More lovely horse anatomy: The rear view

May 9, 2012

Tips on drawing the back end of the horse, with reference to paintings by Great Masters

If, when drawing a horse, you find yourself positioned behind it, you have not drawn a short straw. The rear of the horse is full of design possibilities. You have the great masses of muscle ready to propel the animal forward and, below, the structure of the bones and tendons of the back legs is easily visible even in a thick-set horse.

Look at these powerful compositions, “The Rear View” by Peter. P. Rubens ( below) , and “Horse Market, Five Horses at the Stake” by Theodore Gericault (above).

Let’s first consider how to draw the muscular rump of the horse. The muscles of the rear end drape over the bones of the pelvis. This gives the rump a recognisable shape with left and right sides mirroring one another.

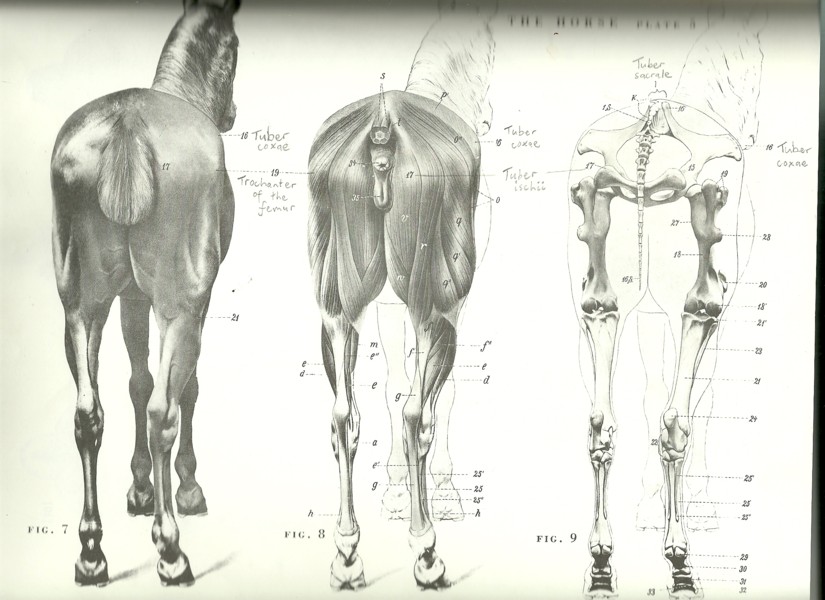

Diagram from “An Atlas of Animal Anatomy for Artists”

My favourite anatomy book is “An Atlas of Animal Anatomy for Artists” by W.Ellenberger, H.Dittrich and H.Baum. I have the 2nd edition which was published in 1956. It covers the horse, dog, cow and lion, with a few oddities in the appendix. I just wish that I had come across this book years ago when studying veterinary medicine as I find these diagrams more pleasing to look at, clearer and easier to relate to living animals than the standard vet anatomy diagrams (and the lion would have been a good distraction). Here is one plate from this book (the pencil scrawl is my own):

The above drawings show three representations of the rear view of the horse. On the right hand side is the bony skeleton. The middle drawing shows how the muscles fit over the bones. On the left we see the rear of the horse complete with skin. Even in this drawing, it is possible to appreciate the direction and shape of the muscles, and to see how these are attached to or stretched over prominent bones.

Deciding where the horse’s midline is positioned

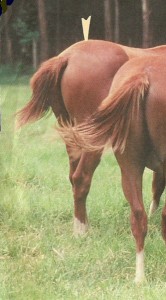

In drawing the horse from the rear end, the first thing to be aware of is where the midline is positioned. Some horses have a coat marking (a “dorsal stripe”) over the spine leading back to the tail, as if just to help artists:

If not, then you just have to imagine a line in this position. The two sides of the rump should be symmetrical on either side of this line which means, from almost every viewpoint, the artist needs to take special care with foreshortening.

Considering the overall shape of the rump

Although the silhouette of the rump is curved from every viewpoint, it cannot really be simplified down to a sphere or into two hemispheres. The rump is taller than it is wide, and rather slab-sided. It helps to be aware of the most prominent “landmarks”:

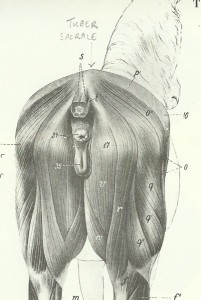

The highest point is the tuber sacrale:

I have marked this high point (the tuber sacrale) on the diagram on the left. If you scroll up to the diagram of the 3 horse rear views, you will see it also marked on the skeleton quite far forward where the pelvis attaches to the spine.

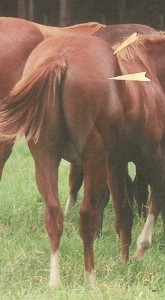

In the photo on the right, I have marked the position of the tuber sacrale with a cream arrowhead. See how the rump slopes down from here back to the base of the tail.

Widest points of the rump

On each side of the horse’s rear, two wide points are the tuber coxae (further forward) and the greater trochanter of the femur (further back). In the photo below, I have used cream arrowheads to mark the positions of the greater trochanters of the femur. This trochanter is simply a knobbly bump on the outside surface of the thigh bone.

Position of greater trochanter and tuber coxa marked on a photo

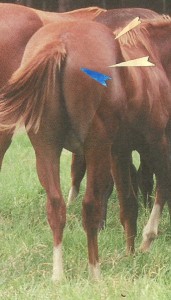

In the photo, below, I’ve marked the greater trochanter again with a cream arrowhead and, above this in the photo, I’ve marked the tuber coxa with another arrowhead.

From some angles, it can help to think of an imaginary line running from the tuber coxa and angling slightly down and back to the greater trochanter. This imagined line marks a change of plane over the horse’s rump.

The point furthest back on each side is the tuber ischium

In the next photo, I’ve highlighted the final “landmark” with a blue arrowhead. This is the tuber ischium. There is one of these on either side of the tail, and they just out at the back of the pelvis. These three “landmarks” define the edge of a slab-like surface at the top of the rump.

Planes resulting in tonal change over the rump

Now take a look at the same photo without the arrowheads and see how the sunlight reaches the slab-like top of the rump in a patch bounded by those three landmarks:

Planar modelling and design possibilities

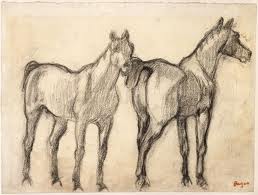

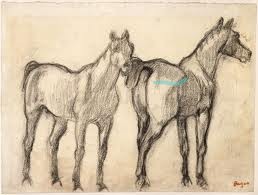

This change of plane over the rump has been exploited by artists for its design possibilities. Here is a drawing by Degas (Two Standing Horses, below left) showing the intriguing change in appearance of the rump when seen from different angles. On the right, I have shown the picture again, having marked an approximate line from the tuber ischii to the greater trochanter to the tuber coxa, so that you can see how this fits in with Degas’ strong planar modelling of the horse:

In Gericault’s “Horse Market: Five Horses at the Stake”, below, we see again how the anatomy of the rump has been emphasised. The bony landmarks are quite obvious in the right-hand horse, in which they create an illuminated oblong that is important within the composition.

The slight hollow down the side of the thigh

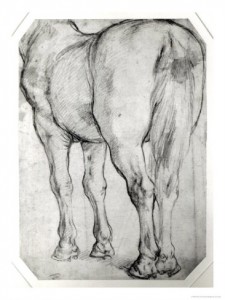

Under the tuber coxa to greater trochanter line, there is a slight concave valley down the side of the thigh. Take a look at this rear view drawing by Leonardo da Vinci, one of his preparatory drawings for the Sforza monument. The edges of the rump are shown by a series of elegant curves. My light pink arrowhead points to the concave “valley” down the side of the thigh.

Those of you who come along to the equestrian life drawing day on Sunday should have the chance to lay your hands on the horse and feel where the important bones are positioned, which sections are concave and which are convex. This will help you to understand the structure of what you are seeing.

Don’t forget to check back here on Saturday as I shall post some thoughts on drawing the lower parts of the hind limbs.