What is the problem with edges?

April 24, 2012

I’m referring here to the physical boundaries of an object, the “edge” or “contour” of the object between itself and its background. Edges also occur wherever there is a sharp change in plane within a form, even if this would not show up in a silhouette drawing, e.g. the edge of a windowsill, a fold of fabric or the crease across a baby’s wrist.

In real life, what we actually see of an edge depends on how the light falls on it. There is often a difference in tone and perhaps colour between the object and its background, and there is often a pool of shadow either beneath or on both sides of certain edges. Occasionally, an edge may appear as a line of highlight if the light is falling directly on it, e.g. the edge of a mug in sunlight.

We rarely see edges as lines in real life, though in itself this fact doesn’t mean that we must not represent them as lines in our pictures.

Well… I love to draw edges

Drawing the edges of things is a wonderfully direct and simple way to represent them. In our culture, children are taught from infancy to draw objects in this way (to draw an “outline”), then perhaps to colour in as a second stage.

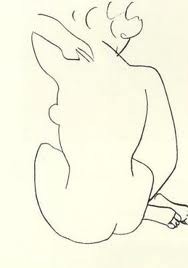

As artists, we consider tone, volume and other aspects of representation, though the potential for emphasis of edges is still seductive. The use of edges can suggest a 3-dimensional form while also creating beautiful 2-dimensional shapes within our picture.

Many artists, myself included, love the process of drawing lines. The great profusion of possible linear media available, from bamboo pens to water-soluble pastel sticks, draws us in yet further…

So what is the problem?

Some potential pitfalls when using linear edges (I have been guilty of all of these):

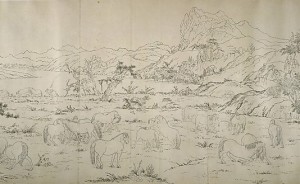

- The edge as visible line rarely exists in nature, so we need to manage our edges in some way to produce a convincing image.

- Edge quality varies depending on the effects of light, so an unvarying line may be inappropriate.

- A solid edge may make the image appear to be “fixed” in space and destroy any suggestion of movement.

- The outline of a thing doesn’t always represent how the weight falls through it and, for that reason, sometimes fails to give the viewer much information.

- The mere outline of a subject does not give much information about its volume in space and can be misleading (e.g. are we looking at a woman or a cardboard cut-out of a woman?)

- A solid unvarying edge sets our image “in stone” as if the artist is saying “this is definitely how I see this thing”. If working in such a way, the artist must get the edges in exactly the right place with exactly correct perspective and foreshortening or the image will look faulty.

- Many edges do not, in real life, mark a change in tone. There may be a pool of shadow on both sides of the edge. This can create a technical problem if the artist attempts to draw an outline first, then shade it in.

- The outer edges of a rounded object represent the parts that are disappearing from view. Perhaps they should be given less emphasis than the centre of the object that bulges towards the viewer.

So should we draw edges as lines or not?

So should we draw edges as lines or not?

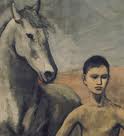

Yes, don’t throw away your favourite pens. If we take the above considerations into account then lines can indeed be used to represent edges. Convincing images are possible, and the lines themselves can be beautiful. For example, look at this drawing by Guercino (1591-1666).

In my “What to do about edges” workshop on Friday 27th April, I shall share plenty of suggestions as to how to make this work. There are different strategies that can be used, depending on the aim of the artist. I am currently gathering together some Old Master pictures to illustrate possible methods of working, and we shall discuss these and apply them to still life drawing. Guercino was a master of meaningful edges, and we can refer to the book, “Guercino Mind to Paper” by Julian Brooks. I am also selecting pictures by Henry Moore, Rembrandt, Leonardo da Vinci, Matisse and Raphael among others.