnard has given the dog, objects and room an excellent sense of three-dimensional space. He has also caught the dog at such an angle that its body, and the negative (background white) shapes around it form pleasing curvy shapes. The resulting image is witty and makes me smile:

Above: Pierre Bonnard sketch of interior with dog

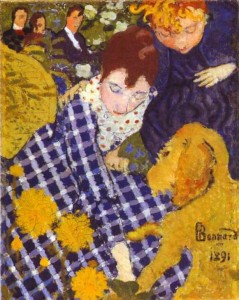

Above: “Woman with Dog” by Pierre Bonnard, 1981. Here is an image of the artist’s sister bending forward towards the family dog. Notice how the dog, and the areas of fabric around it, form pleasing two-dimensional shapes within the composition.

A practical approach to sketching bouncy pets indoors

Here is my preferred approach to drawing a bouncy dog in a room. Sketch the essentials of the room (edges of sofa, rug, etc.) while the dog is otherwise occupied. When the animal does stay still for a moment then draw a fleeting image of them within your sketched interior. It is rather like creating a stage-set, and then placing a character into it.

Why work this way?

Drawing the important parts of the room will give your image a sense of space and structure. This also creates a framework on your page within which you can add a rapid sketch of the pet. Making a point of drawing the room first is also a practical idea because it takes the immediate focus away from the animal. Many pets resent being stared at, and will be more relaxed if you don’t stare fixedly at them as soon as you open your sketchbook!

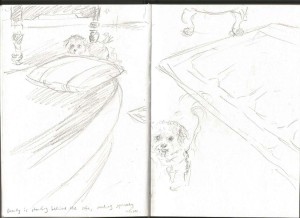

Above and below: My fleeting drawings of Brandy in my lounge. Edges of rug and some furniture have been sketched in first

If the dog is very energetic then there is no opportunity to hold up a pencil for traditional measuring techniques. To check proportions, two other techniques are much quicker: Firstly, check which bits of the room align with the main parts of the dog. Secondly, notice the approximate shapes of “negative” spaces around the dog and scribble these down as best you can. If you’d like me to go into these techniques in more detail then please add to “comments”, below, or contact me here, as this could be the topic of a future blog post.

Above: More quick pencil sketches of Brandy. The writing on the left-hand page says “Brandy is standing behind the sofa making squeaky noises”

My fleeting sketches of Brandy are unimpressive but, through these attempts, I am just starting to see something that interests me and to get it down onto paper. With animals, a pleasing shape as the creature turns, or a momentary glance, may be the whole point of the picture, and is all too easily missed when drawing.

Above: “Greyhound and still life”, 1920-25, by Pierre Bonnard. The dog turns to look hopefully at the delicious food. Not only has the artist captured the turn of the dog’s head, but he has also noticed attractive shapes around the animal and has emphasised these in the finished image.

In summary: Tips for sketching dogs indoors

- Decide what interests you most about your particular dog (e.g. it’s posture, huge bulk or curvy shape) and be sure to get that down in your sketchbook as a priority.

- When time is short, omit all details.

- Look at the dog with your eyes half-closed to help you to see the essential shapes before putting pencil to paper.

- Don’t stare for too long at the dog. They consider it bad doggy etiquette. Blink quite frequently and look away at times.

- When drawing an awake dog, you may need to have two drawings on the go at once as the animal will move from one position to another.

- Include the interior (furniture edges, doorways, etc.) in your image to give your dog a sense of posture, balance and scale.

- Try drawing the interior before you add the dog to the image.

- Photos can perhaps be useful as a record of coat markings, etc. A sense of immediacy and character can be lost in a photo. Try taking a short video of the dog instead. You can always freeze-frame it later.