Sketchbook dog drawings

May 24, 2012

Ideas and tips for sketching your pet at home

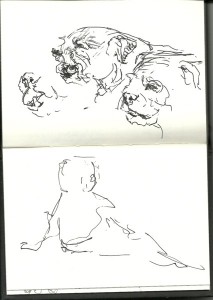

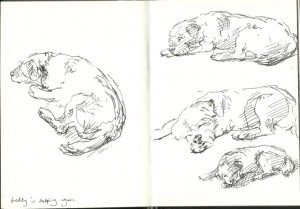

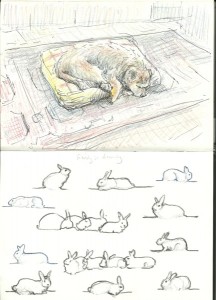

Today I shall share some of the dog drawings from my sketchbooks. This post is in memory of my Border Terrier, Freddy, who recently died at age 17 years.

Here are some suggestions for drawing pets, this time illustrated by sketches of my own dog. These tips are applicable to drawing any animal from life.

A variety of poses per page

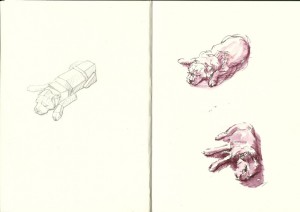

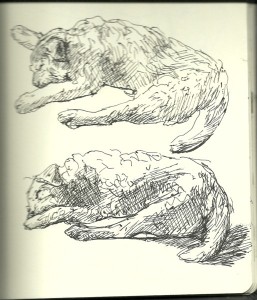

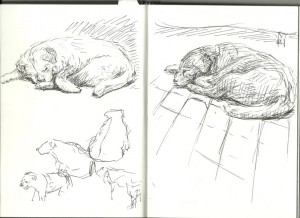

Pets make great models, but you never know when they will change position. Be prepared to start more than one drawing on a double-page spread of your sketchbook. It doesn’t matter if one or more of these poses remain unfinished.

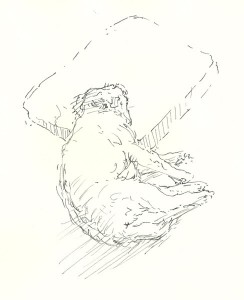

In the two sleeping poses above, I had time to build Freddy’s structure up with pen cross-hatching, and also to suggest his shaggy coat with pen strokes.

In the awake poses, below, I have used a more fluid style of line to suggest his posture without any attention to tone or texture.

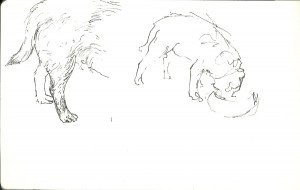

With a panting dog, consider what can and cannot be seen of the lips, teeth and tongue. In a shaggy Border terrier, the upper teeth and lips are obscured by hair, and we see a little of the lower canines (those are the long teeth) and tongue).

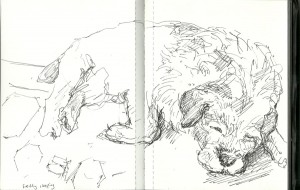

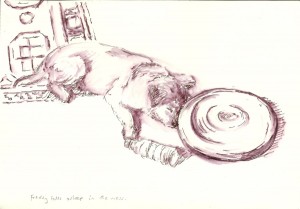

In the sketchbook below, I did a few scribbly drawings of Freddy moving about before he settled down for a sleep. The attempts to draw him in various fleeting postures adds a little character to the pictures of him sleeping.

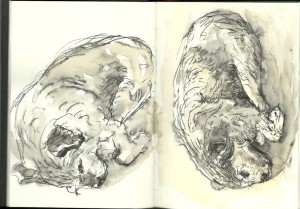

I made these two resting views into self-enclosed peaceful shapes, one on each opposite page.

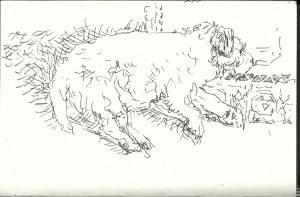

Here are three poses as seen almost from above as he changed sleeping position. He had long, shaggy fur over his back that parted in the midline. The shagginess could sometimes make it difficult to understand the actual structure of him and it is important not to fall into the trap of drawing every strand of hair. Sometimes the fur could be useful in my drawings, e.g. to help delineate where the middle of his back was positioned. Here I used the bulk of the fur to suggest his posture:

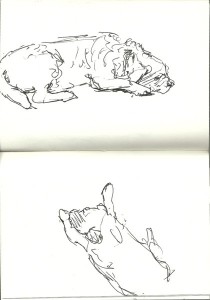

Sometimes I would embark on what I expected to be a longer drawing of him resting, only for him to move unexpectedly. This can be a blessing in disguise. See how most of these lines are left fluid and dynamic. The small amount of cross-hatching is restricted to one side of his head, and this is just enough to suggest which way the light is falling:

The brief sketch on the left page, below, merely hints at the terrier’s outline. He then moved position, but this was enough to give plenty of information about how he was sitting:

My pen drawings of Freddy were all made very directly, without any erasable under-drawing. Errors can be incorporated into the drawing. Indeed, multiple lines resulting from error can be beneficial, suggesting that the dog is moving or about to move.

What does your pet do?

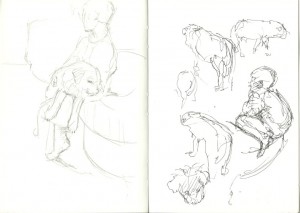

It is easiest to draw your dog as he or she sleeps, but do try to sketch your pet engaged in their usual day-to-day activity if at all possible. A good place to start is to draw them eating. You will hopefully have at least a minute or two to work:

If your pet tends to sit with a certain person, see if you can sketch them together. Freddy got on particularly well with my little boy, Oliver, who was forever picking him up. Here (on the left-hand page of the sketchbook, below) is Freddy draped comfortably over Oliver’s knee:

Does your dog lie in a funny position? In his old age, Freddy went through a phase of wanting to lie upside-down and would rest like that for a few minutes. This is a challenging pose to draw (watch out for all that foreshortening) and he tended to roll slowly back onto his side so I had to draw rapidly:

The dog in his environment

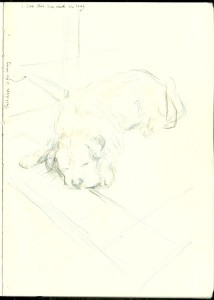

Do suggest bits of your pet’s surroundings in your pictures. Cats and dogs choose places where they tend to rest in the home. The way in which they sit or lie in these spaces is meaningful and worth recording.

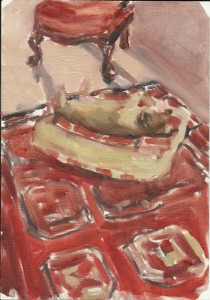

Here is Freddy towards the end of his life. By this stage, he was painful at times and wanted to lie with the left side of his head resting on his bed. He needed human help to get into this position but, once there, he would rest happily.

Here is Freddy surrounded by household mess that the children have left on the floor. He doesn’t mind. There is one of those soft wobbly balance cushions as well as a plastic water bottle. Being both blind and deaf, I think Freddy quite liked to be in contact with objects to give himself a point of reference:

Experimental approaches to drawing

Pets are completely uncritical of our efforts, do not insist that we flatter them, and they do not mind a bit if we try unconventional drawing methods.

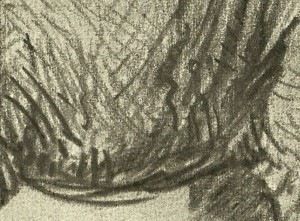

For example, here I used a chunky sticky of graphite to build up an image in cross-contour lines. These are lines that appear to curve over and around the form of Freddy and his bed.

This is a line drawing made with a Rotring pen, this time thinking of Freddy as more of a blank empty space and creating his image by building up short lines around him:

This drawing is layered with scribbly pen lines and ink wash. He emerges from the scribble on the page:

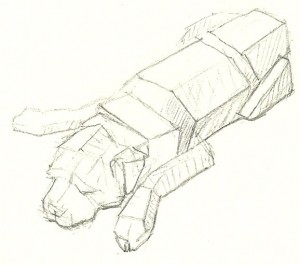

And here is the volume simplification drawing that I made of him just a few weeks ago:

A note about sketchbook layout

It is a good idea to change your drawing approach as often as possible within your sketchbook. This ensures that your sketchbook looks interesting to those who take a look through it. Different drawing methods also keep you on the ball as an artist, and ensure that you do not keep repeating the same picture over and again.

From time to time, you can even be a bit whimsical if you wish. In the double page spread, below, I drew Freddy sleeping yet again, but then imagined that he was dreaming of rabbits. He used to love to chase rabbits but never caught one:

The most obvious way to keep your sketchbook interesting is to work in a variety of media…

Remember to check this blog again on Sunday, as I shall be posting about sketching dogs in various media, from pen to pastel.

| Tags: blog, dogs, Freddy, sketchbook

Sketching in Hertford: The Memorial Stag

May 23, 2012

Sketching on location: the Hertford Memorial Stag

In summer, Hertford Art Society members meet outdoors to sketch and paint. Yesterday evening the weather was balmy, and we gathered in the Fore Street area of Hertford itself…

…before going for a drink at the Salisbury Arms.

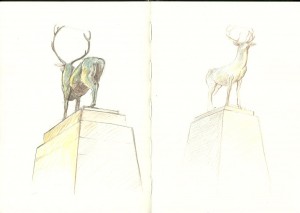

What really interested me most was the war memorial that stands in Parliament Square at the end of Fore Street. This is a tall stone plinth on which stands a magnificent bronze stag sculpted by Sir Edward Alfred Brisco Drury. This monument is surrounded by name panels commemorating those who died in World War I and World War II.

For more information about this memorial click this link:

http://www.roll-of-honour.com/Hertfordshire/Hertford.html

I sketched the stag from two positions. It is a challenge to draw an animal from below like this as foreshortening will be extreme. The first drawing was made with Durer and Inktense water-soluble pencils and a water-brush:

The second was drawn with coloured pencils without water.

Hertford Art Society is very active in the area and gives a warm welcome to new members. To see their full range of activities and exhibitions, follow this link:

http://hertfordartsociety.co.uk/

| Tags: sketchbook

Oil sketches of Freddy

May 19, 2012

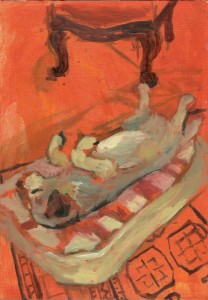

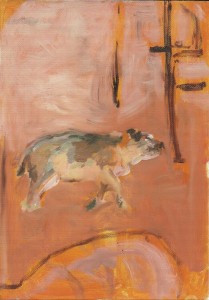

In this post I share some oil sketches that I made of my old terrier…

This post is in memory of my dear border terrier, Freddy, who died at the beginning of this month.

Over two weeks have passed since the end of his life and, though I felt devastated to start with, I can now start to think again of funny stories about him even if just in a wistful way. For example, there was the time that he ate through someone’s leather rucksack in order to reach their sandwiches. And on another occasion he went missing and was eventually found trapped (quite happily) inside the lidded compost bin which he had thought was a suitable lunch venue.

There is no shortage of pictures of this little character. My sketchbooks are full of them, and he obligingly posed at drawing classes towards the end of his life.

The decision to sketch in paint

He had been ambling about as a blind and deaf dog for a year or so, but was then ill in February 2012 and I was not sure at the time whether or not he would pull through. I managed to get him comfortable again through a combination of electrolytes, home-cooking and medications. It must have been a sense of panic at Freddy’s rapid aging that got me to bring my easel downstairs, protect the furniture with sheets, and get down to some oil sketches of him from life.

The process of painting Freddy made me feel a bit better about his ageing process. It forced me to observe him closely as he rested, and it was clear that he absolutely relished relaxing and could be happy and comfortable in various positions, whether curled on the floor or (a February 2012 favourite) upside-down on his bed.

Pictures and memories

I never quite knew when Freddy would move as I painted him, and the immediacy of working from life brought an emotional directness to these pictures. These little paintings are all technically flawed, but those that I have included in this post are more successful than a photo in that they are closer to my personal memory of him.

Have you seen David Hockney’s oil sketches of his dachsunds? Check out this charming book which is full of Hockney’s paintings of his dogs, Stanley and Boogie. This was an inspiration to me. Much of the point of these pictures is the portrayal of dogs in their environment, just fitting into the space and with one another. http://www.amazon.co.uk/David-Hockneys-Dog-Days-Hockney/dp/0500238340

I am currently sorting through a great pile of old sketchbooks, looking for pictures of Freddy. Remember to check back here on Thursday as my next post will focus on my sketchbook dog drawings.

Comments (4) | Tags: blog, Freddy, oils

Yesterday’s equestrian life drawing session

May 14, 2012

Photos and a short report from the 13 May 2012 horse life drawing day

Thanks to the people and animals who made this all possible

Yesterday’s equestrian life drawing session was a great success. The setting was lovely, the horse behaved beautifully and the sun even shone. We are extremely grateful to Polo the horse, Martin who owns the farm and who made the day possible for us, and to his daughter Lily who held Polo still and who even performed some inspiring horseback gymnastics.

As you can see from the photos, Polo was perfect to draw, having well-defined muscle structure. I know how difficult it is to get such a horse to look white. Lily certainly went to great trouble to get Polo looking splendid for us.

The set-up for the day, and some inspiring Old Master drawings

Ten artists set up easels around Polo, our model. Working in a variety of media including charcoal, chalk, watercolour, Neocolour wax pastels and graphite, they drew the horse from differ ent angles.

ent angles.

After warm-up exercises using continuous line drawing, I suggested working tonally and really looking at the clearly-defined planes and masses on this horse. In her conformation, she does remind me of the horse in Ruben’s “Rear View” study (right).

Though she kept her forelimbs very still, Polo had to shift the weight from one hindlimb to the other every ten minutes or so. The best trick seemed to be to have two pictures on the go at once, one with her resting her left hind and the other with her resting her right hind leg. It was then possible to move from one picture to the other when the weight shifted.

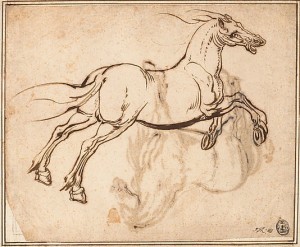

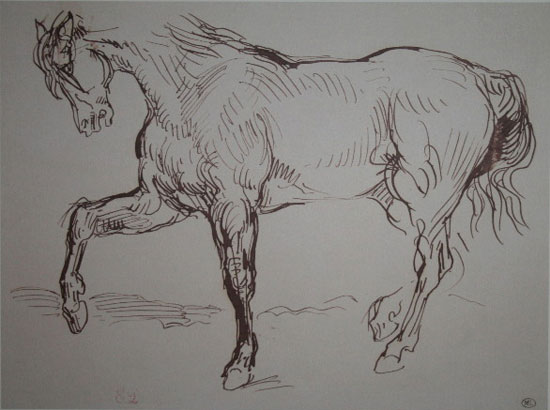

I then suggested a more energetic and broad way of working, in which every mark was to respond directly and decisively to the horse. This drawing by Delacroix was one of those suggested as inspiration:

And also this one (you can tell that I am a big fan of Delacroix’s drawings):

A surpise acrobat!

Lily, who had been patiently holding the horse for us all morning, couldn’t resist changing into her vaulting gear and jumping on. She is a very experienced and successful equestrian vaulter and held these positions absolutely still.

It was a rare and unexpected treat for the group to have the chance to draw an acrobat balancing on a horse! Lily was able to hold horseback poses beautifully for several minutes at a time.

Considering how to draw figures balanced on top of one another

The main focus had to be the points of balance of horse-rider on the horse. Polo had to be shown as convincingly 3-dimensional and able to support the girl’s weight. For the artist this is quite a challenge. I had this very direct drawing by George Jones in my file as an example of a figure balanced on a horse:

A tour of the farm

At the end of the day, Martin gave us a tour of the farm, walking us through fields of glossy cattle, past pollarded woodland and land set aside to encourage wildlife. He was proud to point out mixed-species hedges that he had planted, and talked to us about the numerous birds and wild-flowers that thrive on this land.

Next month’s equestrian life drawing class

All in all this was a very interesting and successful day. I have another horse life drawing workshop planned for Sunday June 17 (same venue). Click on “Contact”, above, to book your place.

| Tags: blog, equestrian life drawing, horses

Equestrian life drawing, Sunday June 17

May 14, 2012

Time: 10am-3pm

Venue: Standon Green End Farm, nr. Ware, Herts, UK

Cost: £25 if you bring your own easel and backing board, £30 if you need me to bring an easel for you. I shall provide drawing materials for everyone including paper, charcoal, chalk and graphite.

You need to bring: Clothing suitable for the weather, farm-friendly footwear, your own picnic lunch, easel, bulldog clips (or similar) and A2 backing board if you have them.

This session is set up much like a tutored human life-drawing session with artists working at easels around a posed model. In this case the model is a horse. We hope to use Polo (the white horse shown above) again, as she is excellent at standing still and has very defined muscle structure.

If weather is wet then we shall work in a covered barn.

If conditions allow, we may have another chance to draw Lily posing on this horse. She is a trained equestrian vaulter and it was very exciting to be able to draw her balancing on Polo during our horse drawing day in May.

This is a working farm with other animals including sheep, cattle and pigs as well as very attractive areas of land managed for wildlife. Artists will have the option of spending some time drawing elsewhere on the farm during the day.

Places are limited, so please get in touch with me to reserve your space (Click on “Contact” at the top of the page).

Comments (2) | Tags: equestrian life drawing, workshops

Thoughts on horse anatomy: The hindlimbs

May 12, 2012

Some thoughts on horse hind limbs with reference to Great Master drawings

Above: Jacques Callot (1592-1635) “Study of a Horse”, quill and reed pen and iron gall ink, 23.5×28.6cm

Basic structure of the hindlimbs

The hindlimbs have the kick and thrust to propel the horse forward. Much of the muscle bulk is up high in the rump (see my post from 9th May 2012, “More lovely horse anatomy”). The lower parts of the hind legs are made up mostly of bone and tendon.

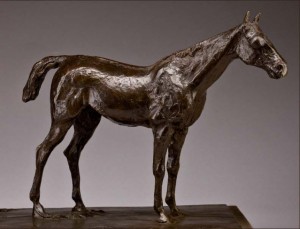

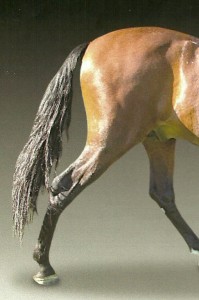

Below I have labelled an equestrian sculpture by Edgar Degas to show the positions of two major joints, the hock and fetlock, and the bone between them which horse-people call the cannon bone:

Right and left: Edgar Degas. The original wax for this bronze cast was modelled around 1881-82.

Angle of cannon bone compared to the ground

See how bent the leg is at the hock in the standing horse. At rest, the horse puts most of his weight on vertical front legs while the hindlimbs have more freedom to be placed further forward or back. The cannon bone of the hindlimb is rarely vertical as seen from the side.

An image of a galloping horse

Just for fun, here is an image of a galloping horse showing something of bone structure and limb flexibility:

The Achilles tendon

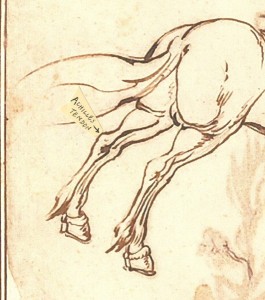

From the rear, the shape of the Achilles tendon at the back of the hock joint is clearly visible. The combined tendons of several muscles (the superficial digital flexor, biceps femoris, gastrocnemius and semitendinosis) run down the back of the leg as a tense band, the Achilles tendon. Part of this attaches to the bony point at the back of the hock. Part continues over the hock and as a long tendinous band down the back of the lower leg (the superficial digital flexor tendon). Here is a detail of a 17th century quill and reeed pen and ink drawing by Jacques Callot featuring the Achilles tendon (the full picture is shown at the top of this post):

Above: detail from Jacques Callot (1592-1635) “Study of a Horse”, quill and reed pen and iron gall ink, 23.5×28.6cm

Volumes and planes around the hock joint

Tendons around the hock joint appear as clear-cut structures with well-defined edges because they are under tension. They form a wedge-like shape above the hock, and the different tones on the planes of this structure can be used to best advantage when drawing the horse.

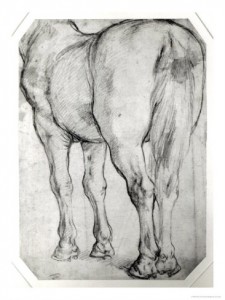

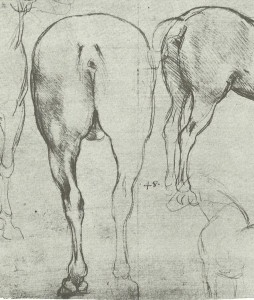

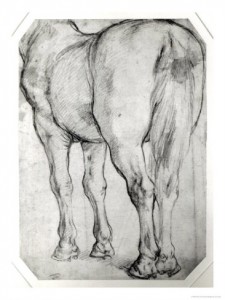

To illustrate this, I have included a drawing by Peter Paul Rubens showing the rear view of the horse with great structural clarity. See how the light hits the triangular top surface of the tendon, creating an interesting shape within the picture:

Above: Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640) “Horse’s rear”, pencil on paper

Tonal modelling of the hock region

By changing the lighting, the structures of the hock can form further interesting shapes of light and shade:

Above: Photo of horse’s hindquarters under strong directional lighting. Notice the interesting shapes of light and dark tone around the right hock joint.

How the Achilles tendon connects to the rest of the leg

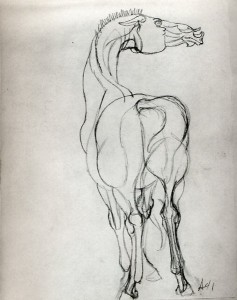

The Achilles tendon is not isolated, but runs up to the muscles high in the rump, and is also continuous with tendons running down the back of the lower leg down towards the foot. Leonardo da Vinci showed in a lovely fluid way how the tendon runs from muscle, over the hock and down the back of the leg in this study, one of those for the Sforza monument:

Above: Leonardo da Vinci “Studies of a horse” c. 1490

Appearance of muscles when legs are carrying more weight

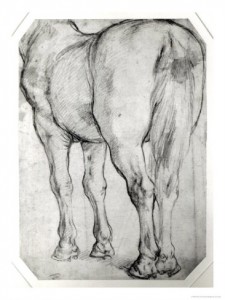

Here is another horse study by Leonardo da Vinci, this time in red chalk. He has focused on how those tendons run towards the muscles. In this drawing, bulges in tendons and muscles are thought of as rounded structures rather than the more angular shapes portrayed by Rubens in his “Rear view of a horse”, above. See how those muscles bulge when the horse takes full weight on the hind legs:

Above: Leonardo da Vinci “Study of horses”, red chalk on paper, 1504-6

An unsettling picture by Agostini

In the image below, muscles bulge as emphatic rounded forms. The effect is one of unsettling tension, with taut tendon lines running up the back of the legs to those tight muscles.

Above: Peter Angostini (1913-1993) “Horse”, graphite

Rounded and angular compositional shapes within the hindlegs

Finally, here are two proud and prancing horses. Though the handsome heads are the main focus of the picture, the contrast between the rounded rump of the near horse and the angular bent leg beneath it gives the image much of its energy. Try covering the rear end of the horse with a piece of paper, then look at what remains of the picture, and see how this takes the oomph out of the image.

Above: Two Horses Attributed to Allegrini, pen and brown ink, 11.7×11.7cm, 1624-63

| Tags: anatomy, horses

More lovely horse anatomy: The rear view

May 9, 2012

Tips on drawing the back end of the horse, with reference to paintings by Great Masters

If, when drawing a horse, you find yourself positioned behind it, you have not drawn a short straw. The rear of the horse is full of design possibilities. You have the great masses of muscle ready to propel the animal forward and, below, the structure of the bones and tendons of the back legs is easily visible even in a thick-set horse.

Look at these powerful compositions, “The Rear View” by Peter. P. Rubens ( below) , and “Horse Market, Five Horses at the Stake” by Theodore Gericault (above).

Let’s first consider how to draw the muscular rump of the horse. The muscles of the rear end drape over the bones of the pelvis. This gives the rump a recognisable shape with left and right sides mirroring one another.

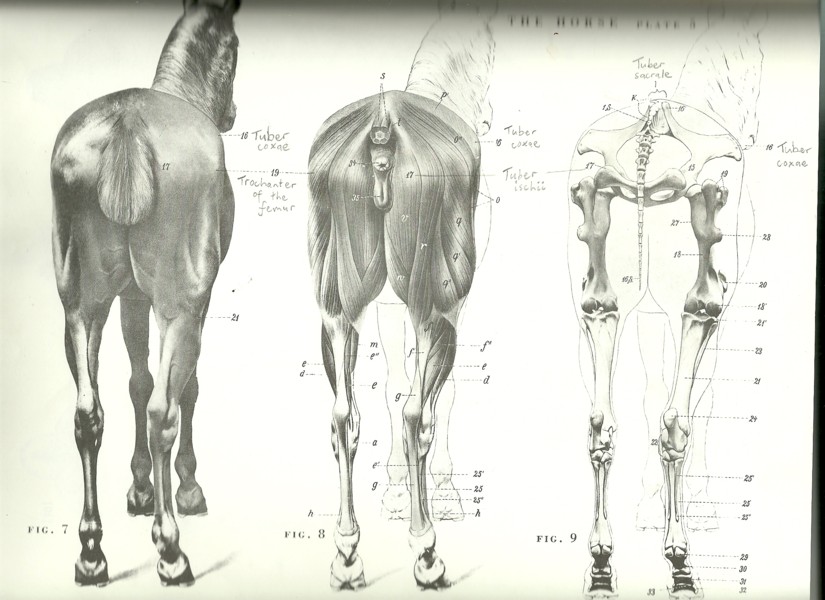

Diagram from “An Atlas of Animal Anatomy for Artists”

My favourite anatomy book is “An Atlas of Animal Anatomy for Artists” by W.Ellenberger, H.Dittrich and H.Baum. I have the 2nd edition which was published in 1956. It covers the horse, dog, cow and lion, with a few oddities in the appendix. I just wish that I had come across this book years ago when studying veterinary medicine as I find these diagrams more pleasing to look at, clearer and easier to relate to living animals than the standard vet anatomy diagrams (and the lion would have been a good distraction). Here is one plate from this book (the pencil scrawl is my own):

The above drawings show three representations of the rear view of the horse. On the right hand side is the bony skeleton. The middle drawing shows how the muscles fit over the bones. On the left we see the rear of the horse complete with skin. Even in this drawing, it is possible to appreciate the direction and shape of the muscles, and to see how these are attached to or stretched over prominent bones.

Deciding where the horse’s midline is positioned

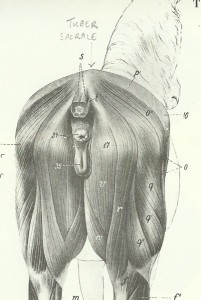

In drawing the horse from the rear end, the first thing to be aware of is where the midline is positioned. Some horses have a coat marking (a “dorsal stripe”) over the spine leading back to the tail, as if just to help artists:

If not, then you just have to imagine a line in this position. The two sides of the rump should be symmetrical on either side of this line which means, from almost every viewpoint, the artist needs to take special care with foreshortening.

Considering the overall shape of the rump

Although the silhouette of the rump is curved from every viewpoint, it cannot really be simplified down to a sphere or into two hemispheres. The rump is taller than it is wide, and rather slab-sided. It helps to be aware of the most prominent “landmarks”:

The highest point is the tuber sacrale:

I have marked this high point (the tuber sacrale) on the diagram on the left. If you scroll up to the diagram of the 3 horse rear views, you will see it also marked on the skeleton quite far forward where the pelvis attaches to the spine.

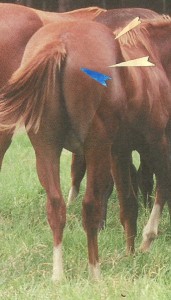

In the photo on the right, I have marked the position of the tuber sacrale with a cream arrowhead. See how the rump slopes down from here back to the base of the tail.

Widest points of the rump

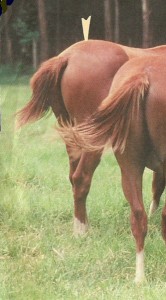

On each side of the horse’s rear, two wide points are the tuber coxae (further forward) and the greater trochanter of the femur (further back). In the photo below, I have used cream arrowheads to mark the positions of the greater trochanters of the femur. This trochanter is simply a knobbly bump on the outside surface of the thigh bone.

Position of greater trochanter and tuber coxa marked on a photo

In the photo, below, I’ve marked the greater trochanter again with a cream arrowhead and, above this in the photo, I’ve marked the tuber coxa with another arrowhead.

From some angles, it can help to think of an imaginary line running from the tuber coxa and angling slightly down and back to the greater trochanter. This imagined line marks a change of plane over the horse’s rump.

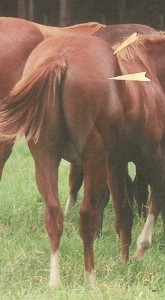

The point furthest back on each side is the tuber ischium

In the next photo, I’ve highlighted the final “landmark” with a blue arrowhead. This is the tuber ischium. There is one of these on either side of the tail, and they just out at the back of the pelvis. These three “landmarks” define the edge of a slab-like surface at the top of the rump.

Planes resulting in tonal change over the rump

Now take a look at the same photo without the arrowheads and see how the sunlight reaches the slab-like top of the rump in a patch bounded by those three landmarks:

Planar modelling and design possibilities

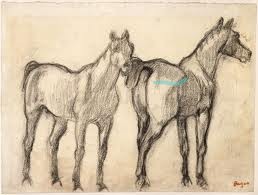

This change of plane over the rump has been exploited by artists for its design possibilities. Here is a drawing by Degas (Two Standing Horses, below left) showing the intriguing change in appearance of the rump when seen from different angles. On the right, I have shown the picture again, having marked an approximate line from the tuber ischii to the greater trochanter to the tuber coxa, so that you can see how this fits in with Degas’ strong planar modelling of the horse:

In Gericault’s “Horse Market: Five Horses at the Stake”, below, we see again how the anatomy of the rump has been emphasised. The bony landmarks are quite obvious in the right-hand horse, in which they create an illuminated oblong that is important within the composition.

The slight hollow down the side of the thigh

Under the tuber coxa to greater trochanter line, there is a slight concave valley down the side of the thigh. Take a look at this rear view drawing by Leonardo da Vinci, one of his preparatory drawings for the Sforza monument. The edges of the rump are shown by a series of elegant curves. My light pink arrowhead points to the concave “valley” down the side of the thigh.

Those of you who come along to the equestrian life drawing day on Sunday should have the chance to lay your hands on the horse and feel where the important bones are positioned, which sections are concave and which are convex. This will help you to understand the structure of what you are seeing.

Don’t forget to check back here on Saturday as I shall post some thoughts on drawing the lower parts of the hind limbs.

| Tags: anatomy, horses

Equestrian life drawing May 13

May 7, 2012

Sunday 13 May 10am-3pm: “Equestrian Life Drawing”

**One place has just opened up. Please get in touch if you’d like to come**

This day is planned much like a day of tutored life drawing in the studio, except that we have horses to work from instead of humans and shall be on a farm. Handlers will do their best to keep the horses still for us. We shall work outdoors if weather is fine, or in a large covered barn if wet.

Venue: Standon Green Farm, nr. Ware, Herts

Basic materials are provided (paper, charcoal, chalk, some graphite and other bits) though you are welcome to bring your own.

Cost: £25 if you bring your own easel, or £30 if you need me to bring an easel

| Tags: equestrian life drawing, workshops

The volume simplification class, and my last ever drawings of Freddy

May 5, 2012

What is volume simplification?

Yesterday I discussed volume simplification with the class. The idea of this is that complex figures can be represented as a set of simple geometric shapes either as an exercise or on the route towards abstraction. It is well worth trying with human and animal figures, as it forces the artist to ignore distracting surface details and to focus on the most important facts about the body, namely the positions of all its main parts.

Representing each part of the body by a simple 3D shape

At its most basic, the body can be thought of as being made up of several units (head, shoulder girdle, chest/belly, hips, etc.) and each of these sections can be represented by a geometric volume such as a cuboid, wedge or cylinder. It is important to show how each “unit” is tipped or angled. For example, people often stand with their shoulders tipped one way and their hips tipped in the opposite direction.

A dog drawn as simplified volumes

To illustrate this way of thinking, here is a recent double page from my sketchbook. These sketches are the very last that I made of my dear old terrier, Freddy. He unfortunately had to be put to sleep on Wednesday and is very sorely missed. At some point soon I shall put happier pictures of him onto this website.

| Tags: Freddy, sketchbook

Edges: last Friday’s class and, in particular, some thoughts on combining edges and cross contour lines

May 2, 2012

Last Friday’s “What to do about edges” class

It turns out that there is no single best approach for drawing edges, rather many possible ways of working. In the class, each artist took a picture by a “great master”, from Leonardo da Vinci to Henry Moore, discussed how edges had been tackled in that picture, and attempted to apply these methods to still life drawing.

This meant that people attending the workshop drew in completely different ways from one another, and several media were used from red chalk to ink line and wash.

I had come up with a long list of possible edge strategies. There was plenty to discuss at the workshop, lengthy notes to take home, and I have probably only scratched the surface of this subject.

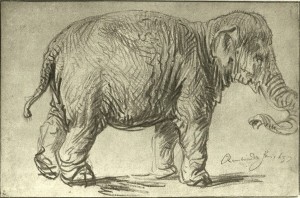

Looking at how Rembrandt used edges in one of his elephant drawings

Out of the great master drawings that we analysed, one of my favourites is Rembrandt’s black chalk drawing entitled “An Elephant”, from 1637. This is in my rather battered but beloved copy of “Rembrandt as a Draughtsman” by Otto Benesch, which I had bought from a library sale for the measly sum of 30p. The orginal drawing is 233 x 356mm.

This elephant study is remarkable in that it shows the bulk, roundness, and shifting weight of the massive creature completely convincingly, while not attempting to create a total illusion of reality.

A close look at a soft slipper to further our understanding of edges and cross-contour lines

Rembrandt achieved these effects by the seamless combination of edges and cross-contour lines. To show the point of this, I have photographed my slipper, which has soft rounded curves like the elephant:

The red arrow points to the outer edge of the slipper (some artists use the term contour to describe the outer edge). As the opening of the slipper curves inwards, the light falls on some surfaces more than others, creating internal edges (“lines” of tonal contrast). I have marked two of these with blue arrows. Well, we could argue whether or not to call them edges, as their appearance is dependent on how the light falls, and indeed they merge into the curved surface of the slipper. If I were sketching the slipper in pen, I might be tempted to indicate some of these internal edges by using lines.

The inside of the soft slipper, with various curves merging into one another, can be seen as similar to the rounded elephant. One of Rembrandt’s aims in drawing the elephant was to show how curved or rounded its body was. For example, its belly is not a sphere, but is rounder low down and further back (due to the great weight of its contents) and relatively flat high up where it drapes over the spine.

Rembrandt achieved this by combining outer edge lines with cross-contour lines. The latter are lines that appear to curve around the surface of the elephant. Look at these cross-contour lines around the elephant’s trunk. I have marked them with purple arrows.

There is some kind of edge line (made up of many gestural marks) all around this elephant. In some places these outer edge lines are very heavy, to suggest parts of the body in shadow, but also to emphasise the weight of the elephant hanging down. The underside of the animal’s belly is represented by weighty charcoal edge lines which merge into heavy cross-contour lines.

On the other hand, the edge lines over the elephant’s back are light and floaty as this is where the light is falling:

Now see how Rembrandt handled the stomping back feet of the animal. There are curved, tapered charcoal marks (I’ve marked them with orange lines) here that suggest an outer edge leading into a cross-contour line but also somehow suggest the energetic lift and stomp of the feet. I would perhaps not have quite enough information from this sketch with which to sculpt the hind feet of this creature but, in a few charcoal marks, Rembrandt has hinted at their roundness, weight and movement.

Now see how Rembrandt handled the stomping back feet of the animal. There are curved, tapered charcoal marks (I’ve marked them with orange lines) here that suggest an outer edge leading into a cross-contour line but also somehow suggest the energetic lift and stomp of the feet. I would perhaps not have quite enough information from this sketch with which to sculpt the hind feet of this creature but, in a few charcoal marks, Rembrandt has hinted at their roundness, weight and movement.

Look at the information Rembrandt gives us about the tail. He combined edge lines and cross contour lines to suggest that it is not plump, but is wrinkled, creased and rather knobbly.

There are even little hairs suggested on the top of the elephant’s head and on the end of its tail.

Rembrandt’s elephant drawing tells me what it might be like to stand next to, and to touch, the real animal. This is not a photo-realistic image but, in a few varied charcoal marks, Rembrandt has given me more information than a photograph.

![[title not known] null by George Jones 1786-1869](https://art2art.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/George_Jones_19th_century_Horse_Drawing_Untitled_Tate_Britain-300x200.jpg)