The essence of an object: the role of memory

October 19, 2013

How does memory tie in with the creation of art?

A quick internet search for “memory & art” directs me to websites in which events or people are commemorated in painting, sculpture and other media. Further searching leads me to information on those who use childhood memories to create highly imaginative and unusual work. Drawing from life can also be used to record fleeting memories, and it is interesting how many sketchbook addicts (myself included) claim to use drawing to back up an insufficient memory.

Above: Odille Redon “Pegasus Captive”, 1889, lithograph

What about the artist who sets about painting a still life or portrait? Is memory required for such a process?

To go through the mechanics of drawing a portrait does not require human memory. For example, take a look at the drawing robot. But artists are generally after something more than that. In order to create interesting work that can truly be described as art, perhaps the ability to process memory is essential …

…I’ll let you read on and come to your own conclusions.

“Drawing is remembering”

Once again, I am turning to Henri Matisse for ideas, mainly because he left a wealth of written and spoken information on the subject. Here I am referring to the excellent text of John Elderfield’s “The Drawings of Henri Matisse”.

Elderfield described how the young Matisse would go out with his fellow student Marquet to sketch in the streets of Paris. They attempted to draw silhouettes of people moving in the street. In Matisse’s words: “We were trying…to discipline our line. We were forcing ourselves to discover quickly what was characteristic in a gesture, an attitude.”

Above: Sketches of people and dogs drawn from life, this time by Toulouse-Lautrec. There is plenty of information here about posture and character. In particular, look at the shapes between and around the two dogs.

Attempting to draw moving figures is a real challenge, especially if the subject moves before the artist’s pen touches the paper. Elderfield writes, “sketching in the street…made it evident to Matisse that drawing was indeed not only a matter of observation but of memory: of recording, in fact, not what was seen “out there”…rather, what had been stamped in the mind. The act of drawing was that of remembering.”

Have you tried to draw people or animals who are continuously moving? When I have forced myself to draw, for example, equestrian vaulters on a cantering horse, I have struggled to come up with a meaningful image. To produce a drawing that is representative of the moving subject is a mental challenge that involves looking and thinking and a keen short-term memory for the essentials. A prior knowledge of the subject and a longer term memory is of course also helpful here.

Above: Some of my sketchbook attempts to capture poses of equestrian vaulters in action.

“My painting is finished when I rejoin the first emotion that sparked it”¹

So said Matisse. And he also gave great importance to remembering the initial spark of emotion that came at the beginning of the painting. Matisse wrote of looking at the subject (e.g. still life or figure) with an open mind and really observing the subject in a concentrated way. “..The subject is experienced, and drawing is the record of that experience, of the unconscious sensations which sprang from the model.”

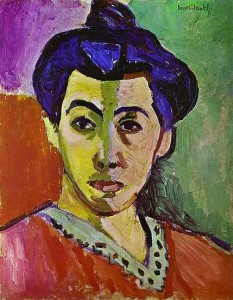

Above: Henri Matisse “The Green Stripe”, a portrait in oils of his wife, Amélie Noellie Matisse-Parayre, 1905

There is no point in trying to record the ever-changing present while it is taking place, as life goes on and the subject alters, as does the artist’s response to it. Even when drawing a “static” professional model or a pot plant, there are tiny changes over time. Consider changes in the lighting, the mood, and your (the artist’s) response to the subject.

Matisse believed that, instead, the artist must preserve the memory of the first concentrated observation. Elderfield interpreted Matisses’s outlook as follows: “To remember the first unconscious sensations which sprang from the model is to make a drawing”.

Rediscovering reality

In creating a drawing or painting, the artist may work up to a point at which their image starts to coincide with a recent or much more distant memory. They may think back to the initial “spark” of emotion of that day’s work. Alternatively, something about the image may start to resemble some other memory, recent or distant, within the artist’s mind.

Above: Pierre Bonnard “The Lunch of the Little Ones”, 1897

Proust wrote of “the grandeur of real art” involving the rediscovering of a reality that is “a certain relationship between sensations and memories which surround us at the same time”.

Is this fanciful?

No…. In going about our daily business (making breakfast, walking through the street, etc.) we are surrounded by all kinds of sensations and memories, both conscious and subconscious. As we walk through the street, we are not only aware of the pavement ahead , but also of surrounding buildings and people. Even if we are paying no direct attention to architecture, we are still certainly aware of being surrounded by, say, looming skyscrapers as opposed to neat residential houses. There may also be noise, perhaps traffic, birdsong or chattering people.

In addition, our head and eyes are continuously moving as we walk. Unlike a smoothly-gliding video tracking system, our eyes glance about all over the place, catching a glimpse of this here and of that there. We need some kind of very short-term memory system just to make sense of this. There might be a glimpse of the kerb, a flash of a car going by, a recognised face in the crowd, the brief sight of a cake in a shop window and also of our own feet as we step on the pavement. Much of this is mundane and quickly-forgotten. The occasional image (a girl in the street, a hat in a shop window) or combination of images may trigger a new emotion or distant memory. That is part of the human experience.

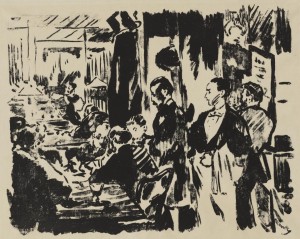

Above: Edouard Manet “At the café”, 1874, gillotage on beige wove paper. This complex image of a crowded room is simplified into rhythmic lines and strong shapes. Angles of heads are essential here, as are shapes of spaces between people. With a minimum of detail, Manet shares with us (across the centuries) the atmosphere of this noisy café.

Painting from memory

Henri Matisse said that he painted “from memory”. Numerous drawings made prior to a painting were created, not as first draughts, but to gain a deeper understanding of his subject. He wanted to know objects thoroughly before attempting to paint them: “Deep within himself…[the artist] must have a real memory of the object and of the reactions it produces in his mind”.

Matisse certainly did not transpose his drawings to a canvas in order to make a painting. He claimed not to be satisfied with a mere enlargement. Whether he used his drawings for close reference, or just put them to one side and truly painted “from memory”, I am not sure.

How can we use these ideas in practice?

The techniques and craft of painting can be learned, but what about the artistic, intuitive aspects? Is it possible, for example, to learn to improve our awareness and application of memory in drawing and painting?

Yes, certainly, with some careful thought and application, though it is a gradual process.

In my next article, I shall share practical suggestions on how to go about this using a series of mind games and simple drawing exercises.

1) Quoted by Pierre Schneider within “The Bonheur de vivre: A Theme and its Variations” lecture at MOMA, New York, 30 Mar 1976