Art and science: Is there any overlap?

December 16, 2013

Above: Joseph Wright of Derby “An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump”, 1768, oil on canvas

I’m currently furthering my veterinary knowledge in order to specialise in small animal rehabilitation. In addition to fantastic practical sessions, this course has sent me back to the dissection lab, and to the library in search of scientific papers.

With a life split into distinct sections (drawing/painting, scientific study and on-going part-time veterinary work) I started to say, with a smile, “I’ll just put my art hat on” when about to start drawing or, “hang on, I’ll just put my learning hat on” before focusing on the veterinary course.

And then one day when I forgot to take off my “art hat”, I noticed something interesting: My grasp of new scientific ideas seemed more complete, and more satisfying, if I continued to think in an artistic frame of mind.

Why should this be?

Can something of the artistic approach be valuable to the scientist?

Indeed, can something of the scientific approach be of value to the artist?

With current interest in interdisciplinary thinking in the art world (click here, for example, to see details of the new MA in Art and Science run by the University of the Arts, London) these questions deserve more thought.

A very general comparison of the scientific method with the artistic approach

I’ll explain and illustrate these points more fully in my next article but, as an introduction, here is an overview:

What do scientists do?

Scientists notice things (they may note an interesting observation from the natural world, or else a point worthy of investigation resulting from a previous scientific study)

Scientists come up with a question and then a hypothesis.

Scientists perform an experiment or trial in order to test their hypothesis. This testing procedure is very methodical and can, in some cases, be time-consuming and repetitive. Results are recorded carefully.

Scientists analyse their results objectively and come to conclusions.

Scientists present their results and conclusions for others to share (there is a peer-review process prior to publication).

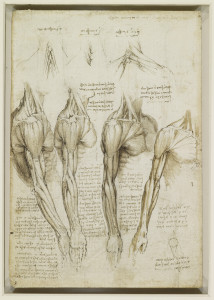

Above: Leonardo da Vinci: “The superficial muscles of the upper extremity from the lateral to the anterior aspect in turning through a right angle”, c. 1510. Leonardo was investigating superficial anatomy as required for artistic representation of the human shoulder. He wrote questions to himself in the text: “What are the muscles which are never hidden either by corpulence or by fleshiness? What are the muscles which are united in men of great strength? What are the muscles which are divided in lean men?”

What about artists? What do artists do?

The artist’s way of going about things is less well-defined, but perhaps has more in common with true scientific methodology than we might have at first thought:

There are of course a great range of artists working in any kind of medium from pencil to video installation, and with approaches that vary tremendously from one another. What do all these people have in common?

Artists notice things (a view shared by Grayson Perry and others)

Artists question and, if necessary, rethink accepted ideas.

Artists present their thoughts for others to share.

The above three sentences sum up what artists do (if you’d like to change my wording, disagree or add to this, then please share your thoughts in the “comments” box, below). These three tasks (noticing, questioning and presentation), are also fundamental to good science.

Do artists perform tests or experiments? Yes, to some extent, but very informally and in a subjective manner. Many artists solve problems through a process of trial and error. This is a kind of valid but unsystematic testing. There are also ways of thinking through an artistic question or problem and working out a solution by making and evaluating a series of preliminary sketches.

Do artists analyse their results? Yes, but this is an extremely subjective evaluation. It may be a matter of self-evaluation, or involve the difficult business of presenting finished work for critique, competition or sale and noticing what other people say about it.

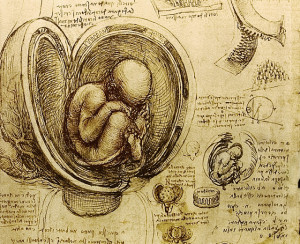

Above: Leonardo da Vinci “The foetus in utero”, c.1510-12. There are actually some errors here in the representation of the anatomical coverings of the human foetus and, in the text, there is the incorrect statement that the heart of this child does not beat. However, this image is remarkable in its empathy. Leonardo drew from (presumably rotting) corpses, yet he shows the foetus as a precious child huddled within its mother. This is entirely relevant to his accompanying text in which he writes about the shared soul of mother and child. Within this text he writes, “…the desires, fears and pains are common to this creature….and a sudden fright kills both mother and child”.

Some other comparisons between artists and scientists

In both art and science, there is a fantastic culture of learning from what others have previously achieved. Artists continually look at old paintings and contemporary work to see how both their peers and the “great masters” solved familiar problems of technique, composition and representation. Scientists read around their subjects of interest, learning from the previous work of others and keeping abreast of current thinking.

Artists and scientists both build upon the work of others. Scientists may repeat someone else’s experiment, or develop a new idea and experiment directly from theirs. In either case, they must explain their thought process and provide a clear reference to the previous scientist’s work when writing their paper. When artists are directly responding to a particular work of an old master, they might title their work, e.g. “…after Rembrandt”. Much more commonly, the influence of the old master on the new piece of work is more vague. Those “in the know” might recognise a similarity of e.g. brush-strokes or colours, but the old master in question need not be formally credited.

There is a horror of plagiarism in both art and science!

Here is a quotation from John Maeda (president of Rhode Island school of design) : “Artists and scientists tend to approach problems with a similar open-mindedness and inquisitiveness — they both do not fear the unknown, preferring leaps to incremental steps” (this is from Scientific American, July 11, 2013, but I have added the highlighting).

Scientists have a great understanding of what is subjective as opposed to objective. Do artists have a similar understanding? It is easy for artists to get caught up in myth and subjective opinion. The evaluation of the work of artists is also very subjective. However, artists have a great understanding of looking at something in the real world objectively. Those who have gone through rigorous life-drawing training know all about illusions caused by foreshortening, and can still understand the model’s structure without being misled by skin tan-lines or reflections.

Further thoughts

Following this introductory overview article, I plan to publish further thoughts on this subject. The next article will explain the scientific method more fully (e.g. what is a hypothesis?) and show how this compares to the artistic process.

Future articles are also planned, entitled “What can artists learn from scientists?”, “What can scientists learn from artists?”, and “Art and science: The sharing of knowledge”.

If you are longing to join in the discussion, then please do add your opinion in the “comments” box below (or alternatively write to me via the contact page if you’d prefer to express an opinion privately).

Error: Contact form not found.