How to draw horse eyes part (3): Expression and mood

September 29, 2012

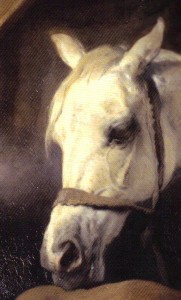

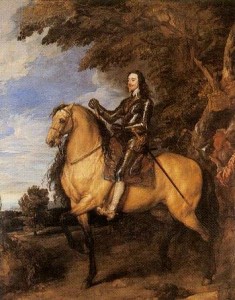

Above: Detail from “Equestrian portrait of Charles I” by Anthony Van Dyck, c1637-8

Some thoughts on horse eye expression for artists

To complete my thread on eyes for equestrian artists, here are some thoughts on eye expression. As any horse handler knows, the mood of a horse can be undertood from their body language. Eye expression does come into this but, in reality, other aspects of horse body language may be more important. Head carriage, ear position, tension around the nose and mouth, and general muscle tone all have very important parts to play. However, when a person (lay person or experienced horse handler) looks at a piece of equestrian art, the expression in the horse’s eyes is of great importance. Controlling that expression can give you, the artist, a great tool for managing the emotion and drama within your picture.

PLEASE NOTE: The ideas in this post relate to how horses appear in pictures. This article is written for artists and for those who enjoy looking at equestrian art. This is not a tutorial on how to judge a horse’s true character from its appearance. For that, you would really need more emphasis on the rest of the horse’s body language.

Above: Detail from “Whistlejacket” by George Stubbs, 1762

In this post, I shall go through various horse eye expressions that have been used in famous paintings. What we are really looking at is the amount of muscle tone around the eye.

When the horse appears relaxed, calm, sleepy, friendly or kind, the muscles around the eyes are softer, with less well-defined edges.

When the horse is alert, apprehensive, angry, crazy or frightened, the muscles around the eye become more tense and have very well-defined edges.

The worried expression

Typically, a worried horse has tense muscles around the eyes. This can have the following effects:

- Well-defined eyebrow muscles above the eye in the shape of an upside-down U or V.

- If the eyebrow has become an upside-down V shape, there may be an obvious pointy shadow under its peak.

- Upper eyelid pulled back a little so that the eyeball becomes a little more prominent.

- A narrow band of the white of the eye “sclera” may show at the top or outer corner of the eye (because the eyelids are pulled back)

- Obvious wedge-shaped or curved highlights in the top half of the eyeball.

The above effects are more prominent in certain breeds of horses ,e.g. Thoroughbreds, who naturally have more muscle tone around their eyes even when they are relaxed. Below is the handsome head of Ted, which I have included here as it illustrates the upside-down V eyebrow. This photo shows him having just been put in a box on an unfamiliar yard so he is feeling a little apprehensive. Ted’s breeding and lean conformation make those peaked eyebrows really stand out. I have labelled the eyebrow, “V”, and the deep temporal fossa, “T”. You may wish to click on the image to better view the labelling and detail:

Above: A Warmblood, “Ted”, looking a little apprehensive

The fearful eye

To create a frightened eye expression, just follow the above list for a worried eye but take everything to a greater extreme.

For example, take a look at the horse ridden by Charles I in the equestrian portrait by Anthony van Dyck, below. A close-up of this horse’s head is at the top of this article. The upper lid is drawn back revealing the white of the eye and a dramatic highlight over the eye surface. This makes the horse look worried, difficult to control and liable to “spook” or take off at any moment.

Above: “Equestrian portrait of Charles I” by Anthony Van Dyck, c1637-8

This is a bit of propaganda…van Dyck was court painter to Charles I from 1632 and was known for his skill at creating glamorous images of his sitters. The king mounted on this horse was painted as a calm and unflustered figure. In giving the horse the appearance of a creature who is difficult to control, van Dyck makes the rider, Charles I, appear to be a masterful horseman.

The terrified eye

How do we show a horse that is truly terrified? The worry signs listed above can all be included. In addition, the eyes may be fixed rather oddly on something. See how the terrified horse, below, is staring so intently ahead that the dark pupil and iris are pulled forward, and the white of the eye is visible behind them. In other cases, a terrified horse might stare at something that is out at the side or behind it, perhaps while turning and running in the other direction.

Above: Detail from “A Horse Frightened by Lightning” by Théodore Géricault, 1817

The angry horse

It is difficult to find photos of really angry horses. I know that their face muscles are supposed to tense right up, with ears pinned back and a tense neck. But what of their eyes? The upsetting painting of two fighting horses by John Wooton, detail below, ticks all factors on my list for a worried eye, but also emphasises the red colour at the inner corner of the eye. In the complete image, this grey horse is facing down another angry stallion. How realistic this is, I’m not sure, but the emotion in the painting is convincing:

Above: Detail from “Two Stallions Fighting” by John Wooton, 1733-6

The intelligent and compassionate horse

There is a way of making horses’ eyes appear to be intelligent and compassionate. This has nothing to do with reading real-life horse-expressions but may be more of an anthropomorphic fantasy. It is an expression that is understood by the viewer of a picture rather than by a horse-handler at the stable.

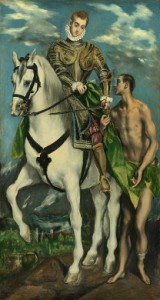

I am thinking here of the horse in “Saint Martin and the Beggar” by El Greco. In the full picture, the wealthy officer mounted on the horse does a good deed in donating part of his cloak to the naked beggar on the ground below. However, the expression on the officer’s face seems rather detached to me. He is doing a good deed, but is perhaps not really reaching out emotionally to the beggar (am I being fair here?) But El Greco has given the horse an expression of great concern and compassion. There seems to be an emotional connection between the horse and the beggar in this picture. (This was mentioned in a previous article in relation to their legs. If you are curious then click the link here and then scroll to the bottom of that page).

Above: “St Martin and the Beggar” by El Greco, 1597-9. Below: horse head detail from the same painting

Features of an intelligent and compassionate eye expression:

-

Clear peaked eyebrow (an upside-down V shape)

- Upper lid is not raised, so a fringe of upper eyelashes may be visible.

- Highlight on eye surface is small and not over-emphasised

- Subtle skin wrinkles around eyes may be visible

This really creates a parody of a human “worried” expression, with raised brow and lowered upper lids. El Greco knew his anatomy and was not afraid to distort it in order to get his point across.

Some relaxed horses have worried-looking eyes

The eyes of some finely-bred horses show some of the hallmarks of a “worried expression” even when the horse is completely relaxed. Take the example of San Real, below. He has an obvious upside-down “V” of an eyebrow and sometimes quite a pronounced highlight across the eye. This eye expression could be interpreted as worried or frightened, though at the time that this photo was taken, he was happy and relaxed (and was rather hoping that I might have an edible treat in my pocket).

Above: San Real, Dutch Warmblood owned by Tina Layton of Contessa Riding Centre

If painting a horse such as San Real, the artist can include those well-defined muscles around the eyes, but should first make the decision as to whether to give the eyes a “highly-strung, worried” appearance, or alternatively whether to make them look “intelligent and thoughtful”. Spending some time with the horse and owner should give you some idea as to what would be most appropriate in each instance.

Sometimes a pale iris can, to the lay person, suggest a staring, frightened eye. Take the case of Max, below:

Max has blue eyes with beautiful black pigment around the lids. I took the photo just as the blacksmith started to work on him so he was, perhaps, a little apprehensive. However, it is the pale eyes and the dark “eyeliner” that gives this image a startled look. The upper lid is slightly raised, with a little creasing of the eyebrow above, but this is not a horse who is panicking. The true white of the eye is not visible at all. What we are seeing is the pale blue iris.

Look at his fairly relaxed head carriage, etc. in the next shot:

Kind, caring eyes

As a general rule, the muscles around the eyes do soften when the horse is in a kind mood (San Real, above, may be an exception to this). To call a horse eye expression “caring” may be a bit of fantasy, but some horses in paintings do give this impression. See the gentle face of the Arab horse mum in Edwin Landseer’s “The Arab Tent”, below. She’s in the process of nuzzling her foal here:

Above: Detail from Edwin Landseer’s “The Arab Tent”, 1866

What gives horse eyes a kind expression?

-

a soft roundness of the upper lid and eyebrow

-

soft-edged highlight(s) over the mid to lower part of the eye

-

or no visible highlights, as the upper lid and lashes shade the eye

-

Sight blurring to boundary of eye, as lower lid is soft and is not pulled into a rigid edge

-

typically, a dark colour within the eye

-

Upper eyelashes clearly visible as a fringe

People may describe the eye expression as “soft” or “melting”.

And what gives horse eyes a caring expression?

- All of the above (under “kind” expression)

- Plus just a hint of creasing of the eyebrow and/or upper lid.

Some Andalusian horses, in particular, appear to have a gentle eye expression.

Above: Commodin, Andalusian stallion owned by Shelley Liddell

These eyes can remain “soft” during all kinds of playful, energetic antics. Take a look at Commodin jumping about, below. The drama of this lovely photo comes from the horse’s position angled across the shot, and from its flying mane. It is not always necessary to draw a leaping horse with a crazy eye expression. Here the eyes remain quite relaxed despite the horse’s behaviour:

The “smiling” eye

Now I shall stray further from horsemanship and towards pictorial fantasy. Take a look at the beautiful horse, Romeo below, with his owner. They have trained and competed together, and some of this must be hard work, but here they are sharing a quiet moment in the stable. Romeo is so relaxed and happy that he hasn’t even stood up. There is something on this horse’s face that I read as a “smile”, and it has something to do with the almond shape of the eye:

Above: Romeo and Judith, showing a “smiling eye”

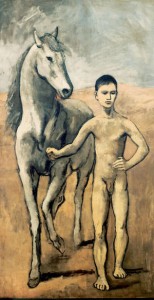

The expression on Romeo’s face, above, reminds me of the horse in Picasso’s “Boy leading a horse”. Here again, the horse and human are sharing a quiet moment of companionship. Like El Greco, Picasso knew a whole lot about anatomy but was also happy to stray away from it to make his point. The eye on Picasso’s horse, here, is little more than a symbolic almond-shaped mark, but I read this horse’s expression as contented and companionable.

Above: “Boy leading a Horse” by Pablo Picasso, 1906

The sleepy eye

If you are drawing a horse from life at close quarters, you will probably find that he or she fidgets for a while. When at last the horse relaxes and stays still for you, the expression on its face may have become unflaterringly drowsy. The head may start to droop and the upper eyelid half-close, so that the eyelashes obscure most of the eye. This is one drawback of sketching horses from life. Unless you want your finished drawing to have a drowsy appearance, you may need to do several rapid sketches from different angles and take a few reference photos before returning to the studio to make a finished drawing.

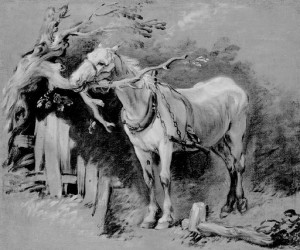

Few great equestrian pictures show a sleepy horse, but here is a drawing by Gainsborough, which may have been a preparatory sketch for his painting “Landscape with Peasants and Horses”:

Above: “An Old Horse” by Thomas Gainsborough, c1755

A stolid, dependable expression

Below is a photo of Caramac, a pony who I used to ride regularly. This picture brings back fond memories of him being a trustworthy, kind chap. There are no worried crinkles and creases around this eye, no apprehensive raised brow or sentimental doe-eyed appearance. I remember once, when riding him nicely forward in the arena, my clothing somehow got caught on the fence. Caramac stopped with no fuss, waited for me to sort myself out, then started off again without complaint. A different photo could well have caught him with a different eye expression, but this image reminds me of his trustworthy character.

Above: Caramac the pony

What makes a horse eye appear dependable and reliable?

- Rounded brow with minimal creasing

- Eye open enough to be alert, but not enough for the white of the eye to be visible

- If a highlight is visible in the upper part of the eye, it fades out just below the upper lid

Note that this the typical appearance of many British native ponies. It is up to the artist either to emphasise this, or to pick out some other character feature, when painting the horse.

A thought on eye shape and composition

Throughout this series of eye articles, I have got rather caught up in detail. We should, however, always remember the overall composition of the picture. Here I must mention the glowing painting, “Arab horseman giving a signal” by Delacroix. This picture is all movement and sharp angles, from the lively little Arab horse, to the rider’s billowing cloak and waving arm. The horse’s eye forms a triangle, and this shape is echoed around and about the picture. The ear and nostril are basically triangles. There are triangle-shaped gaps under the horse’s jaw and beneath the cloak, which itself forms a red triangle. The viewer’s eye is led from the horse’s eye and then around and about the whole energetic image:

Above: “Arab horseman giving a signal” by Eugene Delacroix, 1851

Summary

When a person looks at a picture of a human or animal, they usually try to understand character from the eyes.

Horses have complex personalities. When drawing a portrait, choose which aspect of their character you wish to emphasise.

As horses become more alert or worried, the muscles around the eyes become more tense.

As horses relax, the muscles around the eye become softer.

In the end, the eye is just part of the picture. Remember to check the rest of the horse’s body language, and also to pay attention to the composition as a whole.

Comments and discussion are always welcome

Much of what I have discussed here is very subjective. You are welcome to post a comment with your own views on horse eye expressions which may differ from mine. Please keep within the subject though… this article only addresses horse eyes, not the rest of their body language.

I have not covered “cheeky” eye expression, but imagine that this involves a bright highlight in the eye, and perhaps a look off to one side. When this occurs, I usually seem to be sitting on the horse and so don’t manage to get a photo! If anyone has photos of this or other expressions then do please get in touch.

If you have enjoyed this post then you may be interested in the first two articles in the series. Here are clickable links:

How to draw horse eyes part (1): General structure and position of the eyes

How to draw horse eyes part (2): Close-up detail