Art and memory: Developing skills

November 7, 2013

Above: Leslie Moffat Ward “Trees near Holdenhurst”, 1913, etching

Some techniques used by artists to develop the application of memory

Approach these “exercises” in a playful, experimental way and in any order that you prefer. They are really mind games rather than true drawing exercises. These methods are primarily designed to change the way that you see and remember. Approach with an open mind, and with plenty of cheap paper at the ready…

1) “Seeing pictures”

This is a technique that you can use anywhere. It is a great boredom-buster at the bus-stop.

Simply look at the scene in front of you, and visualise all or part of it in your mind as a picture composition. To start with, just be aware of this scene as a potential picture while you are still looking at it. Then try looking away from the scene…can you still remember the essentials of the image?

Above: The camera records a view of trees in all its complexity. Simplify the image by considering it as a group of dark-toned shapes against a light sky. You may also want to remember the horizontal strip of light across the distant edge of the lawn.

What is the point of the “seeing pictures” mind game?

This really is just a mind game. It is primarily useful in increasing our conscious awareness of what we are seeing. By trying to commit the scene to memory, we initially have to select what has greatest importance to us (e.g. bold shapes and tones as opposed to fiddly details). Such a selection process is key for many artists. In addition, attempting to remember visual images can, over time, improve memory skills.

“Seeing pictures” also helps us to make the mental switch from looking at the world around us, to portraying something of that world on a (usually rectangular) piece of paper.

Tips:

Most pictures are rectangular, so you may wish to think of the image in a rectangular (landscape or portrait-style) format. You could hold up a cardboard viewfinder to view the scene within a rectangular frame, or without a viewfinder you may be able to mentally “crop” the image, so that you are just considering a rectangular section of it.

Good scenes to start with are simple ones with strong tonal contrasts, e.g. trees silhouetted against the sky.

Don’t try to be a camera! Remembering detail is not necessary. Attempt to remember some or all of the following “essentials”:

Simple tones (very dark, very light and somewhere in-between)- e.g. dark trees against a light sky

Simple shapes – e,g. the shapes of trees massed together, and the shape of the sky around those trees.

Any movement– e.g. are the trees being blown one way or the other by wind?

and perhaps, broad areas of warm vs. cool colour

Though you are not trying to be a camera, you can effectively “zoom in” to the scene to visualise a rectangular image of just a small part of your view, if you wish. You could achieve this by holding the cardboard viewfinder further away from your eyes, if you are using one.

Above: Any part of the view could be considered as a potential picture. Here is a section of tree canopy selected from the previous image. How would you go about memorising this? Consider the shapes of canopy “clumps” (rounded, perhaps like bunches of grapes), and of the negative shapes of sky between the leaves and branches.

There are different ways to remember a scene. Experiment and see what works best for you:

1) You may intuitively remember a bold shape in the scene by simply focusing on the shape and memorising it.

2) A shape may remind you of something else. For example, a complicated space between tree branches might look, to you, like a pair of frantically-running legs. Remembering the image of running legs may later help you to recall the shape of the gap between branches.

3) Or you could take more of a logical approach. For the example of trees against the sky within an imagined rectangular “frame”, consider the most important proportions within the image. Would the trees reach the top of the image, or come perhaps just halfway up, or three-quarters of the way up the picture? How far do the trees reach across the image sideways? Is the mass of trees taller than it is wide, or vice-versa? Are the main trunks of the trees vertical? If not then how much do they tip and in which direction?

Developing this idea further:

a) Remembering moving images.

Once you get confident with this visualisation trick, then try it when the scene is moving past you, e.g. as seen from the window of the bus or perhaps, out in the countryside, from the back of a horse. Camera analogies are unavoidable here… Can you remember a “snapshot” image of a simple scene? How much is the human mind capable of in this regard?

A note about cameras:

I advise against taking a camera snapshot to back up your visual memory unless you really know what you are doing. Most photos capture super-human detail, but subtly distort the essentials of the image, i.e. the tonal gradation and the field of view. For capturing essentials, your eyes and brain are generally better than the camera.

On the other hand, we can learn from the great photographers who are truly aware of what they see. In the words of Henri Cartier-Bresson, “…one has to feel oneself involved in what he frames through the viewfinder. This attitude requires concentration, a discipline of mind, sensitivity, and a sense of geometry. It is by great economy that one arrives at simplicity of expression.”

b) Thumbnail sketch of a remembered image

For a simple scene that is not moving, try visualising as a picture format as described above, and then turning around and making an immediate thumbnail sketch of the remembered image. For a thumbnail sketch, start by using pen or pencil to draw a rectangle in your sketchbook. The rectangle should be of similar proportions to your imagined picture. Draw in what you can remember of the scene starting with the boldest shapes. You could hatch or block in areas of tone with a soft pencil or broad pen.

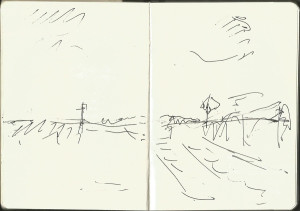

Above: From my position in a car park, I could see interesting shapes in the tops of hedges and trees. I attempted to memorise a section, then turned around and made a thumbnail sketch. Here are three rather scribbly thumbnail sketches resulting from repeating the process with different parts of the view. This is just a learning process. I do not plan to develop the images further.

c) Sketching after visualising

Or, after visualising the image in your head, try making an immediate very quick drawing in your sketchbook while still looking at the scene. Include only the essential broad shapes, directional lines, tones or colours.

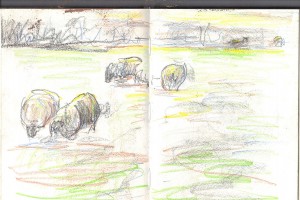

Above: I happened to have a few coloured pencils to hand when I drove past this group of sheep late on an autumn day. What struck me from the car was the appearance of the sheep as rounded masses, with yellowish sun slanting over their backs. In stopping the car and making a scribbly sketch, this was all that I attempted to convey on paper.

d) Sketching moving images

Have a go at drawing views from the window when you are on a moving train. Again, just focus on the very basics. There may be a bold shape of land beneath a block of sky, perhaps with a shape suggesting a line of trees or buildings.

Above: In a pocket-size sketchbook, here is one of many views from a moving train

2) Sketchbook experiments

Above: Edouard Manet pen and ink sketch of La Rue Mosnet, c.1878

Like Toulouse-Lautrec or the young Matisse, take a sketchbook and draw people out and about. Avoid including much detail. Basic silhouetted shapes are a good start. Important things to note with figures include:

-

Is the torso upright or tipped?

-

In which direction is the figure looking?

-

Considering the person in their clothes as a single “mass”, what basic shape are you looking at?

-

Are the legs and feet out at an angle, or are they directly under the head?

-

The simple silhouetted shape of the head, neck and shoulders tells us plenty about character and identity, as described further here.

Above: A sketch of a man waiting to be served at a café. This was simply an attempt to capture his posture on the page.

Using a sketchbook in this way makes us look and then record what we see in the most direct way possible. It also allows us to experiment with that curious natural ability that humans have of being able to look at something, perhaps from a distance and in poor light, and “knowing” immediately what it is.

For example, you might see a child with their head turned away from you. Even from a distance, you would recognise this figure as a child. You may have a good idea as to whether it is a boy or girl, their age and even some idea of how they are feeling. But can you sketch the child’s figure in this position in any meaningful way? If not then why not? What is it that you are seeing, and how can that be transferred to the paper? Experiment with different drawing approaches to discover what is most useful, e.g. flat tone, hatched lines, simple outlines.

There is a current vogue for beautifully-finished artist’s “sketchbooks”, completed as publishable journals. My suggestion is to use a working sketchbook in a more experimental way, and not to mind if many of the drawings are scribbly, “sketchy!” or even incomprehensible.

3) Drawing a dream

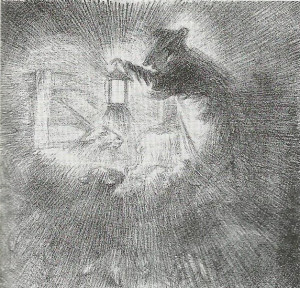

Above: Charles Hazelwood Shannon “Shepherd in a Mist”, 1892, lithograph

For those who wish to link art in with emotion and memory, dreams have great potential.

The memory of a dream may be curiously incomplete and fleeting. We are sometimes left with a strong emotional memory on awaking, as if we have actually lived through a new experience.

Do you ever remember your dreams? If so, is this a visual memory? Like a fascinating piece of art, the initial visual memory of a dream may seem to be shadowy, incomplete, perhaps comprised merely of odd glimpses, while still representing a strong emotion.

Try this:

- You can only do this “exercise” on waking from a dream. Try keeping a notebook or sketchbook by the bed, as any visual memory of the dream will alter within minutes.

- As soon as you wake, note down anything that you remember from the dream. Use a combination of simple drawings and words.

- Be honest with yourself as to what you remember seeing in the dream. For example, the dream might have centred on a friend of yours, but perhaps you only remember seeing them as a shadowy shape. In your notebook, draw the shadowy shape rather than “making up” a drawing of the friend. Your notebook drawing may appear rather abstract. That is still interesting and valuable.

- If you don’t have the time, skill or media to convey the image fully as an immediate sketch in the notebook, then add words to further describe what you remember. For example: Which way was the friend looking? Were they moving?

- If the dream involved a sequence of events, then is it best conveyed as a series of drawings like a storyboard, or do you just remember odd glimpses here and there? Again, be honest with yourself as to what you remember.

Taking the idea further:

A collection of visual and written notes about dreams is fascinating in itself. In recording dreams, you can learn something of how emotion ties in with visual experience and visual memory. That is what art is all about.

It is not essential to develop any of the notebook images into finished pieces of art, but there is plenty of potential to do so if you wish. Whether you work towards producing an abstract or representational image, take care to include your genuine visual memories of the dream rather than constructing new images based on the dream’s story. The remembered images may well be shadowy, incomplete and ambiguous.

Above: An example of an image developed directly from a dream. Having dreamt about my old dog having a conversation with me (!), the resulting visual memory was of the front part of my old dog’s face. In my immediate sketchbook image, the animal’s mouth was closed and still as I remembered it from the dream. Without that initial sketch, I would have assumed that a talking dog would have a moving mouth. The dark areas with no form or detail were also remembered, and struck me as curious when I woke up. This charcoal drawing was later drawn using the sketchbook image and notes..

4) Drawing something that gives you an emotional reaction

What, in your life, gives you an emotional reaction when you look at it? Perhaps it is the face of someone dear to you? Perhaps your pet or favourite possession? If that feeling is important to you then play with “banking it” within your memory (i.e. deliberately remembering it).

When you look at this person or thing, then what exactly do you see that triggers the emotional reaction?

For example, if it was a person, then consider whether it was the shape of their face (as is so often involved in recognising someone from across a room) or perhaps the texture of their hair or skin, the shape of the top of their head (a common emotion-trigger when a parent looks at a tiny child) or something about their posture or gaze.

Now…can you “visualise” something essential that you have remembered of that person or object in your mind?

If so, then that is an excellent start.

Above: David Bomberg “Self portrait with a pipe”, 1932, oils. Under many lighting conditions, we see a series of characteristic light and dark shapes when we look at someone’s face. The shapes of the eye sockets , forehead and shoulders tell us plenty about the person’s identity and character.

You could then develop the eyes-brain-emotion-memory skill by exploring your surroundings further. There may be far more mundane objects that induce some kind of fleeting emotional reaction in you, whether positive or negative.

You might, for example, look at a section of peeling wallpaper and feel anger or frustration. Again, store the exact emotion in your “memory bank” (that does not mean that you need to be left feeling angry or frustrated for the rest of the day). What did you see of the object that brought on that emotional response? In the case of the peeling wallpaper, it might be the shape of the exposed wall, or the texture of the wallpaper edge, or perhaps something of the colour of the paper.

Taking this idea further:

Try drawing the person or object, taking care to include whatever factor triggered your emotional response. So, for example, you may feel happy when you spot your dear friend across the room, and perhaps you have decided that it is the exact shape of their face that triggers your emotion. Try drawing them, paying careful attention to that shape. A blocky tonal approach in soft pencil or charcoal may be good in this case.

Approach this drawing “exercise” in a very experimental way. You may find that your initial drawings are rather meaningless. Why do these early drawings not trigger the same emotional response as you experience when looking at the person “in the flesh”? Try different drawing approaches in various media and see what works best.